Single Malt Scotch for Feminists

Image by iStock

The Men’s Section: Orthodox Jewish Men in an Egalitarian World

By Elana Maryles Sztokman

University Press of New England, 288 pages, $85

A few years ago, a friend announced that he intended to start a “Kiddush club” at our synagogue. “Our shul needs more of a social scene,” he declared, “and some high-quality single malt whisky!” he added jokingly. I was vehemently opposed. Our synagogue is a “partnership minyan,” which seeks to maximize women’s participation in the prayer service within the bounds of Halacha and the Orthodox community. A Kiddush club smacked to me of a classic patriarchal construction, a complete contradiction of our attempt at re-aligning the gender dynamic of Orthodox synagogue life.

I was thinking of this exchange as I was reading Elana Sztokman’s new book, “The Men’s Section: Orthodox Jewish Men in an Egalitarian World,” an ethnography of men in partnership minyanim. Sztokman asks a fascinating question: What do the men get from it?

As Sztokman describes at the beginning of the book, the partnership minyan phenomenon started in 2001 with two small minyanim in Jerusalem (Shira Chadasha) and New York (Darkhei Noam). Those two are now regularly attended by hundreds every Shabbat and have prompted 25 other such minyanim in places as far flung as Melbourne and Beersheva and as traditional as Skokie, Ill., and Englewood, N.J. At these minyanim, women and men share equally in Torah reading and speaking before the community, and women lead some parts of the service — but men and women are separated by a mechitzah, the barrier between the genders that is the hallmark of an Orthodox synagogue. While still considered anomalous in the eyes of most of the Orthodox community, partnership minyanim are no longer beyond the pale.

Much has been written about the experiences and needs of Jewish women that led to the creation of these synagogues, but little about the men who attend them. Why do they attend, and what can their experience teach us about being Orthodox or about being a man?

Sztokman’s question is critical far beyond the boundaries of the Orthodox community. As she puts it: “…most women today are able to easily say, ‘I was brought up to believe that to be a woman means one thing, but I have decided that to be a woman means something else entirely.’ Men, for the most part, do not have a language to describe how they were socialized into masculinity.”

Having grown up male in the liberal Orthodox community and been an active member in partnership minyanim on three continents, it was jarring to read about myself as an anthropological phenomenon, discovering how I was “socialized into masculinity.” But this is exactly Sztokman’s goal: to give language to men about the construct of their gendered — and religious — identity.

In the first, and best, part of the book, Sztokman uses the work of sociologist Paul Kivel, who describes masculine socialization as creating an “act like a man” box. Based on her interviews, Sztokman offers a “Be an Orthodox Man Box,” whose characteristics include being “committed, serious, tefillin-wearing, learned, cerebral” to the exclusion of “inconsistent, weird, single, unlearned, light-weight.” In Kivel’s theory, the box’s categories keep men in line with the desired gender identity. The men Sztokman interviews described how, in the Orthodox world, gender categories keep you on the religious straight and narrow — inconsistency in your halachic practice means you are not a “real man.”

In the second part of the book, Sztokman asks men what makes them “abdicate their rights” and attend partnership synagogues, expecting to find a group of male feminists. To her surprise, she discovers that “men come to the partnership synagogue for a whole host of reasons, the overwhelming majority of which have nothing to do with feminism.” This finding is in line with a well-known fact of synagogue membership: People don’t join synagogues on the basis of ideology or denomination as much as out of an existential need for community and a desire to be “seen.”

Sztokman’s research is at times deeply insightful and at times heavy-handed. She is caught in the assumptions of second-wave feminism and would benefit from the use of new theories of agency, such as explanations by Talal Asad and Saba Mahmoud of how people construct empowered identities within traditional structures. And yet, the book remains a vital contribution well beyond the scene of liberal Orthodoxy.

Understanding the confluence of gender identity and Jewish identity is key to creating vibrant Jewish communities — and it cannot simply be set aside in the name of a gender-blind egalitarianism. To the liberal movements, for whom a “man drain” has become the latest cause for concern, this book might give some useful insights into how to create the kind of communal experiences that both use gender identity (like the Kiddush club) and reconstruct them.

Reconstructing gender identity is key to a question that Sztokman’s book discusses only tangentially, but one that is crucial: As minyanim grow into true communities, they are challenged to create more meaningful leadership structures. Many of the partnership minyanim are characterized by an anti-clericalism that is in keeping with the feminist challenge to traditional male authority. Instead of centralized (and traditionally male) leadership, they strive to create a broad lay leadership. But — though Sztokman cannot bring herself to say it — these communities must find some new model of the rabbinate, beyond the masculine model, that offers communal services but does not wield patriarchal authority. This is not simply a question of ordaining women but about creating a new set of gendered expectations from leadership and members.

As Sztokman’s book shows, while feminism might be the driving force of the partnership initiative, the key to its popularity is the sense of belonging that comes from the Kiddush clubs, the pastoral support, the children’s services and the shmoozing that makes people want to stay connected. Some of those institutions might indeed need to continue to work in the ways the “men’s clubs” of old used to work, creating and strengthening this or that “box,” though working within new paradigms. Sztokman’s book provides the intellectual tools through which we can reconstruct traditional gender identity in novel ways. I can now sip single malt during haftorah with a renewed sense of purpose.

Rabbi Mishael Zion is co-director of the Bronfman Youth Fellowships and the author of “A Night to Remember: The Haggadah of Contemporary Voices” (ZHP, 2007).

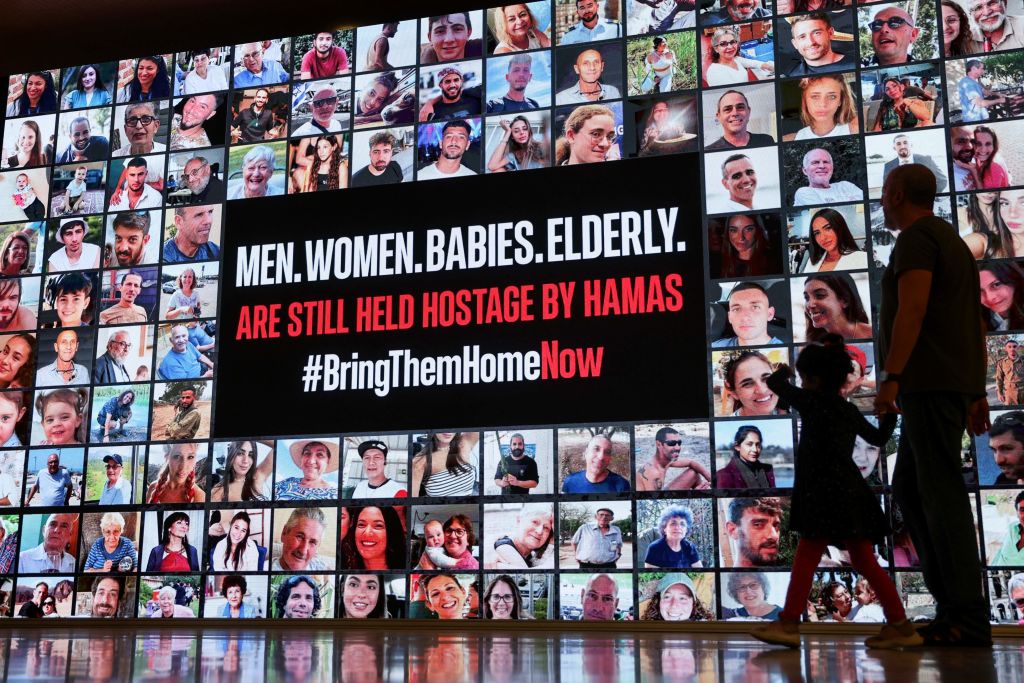

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning journalism this Passover.

In this age of misinformation, our work is needed like never before. We report on the news that matters most to American Jews, driven by truth, not ideology.

At a time when newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall. That means for the first time in our 126-year history, Forward journalism is free to everyone, everywhere. With an ongoing war, rising antisemitism, and a flood of disinformation that may affect the upcoming election, we believe that free and open access to Jewish journalism is imperative.

Readers like you make it all possible. Right now, we’re in the middle of our Passover Pledge Drive and we still need 300 people to step up and make a gift to sustain our trustworthy, independent journalism.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Join our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Only 300 more gifts needed by April 30