Movement With Purpose

Image by Jesse Untracht Oakner; courtesy of the new museum

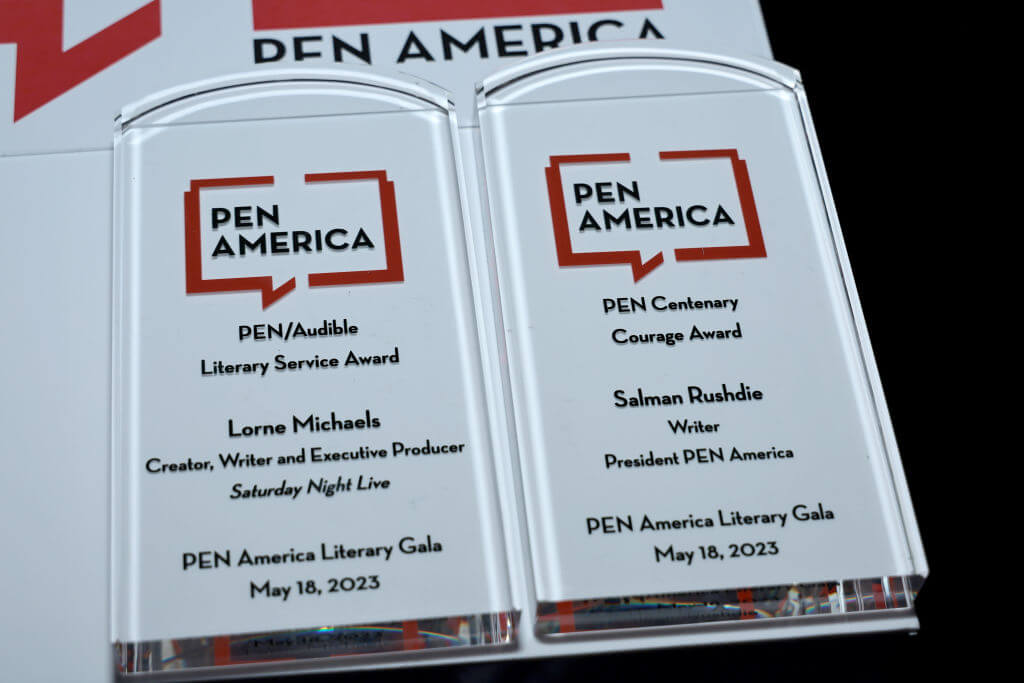

Dividing the Union: Public Movement performs its short event at Washington Square Park in New York. By separating pedestrians they promoted dialogue. Image by Jesse Untracht Oakner; courtesy of the new museum

Hard on the heels of Israel’s summer protests for social justice, Dana Yahalomi, leader of the “performative research” group Public Movement, arrived in New York City, only to find the Occupy Wall Street movement camped in Zuccotti Square. Coming from the largest protests in her country’s history and being met with what is now a worldwide movement, the situation might have appeared to Yahalomi somewhat surreal.

Yahalomi had been invited by The New Museum, in New York, and by the contemporary Israeli art fund Artis, to take up a six-month residency in 2011 that would allow her to participate in the visual art performance biennial Performa 11. Her residency continues until April, and it also covers the museum’s second triennial, “The Ungovernables,” opening on February 15.

Public Movement was founded in 2006 in Tel Aviv by Yahalomi and Omer Krieger, who led it together until August 2011, when Yahalomi assumed sole leadership. According to its website, the group views itself as a “performative research body that investigates and stages political actions in public spaces,” establishing a dialogue, at times a literal one, between art and politics. By re-enacting and performing ceremonies, rituals, folk dances and variations thereof, the group presents carefully choreographed “actions” in open public spaces, often performed in collaboration with public teams such as the police or the medical services.

Israeli society accords the army a high cultural valence. This is reflected by Yahalomi’s group, which functions with the appearance of a well-organized unit: Its performances are characterized by its members moving in group formations, attired in white uniforms and sporting a symbolic flag. Rooted in the ideology of modernist art movements such as the constructivists, and resonant with echoes of early 20th-century European folk movements, the performances, often dark, can also evoke a bittersweet nostalgia for the Old Country.

During the course of her residency, Yahalomi will be hosting five biweekly salons, engaging in debate and discussion with the local community and a host of academics and activists. Speaking with the Forward about the members of her public movement group, Yahalomi said that “we see ourselves as social scientists. When we are invited to work in a new city, we learn the local context, the politics and the history, and we ask ourselves what is to be done.”

Each salon will have a specific focus. Yahalomi intends to broach the subjects of the role played by Taglit-Birthright Israel in the American Jewish community and to examine the status of New York’s Muslim community and the Palestinian right of return. According to Yahalomi, “We will examine the mechanisms behind Birthright Israel, how it is constructed, what has made it one of the most successful programs for the Diaspora community, and consider the appropriation of such strategies toward the potential creation of a Birthright Palestine.”

The salons might or might not produce a final action; that will be determined by the outcome of a vote by the general public on the idea of a “Birthright Palestine.” A positive vote will result in an action.

Yahalomi’s interest in Birthright grew from an action that Public Movement mounted with young Americans Jews in Israel, “Where To?,” which took place in 2011 in Holon, at the Israeli Center for Digital Art. Public Movement invited young Jews from the Birthright groups to discuss such questions as “What does it mean to be proud to be Jewish?” “Do they support a Palestinian state?” and “Do they think all Jews should live in Israel?” Yahalomi recalls that “they were very passionate, and it was an amazing encounter for us.”

Yahalomi is a woman with a sense of purpose. The surge of street protests in Israel and New York has seen her lead the group toward a more activist approach. Over the course of the summer in Israel, Public Movement staged a series of folk dances with the community at major intersections in Tel Aviv. More recently, Yahalomi joined with Occupy at Zuccotti Park to enlist the public to participate in an oft-performed work, “Positions.” The work is a “choreographed demonstration” that has been performed in Israel and several European countries. Its execution is dependent on what the group members think is required in each country, vis-a-vis the social and political context and the public’s “positions” within said context.

As part of their triennial, the New Museum had obtained a November 6 permit for Yahalomi to stage a public performance for four hours at Washington Square Park. Yahalomi, realizing that the work would take only a half-hour to perform, handed over to Occupy the remaining time to engage the public in the issues of the day, and then proceeded to converse with a member of the New York City Police Department on just where the dividing line is between art and politics. The police officer was not convinced that what he was witnessing lay in the artistic domain.

For all the rhetoric generated by Yahalomi and Public Movement, the group is essentially about “action” or, in its leader’s words, “making politics.” Yahalomi explained: “Politics happens with bodies; you perform with your body certain statements. The mere presence of your body in a certain place is a performance of politics.” The group has performed in various countries in Europe, but this residency has resulted in Public Movement’s first encounter with America. Whether it can move the American public remains to be seen.

Graham Lawson is a freelance journalist based in Tel Aviv.

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning journalism this Passover.

In this age of misinformation, our work is needed like never before. We report on the news that matters most to American Jews, driven by truth, not ideology.

At a time when newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall. That means for the first time in our 126-year history, Forward journalism is free to everyone, everywhere. With an ongoing war, rising antisemitism, and a flood of disinformation that may affect the upcoming election, we believe that free and open access to Jewish journalism is imperative.

Readers like you make it all possible. Right now, we’re in the middle of our Passover Pledge Drive and we need 500 people to step up and make a gift to sustain our trustworthy, independent journalism.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Join our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Our Goal: 500 gifts during our Passover Pledge Drive!