Lyrical Voices of Zion

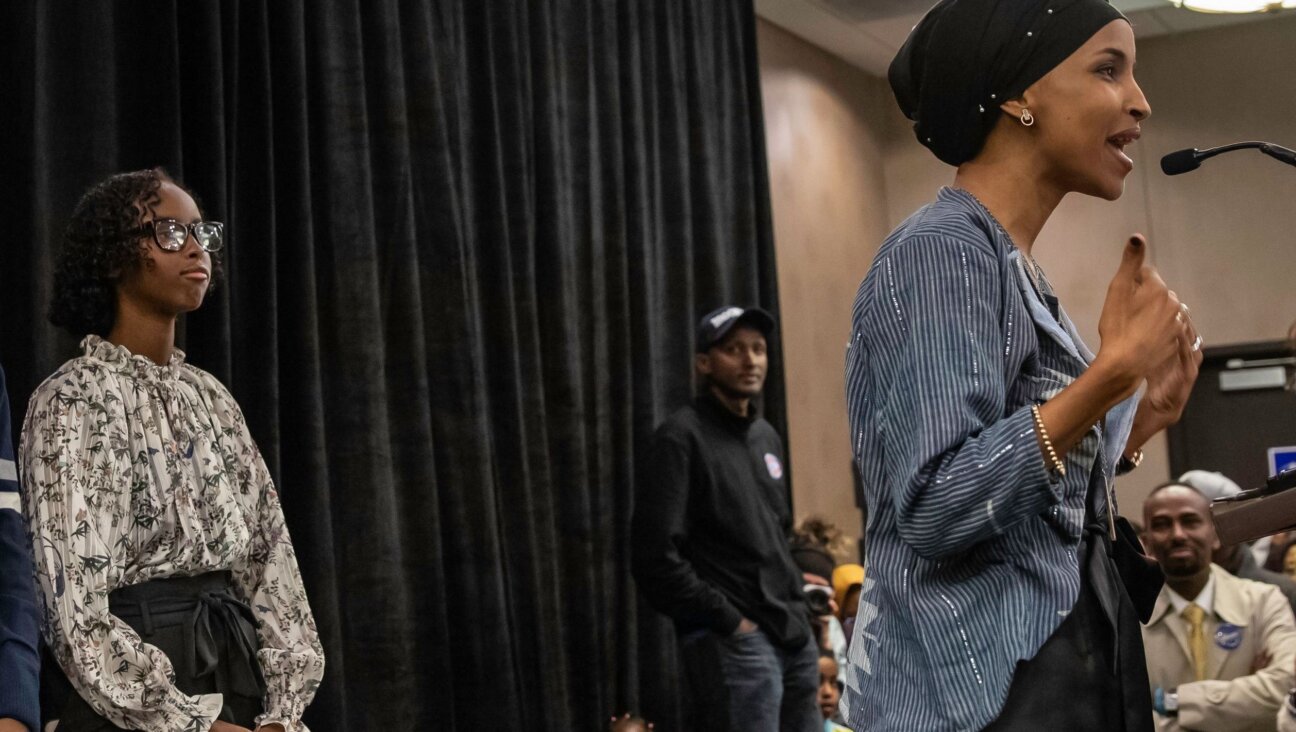

Image by itzik gottesman

Sanctuary in the Wilderness: A Critical Introduction to American Hebrew Poetry

By Alan Mintz

Stanford University Press, 544 pages, $65

Hebrew poet Gabriel Preil reads his work at YIVO in 1983. Image by itzik gottesman

The 19th-century German writer Heinrich Heine foresaw what would happen to his fellow Jews: “If Europe were to become a prison,” he mused, “America would still present a loophole of escape… Then may the Jews take their harps down from the willows and sit close by the Hudson to sing their sweet songs of praise and chant the lays of Zion.”

Well, they did come, and the retelling of their history, like a Hindu god, has taken many forms. Missing, however, has been a comprehensive discussion of the social history of American Jews’ “singing of sweet songs” — the literature in Hebrew, especially the poetic expression, of the American Jewish experience.

But wait! American Hebrew poetry? What’s that? Surprise is understandable, as the creation of a serious Hebrew poetry in the America of the first half of the 20th century is one of the best-kept secrets of American Jewish history. Why the poetry appeared is itself semi-mysterious; after all, most Jews who left Eastern Europe around the turn of the century did not go to the new Yishuv, the Jewish community in Palestine, but came to the United States. But among those who came to America were those who created the Tarbut Ivrit movement: The name means “Hebrew Culture,” but the movement was about much more. Ivrit was embedded in a person’s identity; Hebrew was “not only the dynamic force in Jewish life but the living tissue in daily life as well.”

The story of Hebrew in America and of American Hebrew literature (especially poetry) has been, for the most part, lost. The tale is now, at long last, deftly, winningly and compellingly spun by Alan Mintz in his watershed book, “Sanctuary in the Wilderness: A Critical Introduction to American Hebrew Poetry.”

“Sanctuary in the Wilderness” has two contexts. First, there is the Israeli context, primarily that of sh’lilat ha-golah — rejection of the Diaspora — the ideology that was regnant in the Yishuv, and was a basic Zionist assumption. The “American moment”? It simply did not exist; or if it did, it was retrograde. There was one center, and that was Palestine and later Israel.

Second, the American Jewish context, the context of pluralism, of urbanization, of American motifs: the romance of Native Americans, Manhattan’s Lower East Side, the lure of “California.” The story is that of the huge emigration from Russia from the 1880s to the 1920s, and an important part of that story is how ideologies and movements — absolutely central to the Eastern European Jewish persona — were lost, or became diluted, in America.

Mintz’s book is nothing less than a tour de force of literary and social history and literary criticism. Mintz, who is the author of a number of acclaimed works on Hebrew literature, including the masterful “Hurban: Responses to Catastrophe in Hebrew Literature,” weaves the Israeli and American contexts into a tapestry of portraits of 12 Hebrew poets who worked in the United States and who created an indigenous American Hebrew culture. Some of the poets — Hillel Bavli, Simon Halkin, Eisig Silberschlag, the great Gabriel Preil — are yet read, by some, years after their deaths. Others are forgotten, deserving of rescue, and Mintz reintroduces them to a new generation of American readers and historians.

As well as providing notes on the styles and significance of the writers, their biographies and their milieu, the literary selections in “Sanctuary in the Wilderness” serve as a chrestomathy of American Hebrew literature. Deftly curated and lovingly translated by Mintz, selections from the poetry are what make these chapters work. Preil (1911–1993), as bearer of the romantic Hebraism of his Lithuanian ancestors, expresses these connections when he compares himself with his grandfather, the rabbi of Kovno, who embodied the traits associated with Eastern European intellectual Orthodoxy. In “His and Mine,” Preil calls upon the reader to “See grandfather as a young man in his Lithuanian shtetl. / His habit was to rise early every morning / and after prayers he would write down his Torah insights / … See me as a young man on American soil / Not exactly an exceptional creature / who writes his poems in Hebrew. A man/who prays from silence…” Mintz chooses precisely the right poem to invoke “time, place, writing, and the routine of everyday morning” as points of comparison between the two complex lives — the poet and the rabbinic scholar.

Two essays introduce the book, in which Mintz sets a context for the “wilderness” and the “sanctuary” that was provided by America for the writers, and he explores how and why the “apotheosis of Hebrew” happened. The book closes with five essays — each of which alone would be worth the price of admission — that collectively address the question, “Would American Hebrew literature truly be American?” Mintz’s introductory chapters and the closing essays serve as effective “bookends” for the profiles of the 12 authors.

Mintz offers his book as an “academic study,” and it is indeed broad — polymathic, in fact — and deep. But don’t be gulled. Serious, yes, is “Sanctuary in the Wilderness,” but it is wonderfully accessible. Mintz is incapable of writing an uninteresting sentence; the book is a pleasure to read, and the reader will even learn something!

Having said this, Mintz does trip over a few linguistic paperclips. Abraham Zvi Halevi’s marvelous “Hadarim Meruhatim” (“Furnished Rooms”) invokes the fate of Zion in the use of the biblical question “Eicha?” translated by Mintz as simply “How?” But “Eicha?” resonant through thousands of years of Jewish tragedy, means much more: “How could this have possibly happened?” This nuance, crucial to the understanding of Halevi’s poem, is missing. “Khayat Bereshit” (also from Halevi) may mean “prehistoric creature”; more likely it is a borrowing from the Yiddish b’reyshis-dik, which, invoking the biblical narrative of creation, means “primeval” — which, in Halevi’s poem, is suggested by Brooklyn’s hulking Williamsburg Bridge at night. Again, a nuance in translation is missing.

The value of “Sanctuary in the Wilderness” is not that it is a watershed discussion of a literary arena that was forgotten, of writers that we simply did not know we had. Mintz is planting the flag firmly in the soil of American Hebrew poetry; his lucid discussions, however, are but the first step. “Sanctuary in the Wilderness” paves the way for a critical discussion, long overdue, of the poets represented in the volume, and of others in the American Hebrew oeuvre. The process of evaluation of the poets represented in the volume may now begin, and Mintz is the enabler of this process. Mintz’s claim is that our writers need to be refracted through the prism of American Jewish history; they are part of the American story. The American Jewish evaluation, therefore, will necessarily be different from the Israeli, which by virtue of its history and ideological traditions stands by a profoundly different set of evaluative criteria. Literary standards will count for less than national narratives.

Mintz’s peroration to the reader is nuanced, and appropriately so. He disagrees with the monomaniacal view of the American Hebraists that Hebrew is the measure of all things Jewish. (Mintz is spot-on in noting that this monomania was one factor that contributed to the eclipse of the Hebrew literary enterprise.) But Mintz does share the view of the Hebraists that Hebrew is the “deep structure of Jewish civilization, its DNA.” Whatever literary evaluation of American Hebrew poets may transpire, Mintz has revealed their link in this deep chain to our past, and thereby to our future.

Jerome Chanes is a contributing editor to the Forward. He writes about Jewish history, public affairs, and arts and letters.

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning journalism this Passover.

In this age of misinformation, our work is needed like never before. We report on the news that matters most to American Jews, driven by truth, not ideology.

At a time when newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall. That means for the first time in our 126-year history, Forward journalism is free to everyone, everywhere. With an ongoing war, rising antisemitism, and a flood of disinformation that may affect the upcoming election, we believe that free and open access to Jewish journalism is imperative.

Readers like you make it all possible. Right now, we’re in the middle of our Passover Pledge Drive and we still need 300 people to step up and make a gift to sustain our trustworthy, independent journalism.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Join our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Only 300 more gifts needed by April 30