Tangled Up in Jews

Image by Photo by Plouffe Studios

That Soggy Plain: Patrons try to stay dry on the Tanglewood lawn in 1955. Image by Photo by Plouffe Studios

It’s deeply ironic that Tanglewood, which is currently celebrating its 75th anniversary as the summer home of the Boston Symphony Orchestra and one of America’s largest music festivals — was essentially the creation of Jews in a place largely resentful of their presence.

During the 1930s in America, hostility to Jews was common, especially in rural areas, and the Berkshires were best known as a place of old-line Yankee farmers, famous American writers and high-society types. My uncle Zero, who broke into show business around the same time Tanglewood was founded, used to joke that back then, Jews didn’t go to the Berkshires — they went to the Catskills, which he called the “circumcised Berkshires.”

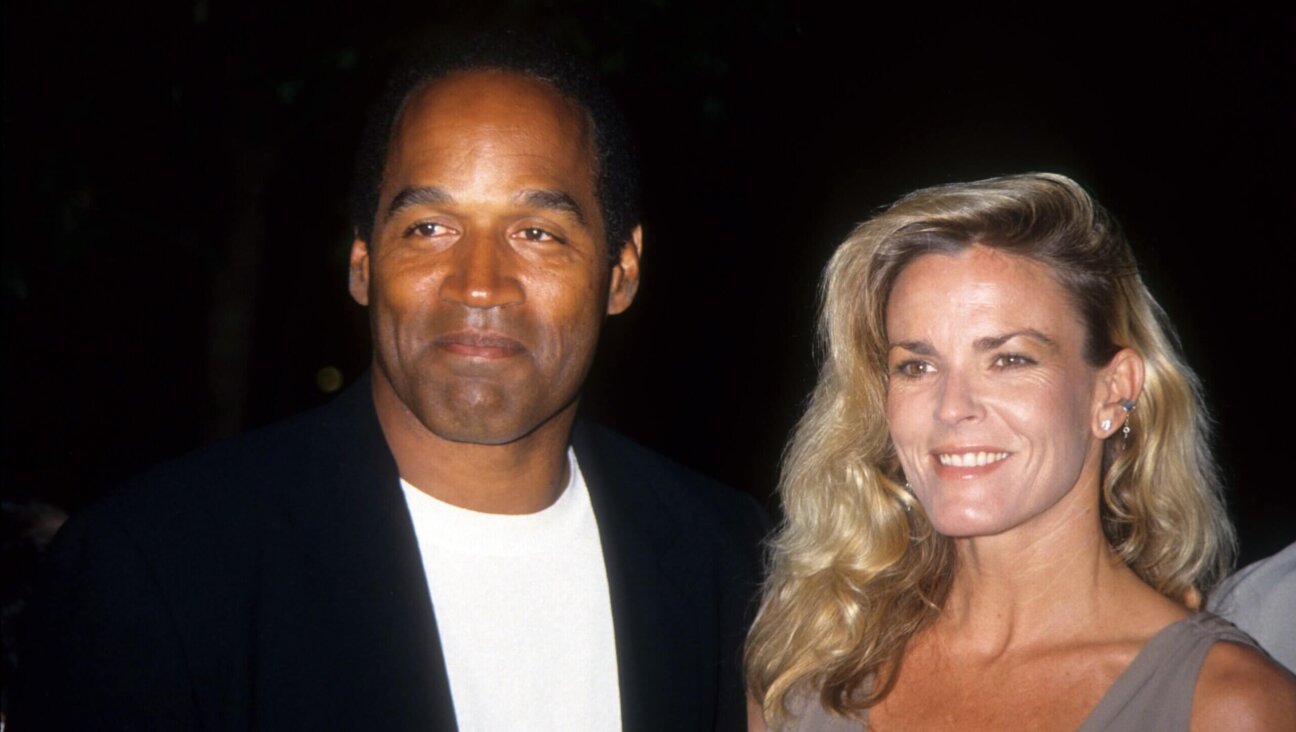

A Farewell To Lenny: Leonard Bernstein conducted his final concert at Tanglewood in 1990. Image by Photo By WAlter H. Scott

Read about The Jews of Tanglewood on our Arty Semite blog.

Nathaniel Hawthorne, who had rented a house in Lenox, Mass., in 1850 to write in seclusion — and wound up hating the place — coined the name Tanglewood. In Lenox, Hawthorne wrote “The House of the Seven Gables” as well as the lesser-known “Tanglewood Tales,” in which he retold Greek myths for children.

The Tanglewood festival itself began in the depths of the Great Depression. Gertrude Robinson Smith, the privileged daughter of a fabulously wealthy New York family who summered in the Berkshires, wanted to bring orchestral concerts to the country. Smith was an efficient sort. During World War I, she and her friend, writer Edith Wharton, organized medical supplies for France, even traveling to the country in a blacked-out ship and flying over the front lines. Smith was made a chevalier of the French Legion of Honor for her efforts. So, when she decided to start a music festival in 1934, she was up to the challenge. She introduced her festival in a cow pasture, under an August full moon, featuring musicians from the New York Philharmonic. Smith organized another festival the following year, but she wasn’t pleased with conductor Henry Hadley’s choice of repertoire: too light, not enough substance.

Check out Five Things You Never Knew About Tanglewood.

Enter Serge Koussevitzky, the “hot” new conductor of the BSO, who had been wowing audiences and critics not just with his conducting, but also with his “aristocratic, European” bearing that simply bowled over the Boston Brahmins — so much so that the BSO advertised itself as “the aristocrat of American orchestras.” Koussevitzky’s reputation, however, concealed his humble origins: He was actually the son of two Jewish klezmer musicians from a Russian shtetl. As a teenager he had been required to convert to the Russian Orthodox Church in order to be admitted to school in Moscow, and so to the Boston Brahmins he appeared to be merely an exotic Christian.

When Smith decided to engage the BSO to play in her cow field the next year, she met with “Koussy” — apparently, that’s what everyone called him — and shared her vision of creating “an American Salzburg Festival.” But he had an even larger vision: to create an educational institution within the festival to train future performers and promote the music of living composers. His initial concert included an arrangement of Bach by Arnold Schoenberg, who had arrived in America only recently, as a refugee from Hitler’s Europe.

After two more summers in the cow pasture (but in a tent), and one concert that was nearly drowned out by a thunderstorm, a hall was built, which became affectionately known as the “Shed.” Koussevitzky inaugurated the Shed with Bach’s chorale “Ein Feste Burg Ist Unser Gott”(“A Mighty Fortress Is Our God”) — an audience of 6,000 sang along — and with Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. He chose the Ninth because, he said, “it is the greatest work in musical literature… and because Tanglewood could, through Schiller’s ‘Ode to Joy,’ call all nations to brotherhood” — a sober thought, especially in 1938, the year of the Nazi Anschluss with Austria, occupation of Czechoslovakia, and Kristallnacht in Germany. The Berkshire Music Center, the educational facility now known as the Tanglewood Music Center, opened in 1940. By 1941, the campus added to the Shed the Theater-Concert Hall and Chamber Music Hall, and the festival was already attracting 100,000 visitors annually.

Koussy was passionate about developing a forward-looking culture of music, and also a specifically American symphonic culture. Pianist Oscar Levant once joked that Koussevitzky was “unparalleled in the performance of Russian music, whether it is by Mussorgsky, Rimsky-Korsakov, Strauss, Wagner or Aaron Copland.” Koussevitzky encouraged young composers and musicians many of whom happened to be Jewish. Even though merciless about Koussevitzky’s personal and professional shortcomings, critic Norman Lebrecht wrote, “No one gave more support to composers exiled by Nazis.” Even Stravinsky, who called him a hypocrite, a megalomaniac and worse epithets, remembered with reverence “those things Serge Koussevitzky did for others without telling anyone.”

Aaron Copland, who perhaps more than any other composer created the “sound” that Americans associate with the concept of “America,” was one of the greatest beneficiaries of Koussevitzky’s efforts. The BSO premiered many of his compositions. Copland became Koussevitzky’s assistant director at the center, whose faculty included numerous other Jewish musicians, notably cellist Gregor Piatigorsky. Among the first students to benefit from Koussevitzky’s interest was Leonard Bernstein, who became almost synonymous with Tanglewood; he performed and taught there, and in 1990 he conducted his last concert at Tanglewood.

Inspired by Koussevitzky’s example, Paul Fromm, a Jewish refugee from Hitler’s Germany who had made a fortune in the wine business, sponsored a series of contemporary music concerts within the Tanglewood festival in 1956, and continued to do so for almost 30 years. Fromm eventually ended his sponsorship in 1984 to protest Gunther Schuller’s refusal to program music of such new composers as John Cage and Steve Reich. But Fromm’s idea of a contemporary music festival-within-a-festival remained and still endures, as does his foundation to commission new scores.

Although Koussevitzky himself is buried in a Christian cemetery in Lenox, in his last concerts he conducted the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, and after a highly emotional concert in Tel Aviv, he decided to donate his entire music library to the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, stipulating that any Israeli ensemble could use the materials. His widow, Olga Koussevitzky (niece of his second wife Natalie), together with Bernstein formed the Music for Israel Committee. Seranak — his Lenox estate, named by combining the names Ser(ge) a(nd) Na(talie) K(oussevitzky) — has become a shrine to his memory. The estate now serves as housing for many of the festival’s visiting artists. Koussevitzky’s clothes and shoes are still kept in his room there, as if he’d only gone on a trip.

If Koussevitzky returned, he might be surprised at the size of the Tanglewood Festival, but he certainly would recognize it, as he established the blueprint for everything it has become. It has doubled in size, acquired a new concert hall and enjoys at least 350,000 visitors annually, but it is all still the realization of the original, far-reaching vision of this son of two shtetl musicians who, as critic Lebrecht put it, “gave America a thriving heartland of music creativity.”

From now until September 2, Tanglewood offers free Web streaming of historic Tanglewood performances — 75 in all.

Raphael Mostel is a composer based in New York City (www.mostel.com).

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning journalism this Passover.

In this age of misinformation, our work is needed like never before. We report on the news that matters most to American Jews, driven by truth, not ideology.

At a time when newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall. That means for the first time in our 126-year history, Forward journalism is free to everyone, everywhere. With an ongoing war, rising antisemitism, and a flood of disinformation that may affect the upcoming election, we believe that free and open access to Jewish journalism is imperative.

Readers like you make it all possible. Right now, we’re in the middle of our Passover Pledge Drive and we need 500 people to step up and make a gift to sustain our trustworthy, independent journalism.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Join our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Our Goal: 500 gifts during our Passover Pledge Drive!