A Second Chance at a Yiddish Poem

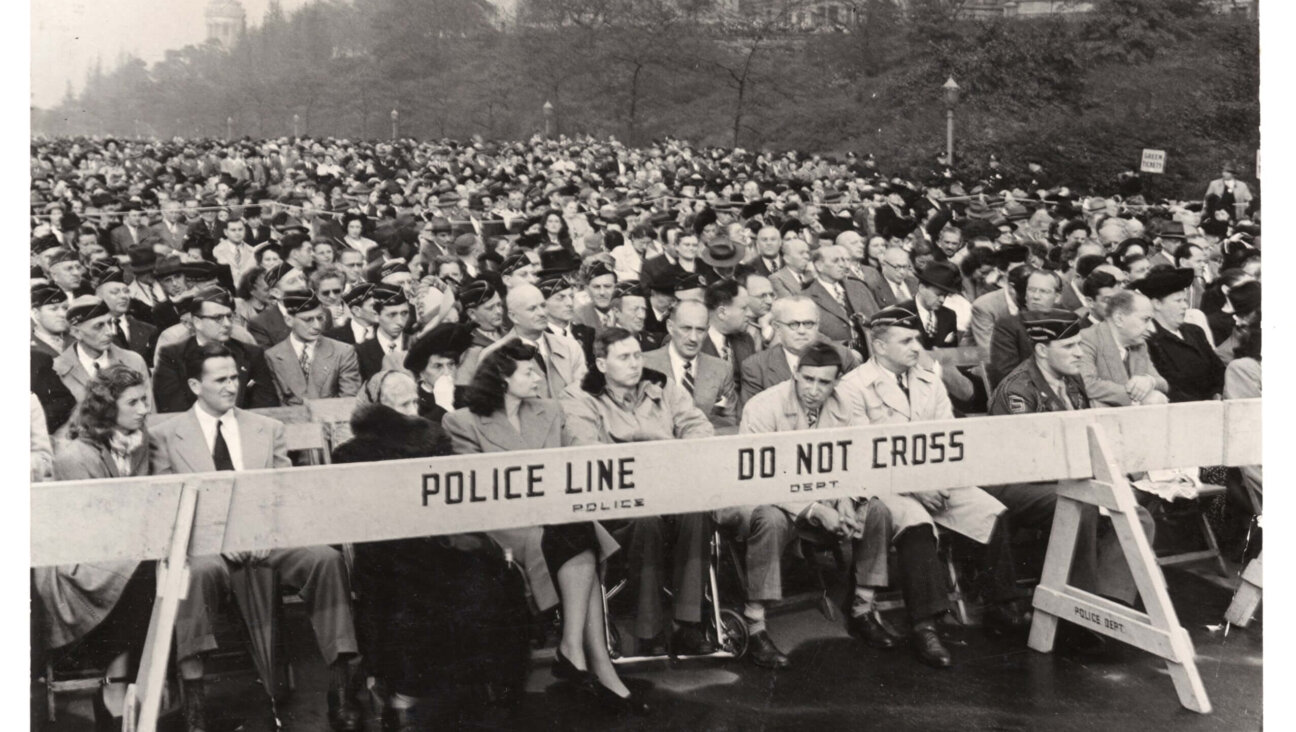

Totalitarianally Committed: The subject of Abraham Liessin?s poem turns out to be a faithful Stalinist. Image by Getty Images

Three readers — Daniel Soyer, Hirshl Hartman and Ben Ross — have written to correct a mistake I made in my June 7 column, “Whose Broad Noodles and Bright Farfel.”(The titles of my columns, by the way, are chosen by the Forward, not by me.) This occurred in my translation of Abraham Liessin’s 1938 Yiddish poem “Sereh: The Banquet,” in which I rendered the term biznes-agent as “businessman-gent.” Not that any of the three thought I was confusing agents with gents; they all understood that this was done for the sake of rhyming metrically with the phrase in the next line, “es klept zikh bay im tsu di hent.” But as Mr. Soyer points out:

“A biznes-agent is a ‘business agent,’ the union official charged with enforcing the contract in the shops, and ‘es klept zikh bay di hent’ [literally, “It sticks to his hands”], means that he has ‘sticky fingers’ — that is, the business agent takes bribes from the bosses to look the other way when it comes to labor violations. In the old days, the Communist Party [which Liessin satirizes in his poem] would have raised a stink [about the presence of a business agent at a left-wing banquet], but now that, in Liessin’s words, the Party has become statetshne — polite or well mannered — it keeps quiet about it.”

Mr. Hartman concurs:

“Your ‘businessman-gent’ was in fact the functionary in the ILGWU [International Ladies Garment Workers Union] and other unions who oversaw employers’ adherence to contract rules, especially payment of checked-off union dues and contributions to health and retirement funds. The business agent, therefore, was considered by radicals a tool in the slimy hands of the union bosses.”

And Mr. Ross adds:

“Once the Communists were defeated in the ILGWU in the late 1920s, the business agents tended to be the right wing of the union, more interested in day-to-day management of the workplace than in social reform.”

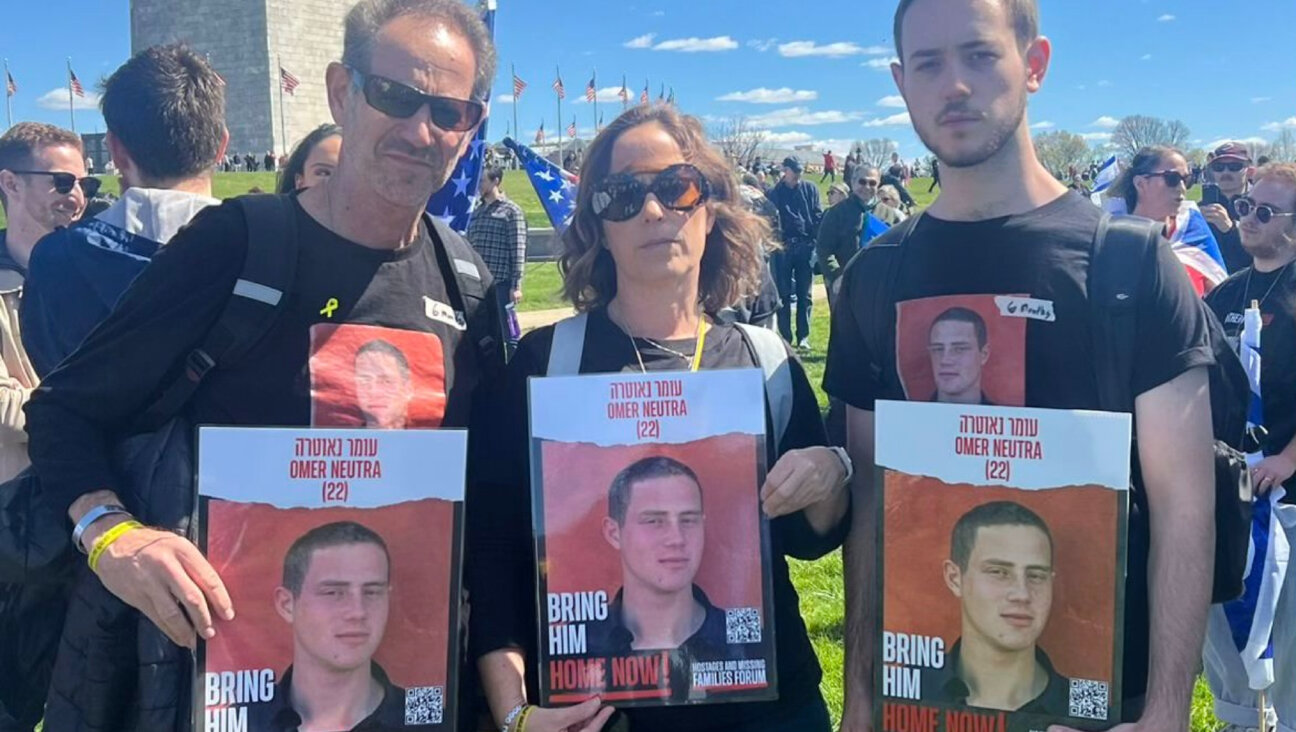

It gets more embarrassing than that. Mr. Soyer (with great tact, I must say) then goes on to observe that I misunderstood not only the term biznes-agent, but also Liessin’s entire poem. Its character of Sereh or Sarah, he writes, is not, as I thought, that of a veteran anti-Communist socialist who is the guest of honor at a Communist Party-sponsored banquet because the party line has switched to the “Popular Front,” a broad left-wing coalition including social-democratic forces. On the contrary, she is a militant Communist who is mortified by the new line and sits through the dinner in her honor — at which the Stars and Stripes fly high and there are union business agents among the guests — gritting her teeth.

Mr. Soyer is undoubtedly right, and I can only say that, in my defense, I had but a small part of Liessin’s 10-page poem in front of me when I wrote the column.

It’s a more subtle and moving poem than I described it as being, because Liessin’s Sereh, though teased by the poet for her ideological bellicosity, is also sympathized with as a woman who has given her life to a cause whose leaders, followed by her blindly, have suddenly changed their tune. As she sits listening to the banquet’s speakers and their new tone of moderation, she thinks of how, not long ago, she was leading a march through the streets of Manhattan:

Ot yogt zi af fertsnter gas un zi shalt,

Ir gvardye ir kemfnde yogt mit ir mit;

Es klapt zikh di tufles op on asphalt

Azh ‘skayskryepers’ tsitern unter di trit.

O soshl-fashist! O, rukt zikh avek!

Tsi zet ir nit den vi di mas-akstye geyt…?

Freely translated:

Down 14th Street she storms with a whoop and a shout,

And her fellow fighters stride in her wake;

Their shoes pound the pavement until it’s worn out,

And even the skyscrapers tremble and quake.

O social-fascists! Out of our way!

Can’t you see that the masses are marching today?

“Social-fascist,” like “business-agent,” was a new term for me. It dates to the sixth congress of the Comintern, the Communist International, in Moscow in 1928. There, Stalin declared that there was no difference between the fascist and social-democratic parties of Europe, which were “twin brothers” in opposing the spread of Bolshevism. The Communist refusal to collaborate with the Social Democratic Party of Germany in the fight against Hitler was partially responsible for the latter’s rise to power in 1933, and subsequently, Stalin did a turnabout and announced, in 1934, the Popular Front policy.

Liessin’s Sereh is a faithful Stalinist, but it’s nevertheless difficult for her to accept the “social-fascists” of yesterday having become her comrades of today. The poem ends with her back in her apartment, staring at the bouquet of flowers she has been given and bewilderedly mourning the years she devoted to fighting an enemy with whom she now has to share a banquet table.

Questions for Philologos can be sent to [email protected]

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning journalism this Passover.

In this age of misinformation, our work is needed like never before. We report on the news that matters most to American Jews, driven by truth, not ideology.

At a time when newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall. That means for the first time in our 126-year history, Forward journalism is free to everyone, everywhere. With an ongoing war, rising antisemitism, and a flood of disinformation that may affect the upcoming election, we believe that free and open access to Jewish journalism is imperative.

Readers like you make it all possible. Right now, we’re in the middle of our Passover Pledge Drive and we need 500 people to step up and make a gift to sustain our trustworthy, independent journalism.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Join our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Our Goal: 500 gifts during our Passover Pledge Drive!