The Bottom Line

First published in Makor Rishon, October 2008

“So how do you get on with other cartoonists? I mean, isn’t it rare for an Israeli cartoonist to be a right-wing religious settler?”

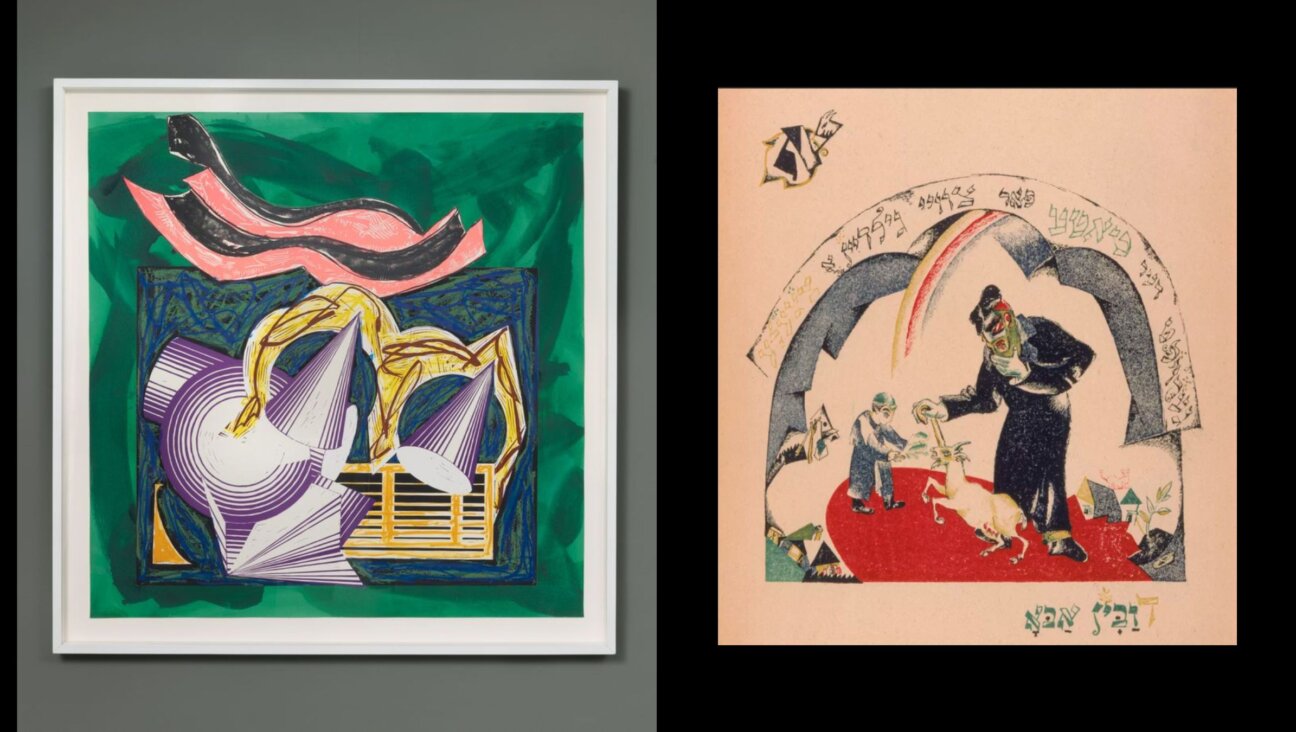

Fink and Charka put each other to the pencil. Image by Courtesy of Shay Charka

It was a fair question. More than 80 educators from San Francisco had been listening to and looking at the work of Shay Charka and were both impressed and disturbed. Charka’s work was original, charming and sharp. But its sentiments were very much out of line with the assumptions of normal self-respecting liberals to whom they were accustomed.

First of all, it was clear that Charka wasn’t impressed with their president. They had winced when they saw the cartoon he had published the day after Obama’s election, with the president floating on a hot air balloon of his own making.

Nor were they particularly impressed with Charka’s attitude toward the wrangling over building in the territories. Here again, just like with the Obama cartoon, his approach was deliberately de-mystifying, humanizing and decidedly not politically correct. The absurdity of political obfuscation is gently brought to earth, as a religious child innocently asks his pregnant mother if his tree house might be classed as an illegal outpost according to international standards.

So how did Charka get on with the left-leaning world of Israeli cartoons?

Charka jumped off his chair, grabbed a marker pen and moved over to the flip chart. While sketching out the deliberate lines of his drawing, he explained that he was a good friend of Uri Fink, a Tel Aviv-based cartoonist. Recently they had each produced a book and had chosen to throw a joint launch party. For the event publicity, they had drawn a joint cartoon, Charka explained as he sketched out a replica. On the left (of course) the left-winger, Fink, is trying to “redraw” Charka (on the right) into a lefty, and Charka’s character is trying to “redraw” Fink into a settler — complete with Uzi machine gun.

Charka explained that in the early drafts, he, Charka, had drawn land under both their feet. But the final draft ended up with no lines under the feet of Fink, leaving Charka the only one standing on land.

Charka went on to explain that for him, this is the key difference between left and right in Israel. He can no more delete the lines indicating the land on which he stands than he can delete the lines of his nose. Land is part of his identity. It is part of who he is. The left-wing Israeli has no such attachment.

As the facilitator of this session, I asked him the follow-up question that was in the air:

“If you are on the land, and the left-wing Israeli is in the air, how would you draw a Diaspora Jew who doesn’t even live in the Holy Land?”

Before he could begin to reply in words, I thrust the marker pen back into his hand.

His immediate response? He got up and drew Art Spiegelman’s Maus.

“A mouse? The Diaspora Jew is a mouse?” I said, breaking the shocked silence.

“Yes,” Charka replied comfortably, “a mouse lives in a hole. It may be a very nice hole with very pretty things inside. But in the end, it is still a temporary dwelling from which he will flee when the cat comes calling.”

The silence reverberated threefold. First, no one could quite believe that Charka had not politely backed down. Second, the image he had drawn, and his innocent attitude toward it, was so unintentionally challenging that the chasm of understanding between Charka and the audience was dizzying. Third, the confidence with which he had described what he saw as the fatal illusion of a Diaspora lifestyle was terrifyingly, though temporarily, convincing. For a second, one could feel everyone imagining the cat outside the door — before shaking off the image with an impatient shudder.

Charka was not deliberately trying to be provocative. That’s not his style. In general, his work calls for moderation and for awareness of complexities. One of his famous critiques of his own settler movement is a wordless portrayal of the futility of violent behavior that the Peace Now camp condemns but exploits. At the same time, the settler-dragged tractor carrying the left-winger, feet up on the driver’s seat, hints at the inherent laziness of the left.

When Charka sketched out the way he saw the Diaspora, he was just being honest. While Israeli educators know by now that such a “negation of the Diaspora” is ineffective, this does not mean that many Israelis do not nevertheless subscribe to its basic classic-Zionist thesis.

Charka was very much aware that he’d upset people, and that troubled him. He couldn’t quite figure out what he’d done wrong. Perhaps, he wondered out loud, I meant only European Jewry and not American Jewry?

A few weeks later, I met him with a different group and asked him the same question about the Diaspora Jew. This time he was ready. He said it had been unfair of him to mix metaphors. The two Israelis he’d portrayed were human, yet he’d drawn the Diaspora Jew as an animal. This offended his cartoonist’s sense of aesthetics. If he were to draw the Diaspora Jew’s relationship to land using a human metaphor, he would refer to Sholom Aleichem, not to Spiegelman, and draw him as a fiddler on the roof.

This time the Jew in the Diaspora is nowhere near the ground, nowhere near the Holy Land. We have left the world of the Holocaust and reached back toward the days of pogroms instead.

It is a more respectful image than the rodent, but it’s still an image of a world gone by, one that this influential Israeli cartoonist sees as current. It would seem that according to Charka’s perspective, which he no doubt shares with many other Israelis, the Diaspora is the land of graves, or of soon-to-be graves. As both his explanation of the mouse, and the loving reference to Sholem Aleichem attest, this vision of Diaspora evinces much love for the Diaspora culture. The fiddler on the roof makes wonderful music, after all. But at the same time the images display a strong conviction that in the long run, he is doomed.

While we may bemoan the way in which Diaspora Jews view Israel only through the lens of war, through issues of life and death, it would seem that a certain proportion of Israeli Jews see the Diaspora through the same lens of survival-odds.

When using words rather than images, Charka himself places more emphasis on the way that both the mouse and the fiddler are disconnected from land, unaffected by place: “So long as someone is not attached to a place, they will never fight for it.”

Whether we are mice or fiddlers, as the struggle over settlements intensifies we will see many more people willing to fight for the land they live on. Before sighing in exasperation, we might do well to look below our own feet, and look out for the lines of earth extending from them. How easily might we choose to delete those lines?

Robbie Gringras is a writer, performer and educator working as artist-in-residence for Makom.

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning journalism this Passover.

In this age of misinformation, our work is needed like never before. We report on the news that matters most to American Jews, driven by truth, not ideology.

At a time when newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall. That means for the first time in our 126-year history, Forward journalism is free to everyone, everywhere. With an ongoing war, rising antisemitism, and a flood of disinformation that may affect the upcoming election, we believe that free and open access to Jewish journalism is imperative.

Readers like you make it all possible. Right now, we’re in the middle of our Passover Pledge Drive and we still need 300 people to step up and make a gift to sustain our trustworthy, independent journalism.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Join our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Only 300 more gifts needed by April 30