Middle East Politics Beyond Cohen’s Grasp

Beyond America’s Grasp: A Century of Failed Diplomacy in the Middle East

By Stephen P. Cohen

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 304 pages, $27

The only thing arguably more horrible than events in the Middle East is how large elements of Western academia, and sometimes the media, present the region. The other day, I remarked to a Syrian dissident in a position to know both sides very well that a lot of the writing and teaching on the region in the United States was very close to how it is presented at the University of Damascus. He concurred.

Thus, if people in the West wonder why they don’t understand the area and why their predictions go so wrong, the answers are easily found. A lot of this reality is hidden by debates over “pro-Israel” or “pro-Arab,” and over the political “left” versus the “right.” The key issue isn’t partisanship — though that can be the source of the problem — but rather ignorance, lack of logic, conclusions predetermined by ideology and simple sloppiness.

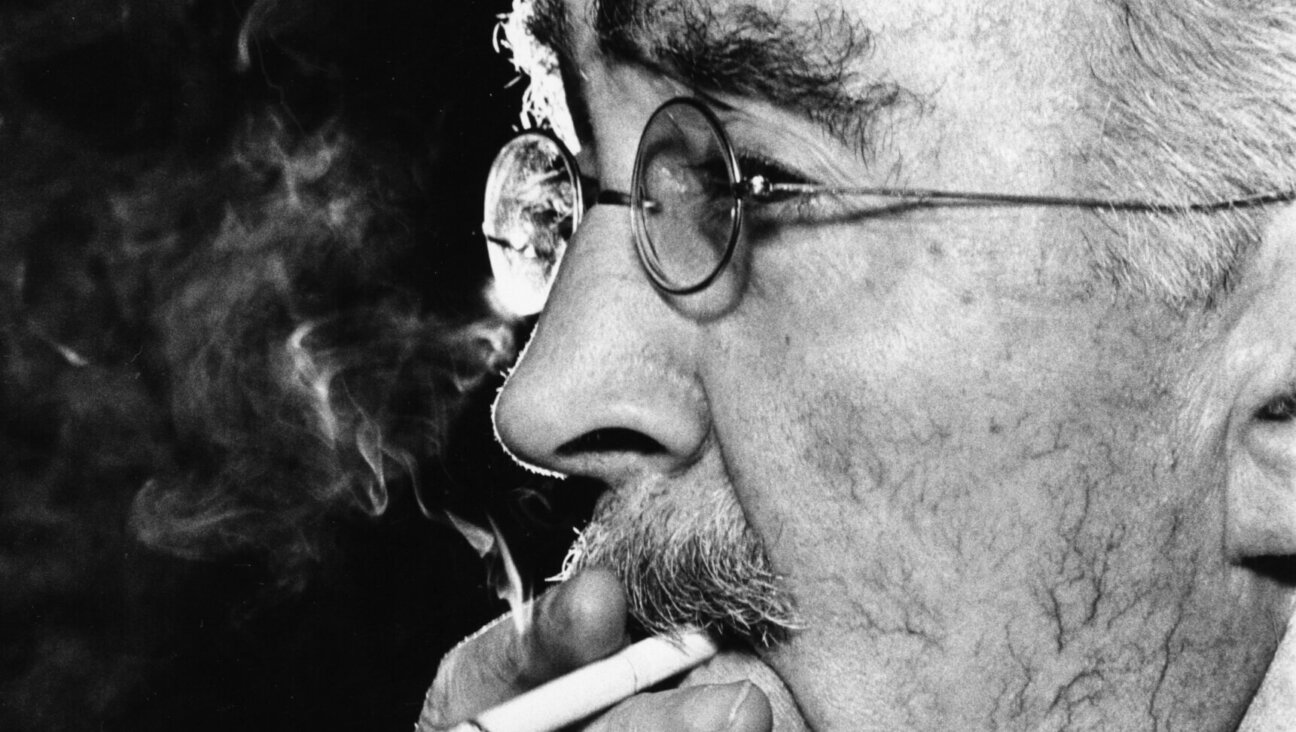

Players: Gamal Abdel Nasser with Nikita Khrushchev. Image by WIKI COMMONS

All of which brings us to Stephen P. Cohen’s “Beyond America’s Grasp: A Century of Failed Diplomacy in the Middle East.” This is simply one more of innumerable histories of America’s Middle East policy, a topic that has been covered by scores of books already, most of them far better than this one. Indeed, this book does not bring a single new fact to light, which is not surprising, since it does not consult a single archival document despite the massive amounts of material available in the National Archives, U.S. State Department publications and presidential libraries.

So what’s the point of publishing a superficial book that repeats what’s been gone over hundreds of times, adds nothing, has an analysis that is ludicrously simplistic and is full of inaccuracies? I can’t imagine.

For many years, and especially in the aftermath of 9/11, the Middle East has been a playground for those whose hypothesis is unmatched by knowledge. Running around the world and chatting with people is no substitute for a deep understanding of the context and the players. In this case, no matter where one looks in this book, the contents are just inaccurate — and they seek generally to make the United States look silly. Cohen’s analysis is based mostly on stereotypes at worst and on repetitions of what has been written better elsewhere at best.

For example, in a brief evaluation of the history of the conflict, we read:

In the Suez period, the United States tended to view all events through the lens of cold war competition and confrontation and could not measure Arab nationalism and inter-Arab rivalry on its own terms. It could never seem to grasp that this was not the lens through which the Arabs saw the world. The Arabs were seen by America as too fractious and simply would not be made to fit on the Procrustean bed of American cold war foreign policy.

This is what one would expect in a term paper from an undergraduate who didn’t know much except for some clichés about American policy in the 1950s. In fact, policymakers in the United States were very much aware of these factors and did not see the region in starkly Cold War terms. After all, in the Suez Crisis, the United States essentially backed Egypt against its own British and French allies despite that country having being a Soviet ally, which shows that American policy was the precise opposite of what the author claims — precisely because it was so aware and concerned about Arab nationalism.

Moreover, in the days leading up to Egypt’s 1952 coup, America’s government had opened lines with the Arab nationalist plotters because they viewed Arab nationalism as an important force in its own right and were ready to make considerable concessions to it. The author seems unfamiliar with the extremely important April 1, 1956, State Department memorandum in which inter-Arab rivalry was analyzed. The conclusion was that Egyptian dictator Gamal Abdel Nasser was seeking to overthrow countries friendly to the United States in the region — Jordan, Saudi Arabia and Iraq among them — for his own reasons, though he was also allied with Moscow. The State Department read the situation quite correctly.

A similar response could be given to most of the rest of this mediocre book. When it comes to advice or current issues, the author seems remarkably detached from reality:

The American university system and the educational systems in general, must be encouraged to educate for tolerance and beyond tolerance, respect for Islam as a fierce advocate of monotheism and a strong advocate, in its sacred texts, of social justice.”

Outside of those hiding in caves on the Afghanistan-Pakistan border, it is hard to imagine anyone unaware — whether one approves or disapproves — that American schools approach Islam with a respect unequalled for any other topic. Not only is criticism of Islam as one of a number of historical religions severely curtailed, but even the usual scholarly methods are close

to being banned, as well. The problem is that this paralysis prevents an understanding of any relationship whatsoever between Islamic doctrine and dictatorship, or between the former and political Islam, terrorism, the treatment of women and other issues.

That one could go on and on and write a response triple the length of this volume is testament to the number of poorly or wrongly substantiated and analyzed assertions this book makes. Suffice it to say that this is the worst book I have read on America’s Middle East policy in many years, and that’s saying quite a lot.

Barry Rubin is the director of the Global Research in International Affairs (GLORIA) Center and the editor of the Middle East Review of International Affairs journal. His latest book is the seventh edition of “The Israel-Arab Reader” (Penguin Putman, 2008).

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning journalism this Passover.

In this age of misinformation, our work is needed like never before. We report on the news that matters most to American Jews, driven by truth, not ideology.

At a time when newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall. That means for the first time in our 126-year history, Forward journalism is free to everyone, everywhere. With an ongoing war, rising antisemitism, and a flood of disinformation that may affect the upcoming election, we believe that free and open access to Jewish journalism is imperative.

Readers like you make it all possible. Right now, we’re in the middle of our Passover Pledge Drive and we need 500 people to step up and make a gift to sustain our trustworthy, independent journalism.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Join our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Our Goal: 500 gifts during our Passover Pledge Drive!