Vienna’s Most Jewish Street

Home Sweet Home: A doll’s room owned by the Przibam family. Image by Peter Kainz/MAK

Growing up in Vienna means that your primary school education included memorizing the first stanza of the Blue Danube Waltz (“Die Donau so blau, so blau, so blau…”), knowing when the Ottomans unsuccessfully laid siege to Vienna (1529 and 1683), and learning about the city’s best-known boulevard, the Ringstrasse. While I might not recall all the details we were taught about the latter (why did the architect of the opera house commit suicide again?), the broad story has stuck in my head: In the mid-19th century, the city was growing, and young emperor Franz Joseph decided to dismantle the walls that still surrounded the city center and replace them with a stately boulevard.

Well done, FJ, the 8-year-old me thought as I sat in the tram that used to circle the Ring, as the Viennese call it, and looked at the impressive buildings that we zipped past, such as the university, the city hall, parliament, the Burgtheater and the opera. Good old Franz Joseph knew a thing or two about effective photo backdrops.

This year, the Ringstrasse is celebrating its 150th anniversary, and with all the political and historical events to commemorate the year (such as the Vienna Congress of 1915, the end of World War II in 1945 and Austria’s treaty of independence in 1955), I expected this to be a straightforward, joyful occasion. What’s not to feel proud about, especially after the part of the Ringstrasse named after the anti-Semitic Vienna mayor Karl Lueger was finally renamed Universitätsring? (It was in 2012, but, hey, better late than never.)

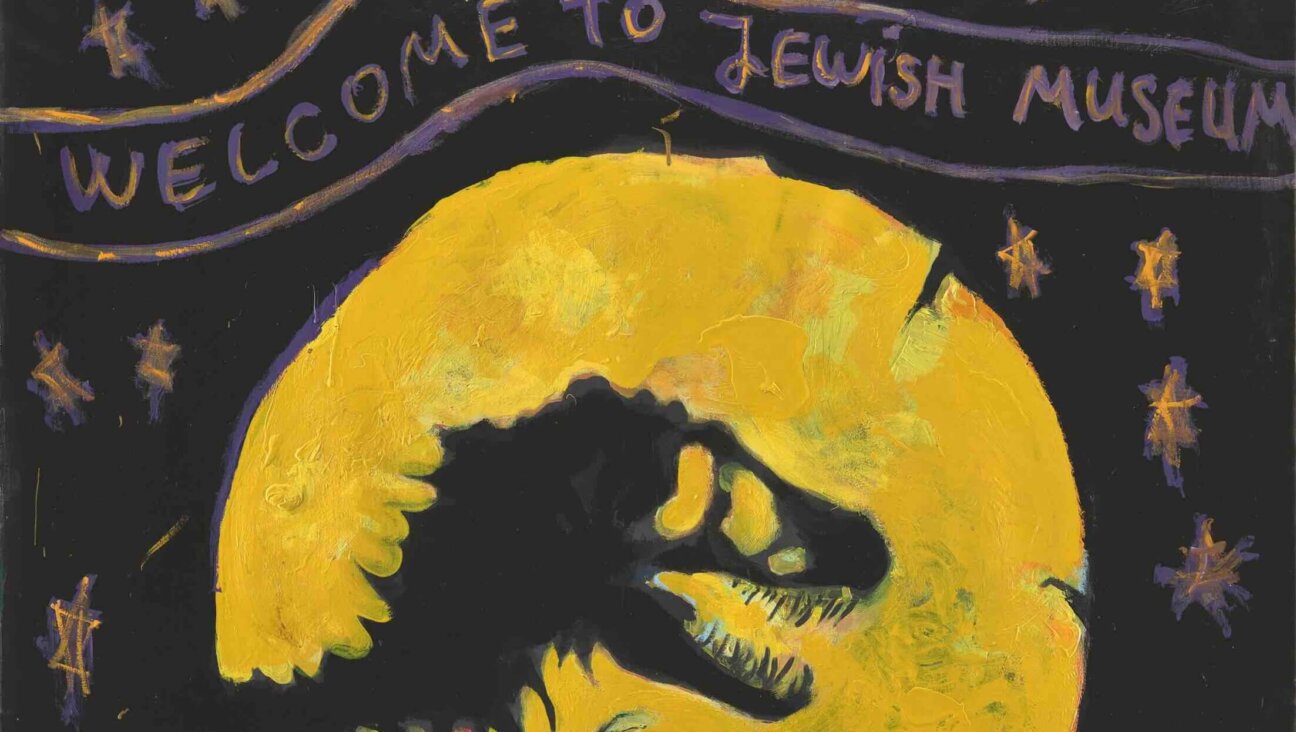

Enter the Jewish Museum Vienna, which uses its new exhibit to remind us that the Ringstrasse boasts a Jewish history that isn’t yet well known. With almost half of the privately held lots owned by Jews, the boulevard was a symbol of Jewish economic success, patronage — and assimilation. Along with much of the bustling, Austrian Jewish life, it ended abruptly in 1938. Aptly titled “Ringstrasse. A Jewish Boulevard,” the exhibit, which runs until October 4, does a great job of showing the basics of the story.

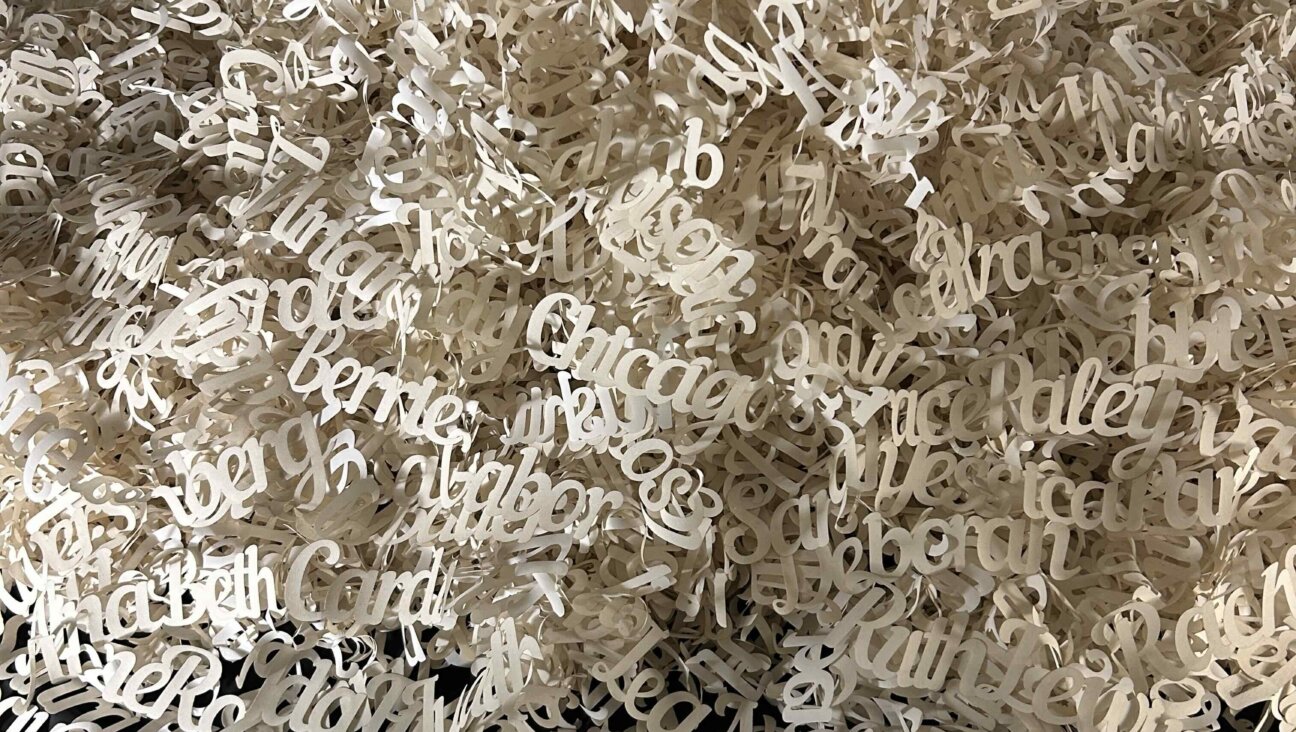

In December 1857, Franz Joseph gave the orders to dismantle the city walls. About two years later, in early 1860, when the lots on the new boulevard were ready to be sold, he issued a new law that allowed Jews to own land (a first in the Habsburg Empire). That worked out in his favor, since the Jewish bourgeoisie was eager to establish itself — both geographically and socially — in the center of the Habsburg Empire. Of the privately held lots on the Ring, Jews soon owned 44%. A map in the museum shows around 20 Jewish palais, or mansions, at or near the Ringstrasse; they were named after the families — such as Todesco, Ephrussi, Lieben and Auspitz — that lived there.

Proud and Viennese: A photograph of the Lieben family around 1870. They lived on Universitätsring 4, across the street from the city hall. Image by Victor Angerer

Oh, and how those families lived! We get to see photos and sketches of the interiors, as well as a doll’s room that was owned by the Przibam family, who lived in two stately homes on the Ringstrasse. One can assume that the room was modeled after the Przibam cribs, complete with miniature-sized family photographs. We also learn that the architects (among whom were a handful of Jews as well) conceived the interior as a coherent work of art, meaning that the families lived in (not-so-) mini-museums.

Next we learned some fun facts about the families that inhabited these palaces. Perhaps unsurprisingly, they considered themselves assimilated — some were even baptized — and favored political liberalism. Many families were related to each other. Some fostered a vivid salon culture with performances, readings and get-togethers; others were patrons of the arts, and some gave generously to charity.

While wandering through the rooms of the exhibit, I found myself wishing I could get to know one or two families a bit better. I saw their letters, furniture and photographs, but all I was introduced to were some basic biographical facts of the tenants. Then I remembered that I could just go home and reread Edmund de Waal’s “The Hare With Amber Eyes.” It tells with colorful detail the story of the Ephrussi family, who lived on what’s now Universitätsring until 1938.

The exhibit dutifully mentions that, even though Jews invested in Vienna’s stately boulevard, that didn’t make anti-Semitism go away, and it shows some horrific caricatures to illustrate it. Significantly more space and effort are dedicated to the events following the Anschluss in 1938. No surprises here, either. Even though most of the Jewish Ringstrassen families were able to escape persecution, they had to leave most of their belongings behind. Many of those weren’t returned to the rightful owners until more than 70 years later.

Behind the Curtains: The exhibit runs until October 2015 at the Jewish Museum Vienna. Image by Eva Kelety

One detail that was new to me concerned the former Hotel Metropol, which was owned by the Jewish Klein family and was turned into the Gestapo headquarters after it was Aryanized: I had no idea that the inventory of the hotel was used to furbish the Lebensborn homes, where “racially pure” children of German women and of SS and Wehrmacht officers were raised.

The ambitious exhibit tries to cover a lot of different topics. Perhaps learning a lesson from , the curators have kept explanatory texts to a minimum, but I could have done with some more details and historical background.

Leaving the museum, I walked through the inner city, past the former Ephrussi mansion (which has a Starbucks, a book store and a butcher shop/bakery on the street level) and turned onto the Ringstrasse. I looked down the busy boulevard and found it impossible to imagine Vienna without it.

Anna Goldenberg is the Forward’s culture fellow.

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning journalism this Passover.

In this age of misinformation, our work is needed like never before. We report on the news that matters most to American Jews, driven by truth, not ideology.

At a time when newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall. That means for the first time in our 126-year history, Forward journalism is free to everyone, everywhere. With an ongoing war, rising antisemitism, and a flood of disinformation that may affect the upcoming election, we believe that free and open access to Jewish journalism is imperative.

Readers like you make it all possible. Right now, we’re in the middle of our Passover Pledge Drive and we still need 300 people to step up and make a gift to sustain our trustworthy, independent journalism.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Join our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Only 300 more gifts needed by April 30