Miriam Schapiro Married Judaism and Feminism in Her Art

Toronto-born Miriam Schapiro, who died on Saturday, June 20, at the age of 91, proved that an ardent feminist can also be a joyous artist. Born in 1923 to Russian Jewish parents, Fannie Cohen and Theodore Schapiro, she had a rich and varied imagination, as described in Thalia Gouma-Peterson’s “Miriam Schapiro” from Harry N. Abrams Publishers (1999). Her father, an industrial designer, studied at the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design, then a leading Manhattan vocational school, while her mother, a staunch Zionist, encouraged young Miriam, who had begun drawing at age six, to become a professional artist.

A graduate of Brooklyn’s Erasmus Hall High School, Schapiro, who called herself a “cultural Jew,” would marry the American Jewish abstract painter Paul Brach (1924-2007), who developed her interest in Yiddishkeit and modern Jewish history. While serving in the armed forces during the Second World War, Brach saw Theresienstadt concentration camp soon after it was liberated by Soviet troops in 1945.

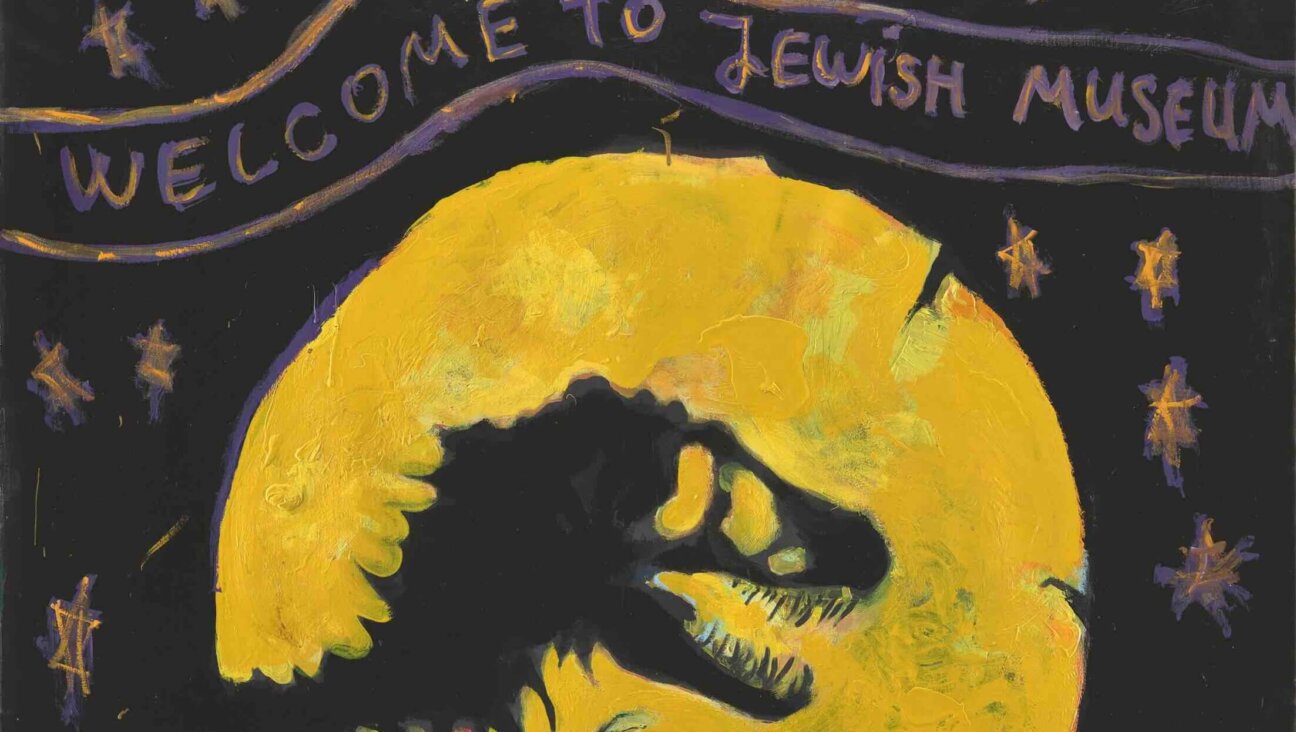

Schapiro especially explored her Jewish identity during the 1980s: a series of images of monumental Golems was followed by numerous works in tribute to the leftist Mexican painter Frida Kahlo, who claimed Jewish ancestry. Schapiro’s clear identification with Kahlo as a female artist was accompanied by a further series of paintings in homage to the French Jewish artist Sonia Delauney (1885–1979), a co-founder of the Orphism movement, known for powerful colors and geometric shapes. Like Schapiro, Sonia Delauney was married to a painter, Robert Delaunay, although Schapiro and Brach worked more independently.

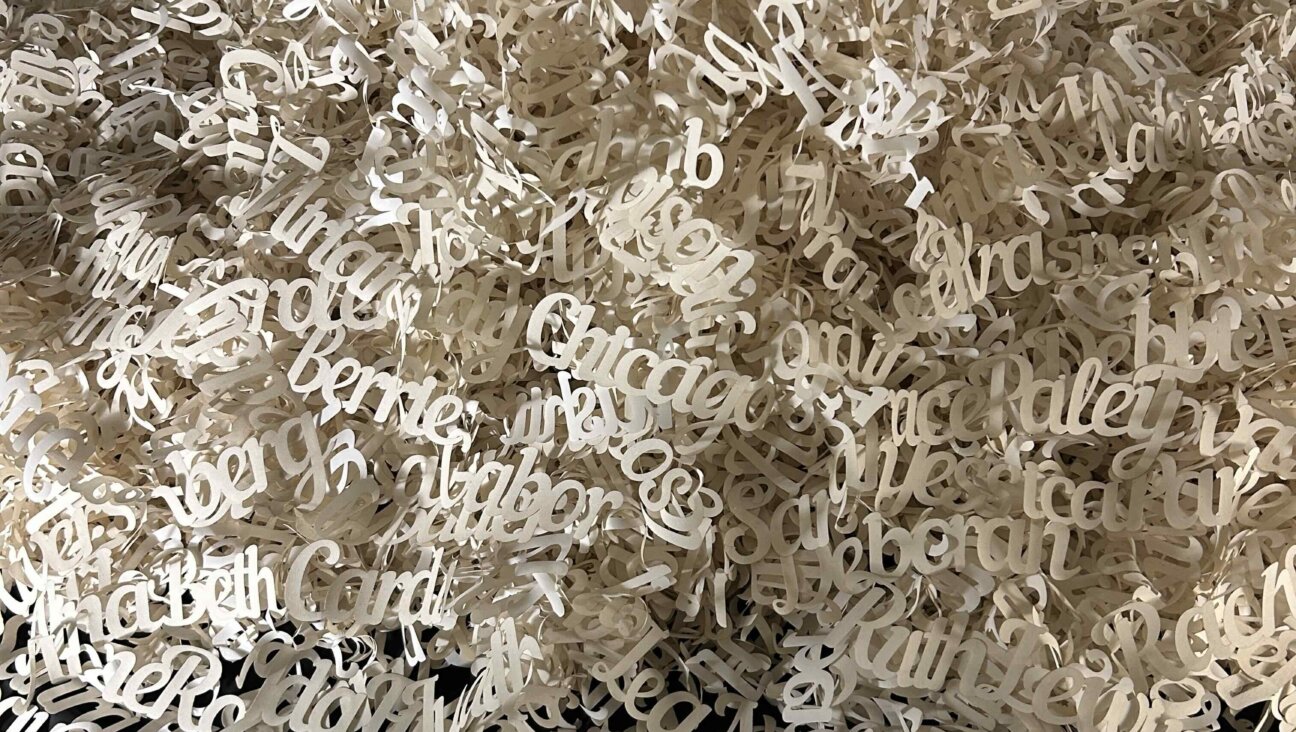

Perhaps Schapiro’s most explicit Jewish-themed statement in art was “Four Matriarchs,” stained glass windows portraying the biblical heroines Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel, and Leah at Temple Sholom, Chicago. In her exuberant, life-enhancing palette of radiant reds, yellows, and blues, Schapiro could seem at times influenced by the precedent of Marc Chagall, also a noted stained glass designer. Like Chagall, Schapiro would leave little telltale symbols in corners of artworks as emotional statements of identity. Her autobiographical quilts, made as part of a lengthy struggle to rehabilitate domestic arts previously considered unworthy of attention, included images of a menorah. In two related canvases, “My History” (1997) and “Lost and Found (1998),” Schapiro likewise displayed menorahs. In the former, a challah cover – the embroidered cloth which is placed over the two loaves on the table on erev Shabbat – is juxtaposed with images of Kahlo, Chagall, and Yellow Stars as worn in Nazi-Occupied Europe, each bearing the word “Jew” in different languages, French, Dutch, and German. In a somber burnished gold, alternating between objects of sacred art and painters who comprised her imaginative family, Schapiro made a strong, celebratory image of selfhood.

“Lost and Found” includes a news photograph of emaciated inmates in a newly liberated concentration camp, much as Paul Brach witnessed. There is also a page from a Hebrew illuminated manuscript and other related objects. In both works, Schapiro includes an energetically dancing couple, as if married companionship were as much a key to her tradition and accomplishment as Judaism itself.

Indeed, although Schapiro long collaborated with such radical feminist artists as Judy Chicago (born Judith Sylvia Cohen in Chicago in 1939), Schapiro never lost sight of the fact that she was a happily married painter. In her painting “I’m Dancin’ as Fast as I Can” (1984), amid bright Chagall-esque colors, Schapiro is represented surrounded protectively by her parents in a recollection of girlhood dance lessons. Few, if any, painters have created a more exultant autobiography of a Jewish woman’s life than Miriam Schapiro.

Benjamin Ivry is a frequent contributor to the Forward.

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning journalism this Passover.

In this age of misinformation, our work is needed like never before. We report on the news that matters most to American Jews, driven by truth, not ideology.

At a time when newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall. That means for the first time in our 126-year history, Forward journalism is free to everyone, everywhere. With an ongoing war, rising antisemitism, and a flood of disinformation that may affect the upcoming election, we believe that free and open access to Jewish journalism is imperative.

Readers like you make it all possible. Right now, we’re in the middle of our Passover Pledge Drive and we still need 300 people to step up and make a gift to sustain our trustworthy, independent journalism.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Join our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Only 300 more gifts needed by April 30