Diaspora Jews Have No Right to Impose Our Policy Preferences on Israel

Image by Getty Images

Earlier this month, The Forward published an article by Daniel Yadin entitled “Why Diaspora Jews Must Call Out Israeli Injustice.” Yadin’s narrative is increasingly popular among frustrated Jews living in the United States, and to be honest I see the appeal. On most issues, Yadin and I are probably in agreement— I disagree strongly with Likud’s settlement policy and disagree with Prime Minister Netanyahu on most matters. But Diaspora Jews are not entitled to dictate to Israelis what is and is not just, and we have a responsibility to resist the temptation to try.

Diaspora and Israeli Jews do share a history, but not a contemporary reality. Israelis’ right to vote in their own elections and decide their own national destiny is derived not from Jewish history but from Israelis’ fulfillment of the duties of citizenship. Most Israelis serve in the military and pay taxes to the Israeli state. They contribute to Israeli culture and the Israeli economy through their daily activities. And they suffer the consequences of their leaders’ decisions, whether that means cowering in bomb shelters or risking their lives to defend the settlement outposts to which Yadin and I are opposed. Diaspora Jews do not live that reality, and therefore do not have a right to make policy for Israel.

Moreover, the idea that Diaspora Jews, and especially Jews in America, have a right to interfere in Israeli political and court decisions comes from a very problematic culture of American exceptionalism and imperialism. The tendency of the majority-Ashkenazi population of Jews in America to criticize Israel began to take serious hold in the 1980s, as Israeli demographics and politics shifted so that Mizrahi and Sephardi Jews began to have a real voice in Israeli affairs. Jews in America were seeing themselves more and more as Western, and Israeli Jews were seeing themselves more and more as part of the fabric of Southwest Asia. Parties like Likud, which depends on a significant Mizrahi and Sephardi voter base, tend to steer Israel away from the “West” and toward its neighbors – they support more conflation of religion and state, a more defensive foreign policy, etc. While I disagree with those policies, I also recognize that my inclination to tell Israelis what to do comes from my upbringing in a problematic American culture that generally regards the US as morally superior and entitled to dictate policy in Southwest Asian countries and all over the post-colonial world. Our communal Ashkenazi (although not all Jews in the United States are Ashkenazi, nearly 90% are) and American privilege, as well as our relative communal wealth (although Jews in America come from a range of socioeconomic backgrounds), gives many American Jews a false sense of entitlement in our relationship with the less collectively wealthy, majority-Mizrahi/Sephardi Israeli community.

Another point that Yadin made in his article is that, in his view, Jews cannot be accused of anti-Semitism. He fails, however, to take into account the influence of structural and internalized anti-Semitism on the ways in which Jews in the Diaspora see ourselves and Israel. Even without believing anti-Semitic myths, we are constantly influenced by the double standards of American society, by the excessive media focus on and bias against Israel, and by the pressures that many of us constantly feel to prove our devotion to the American left by embracing its most unsavory, anti-Zionist elements. The structural anti-Semitism that does exist in American society has taught us that Israel is uniquely evil, and whether we are Jewish or not we are influenced by those ideas. Thus Jews often do express internalized and structural anti-Semitism, and Israelis are right to be wary of anti-Semitism even when in communication with Jews in the Diaspora.

Finally, the American Jewish community’s attempts to strong-arm Israel into fitting our mold of justice, in practice, drive Israel further from our ideal. Historically, a positive relationship between Israel and the United States has been the path to peace. Under the presidency of Bill Clinton, whom Israelis by and large regarded as very friendly, Israel was able to sign a peace treaty with Jordan and to take a major step forward in negotiations with the Palestinians at Oslo. Under the George W. Bush presidency, Israel took the enormous risk of evacuating the Gaza Strip. The peace process has ground to a halt in the last few years with the increase of public friction between the American and Israeli governments. The majority of Israelis support a two-state solution, which would entail the end of the occupation, but they need to be certain of their safety if their gestures for peace are not reciprocated. If the American Jewish community abandons them and America does not respect their concerns, they are much less likely to take the risks necessary for a final peace agreement. For that reason, anyone truly committed to justice and peace in Israel and Palestine ought to dedicate themselves to pragmatic advocacy for a stronger US-Israel relationship.

We Jews in the Diaspora do not have a right to dictate Israeli policy. Despite our shared history, Israeli Jews have a personal stake in Israel’s policy and court decisions that we cannot claim. Our inclination to impose our will on Israel is an outgrowth of our upbringing in a society that teaches American exceptionalism and holds Israel to a double standard. Ultimately, that inclination is neither right nor helpful to the peace process. I disagree with much of what Israel does, but I know that it is not my place to intervene in Israeli politics.

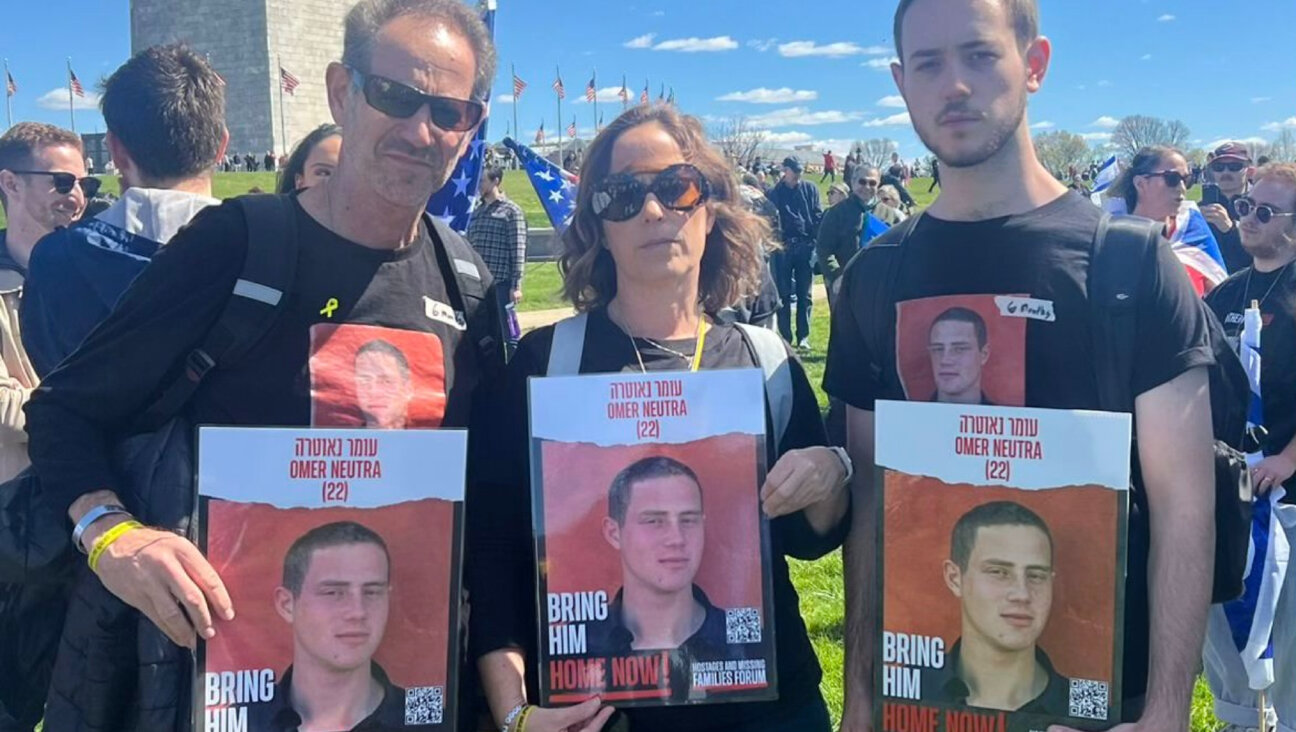

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning journalism this Passover.

In this age of misinformation, our work is needed like never before. We report on the news that matters most to American Jews, driven by truth, not ideology.

At a time when newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall. That means for the first time in our 126-year history, Forward journalism is free to everyone, everywhere. With an ongoing war, rising antisemitism, and a flood of disinformation that may affect the upcoming election, we believe that free and open access to Jewish journalism is imperative.

Readers like you make it all possible. Right now, we’re in the middle of our Passover Pledge Drive and we need 500 people to step up and make a gift to sustain our trustworthy, independent journalism.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Join our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Our Goal: 500 gifts during our Passover Pledge Drive!