Wearing Europe’s Tattoo

An American Great: Cynthia Ozick acts on her ambition. Image by NANCy CRAMPTON

Foreign Bodies

By Cynthia Ozick

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 272 pages, $26

Cynthia Ozick is one of America’s greatest living writers. What makes her work breathtaking is its unvarying subject, a single idea that encompasses all that marks American life, Jewish tradition and every other challenge to the world as it is: ambition. From ancient times, the desire to change the world, or even merely to change one’s life, was what distinguished Israel from other nations. But Ozick understands that ambition as we now know it is actually a form of idolatry, a worshipping of fame and approval over integrity. What makes her work not merely breathtaking, but also necessary, is her awareness of ambition’s opposite: freedom.

An American Great: Cynthia Ozick acts on her ambition. Image by NANCy CRAMPTON

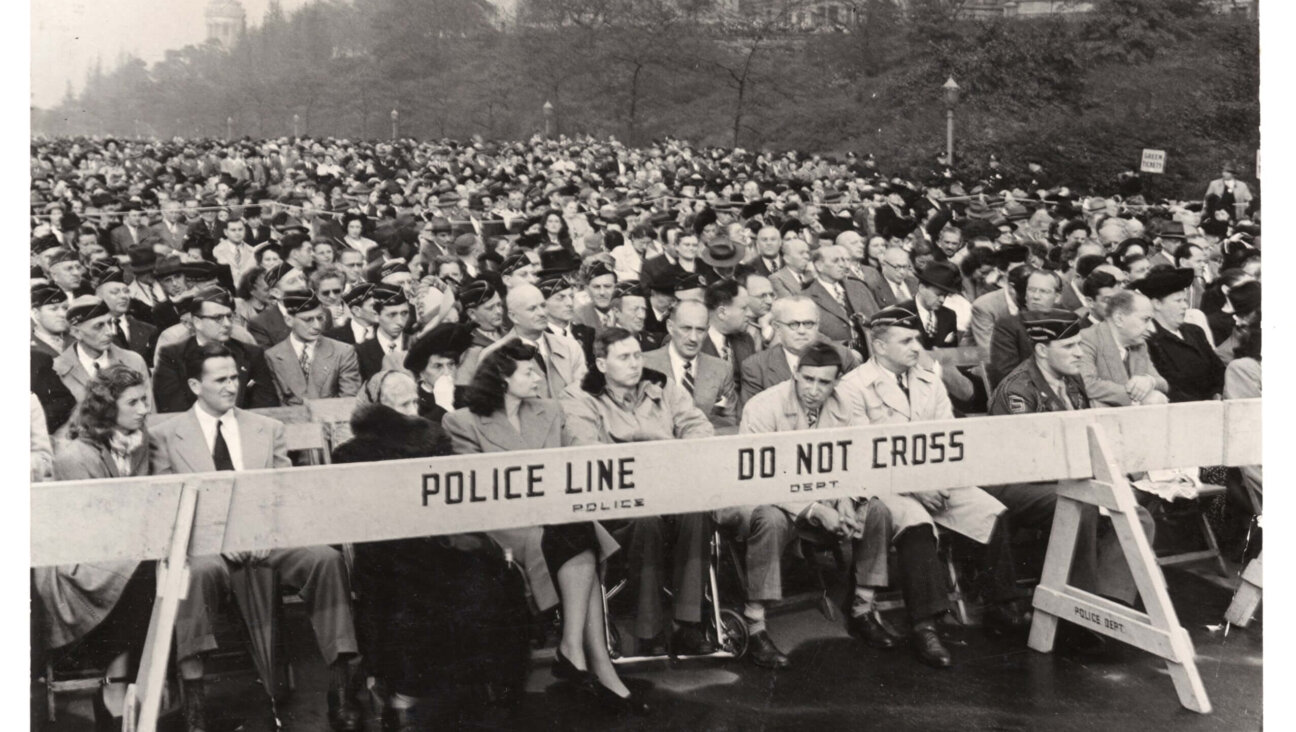

Ozick’s new novel, “Foreign Bodies,” is billed as a “photographic negative” of Henry James’s “The Ambassadors,” using the same plot, but reversing its meaning. When James published “The Ambassadors” in 1903, Europe was the presumed paragon of high culture — and high culture was assumed to confer moral worth. “Foreign Bodies” inverts this assumption completely by unfolding in a very different Europe: Paris of 1952, where callow young Americans imagine that they are a profound avant-garde, and where the city’s natives pretend not to notice the thousands of refugees who, in a phrase that tucks a burning moral judgment into three words, “wore Europe’s tattoo.”

The reader enters this morass through Bea Nightingale (nee Nachtigall), a middle-aged American Jewish teacher whose rich brother sends her to Paris to convince his wastrel son, Julian, to return home. Characters like Bea are conventionally used in fiction to represent lost potential. Childless, Bea is divorced from a composer who left her for Hollywood — and while she excels in teaching, her status as an English teacher at a vocational high school is comically low. But the events that follow ultimately force the question of what it means for a life to have significance. “I want to make my mark,” a naive and poetically inclined Bea had told her husband, and Ozick dissects it: “The trouble with liking poetry… was that it inflamed you, it made you want your life on this round earth to count…. A mark, a mark, a dent in history, a leaving — even (even!) if not her own.”

By the end of the book, that mark is no dream. The “leaving” — of parents, of a spouse, of a child, of a family, of a country, of a continent, of all we thought our lives were for — follows every character through this brilliant story of how we mark others without knowing it, revealing how we are all tattooed by other people’s ambitions.

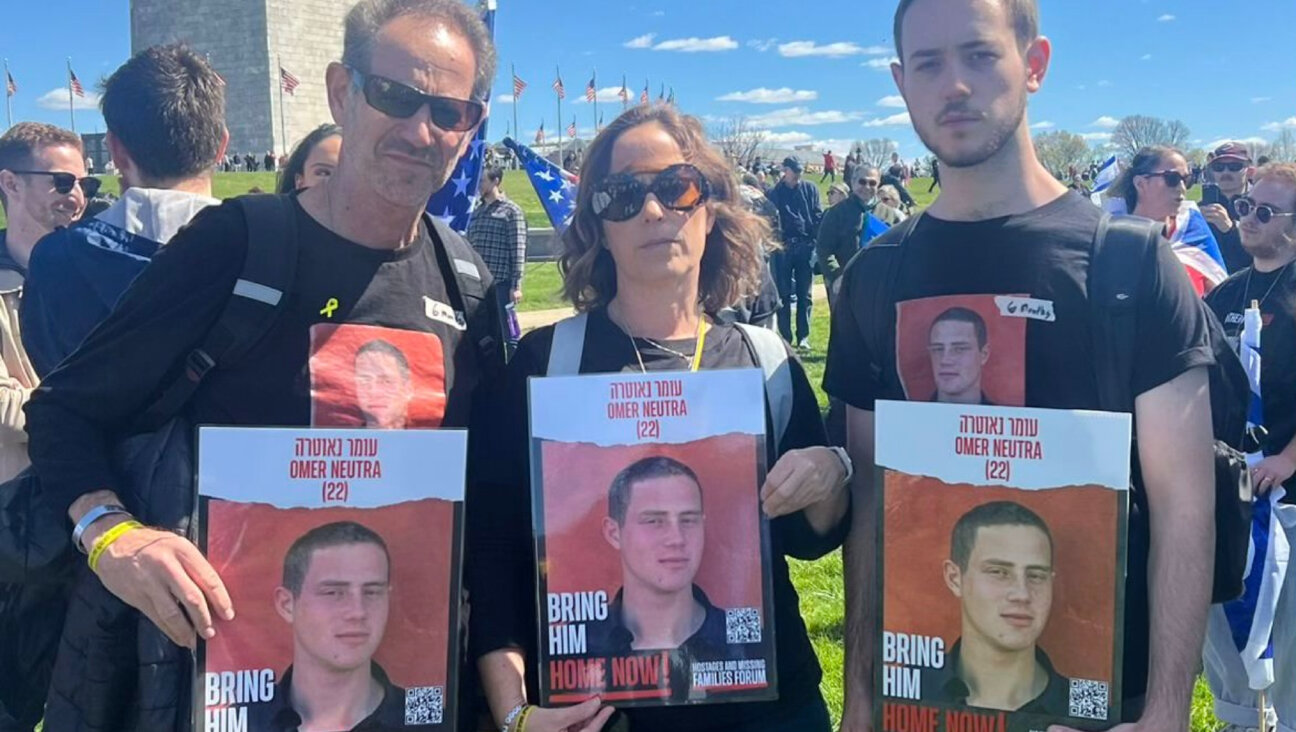

When Bea tracks down her nephew, she finds him involved with a woman 10 years his senior. But instead of James’s Parisian sophisticates, Ozick’s worldly woman is a Romanian Jewish survivor who witnessed the murder of her husband and her child — and who perceives in the immature Julian a full-grown lover, like her husband, as well as a child requiring her care. For Bea’s intermarried brother, Marvin, who has clawed his way to the top of 1950s American society by disdaining his Jewish past, Julian’s shacking up with a Jewish refugee represents the destruction of all his ambitions.

When Julian proves unresponsive to Bea as Marvin’s ambassador, Marvin sends Julian’s sister, Iris, a hardworking chemistry student and sheltered soul, off to Paris to redeem him — only to find that Iris, too, becomes enamored of Paris’s hedonism and then, after many mistakes, enamored of Bea, whom she recognizes as someone whose choices have endowed her with an unexpected freedom. This isn’t the freedom of childlessness or singledom; sociology doesn’t interest Ozick. What interests her instead is each character’s capacity to surprise others into, as one character puts it, “a widening world.”

The page-turning plot of this book is convincing and compelling, enticing us into the story through Ozick’s acute ability to sharpen her characters to a figurative point. As Julian’s refusal to return home forces more characters out of their ordinary lives, we follow them through seductions, abortions, deaths, scandals, vengeances and revelations about their pasts and futures, all entirely believable.

As Bea unburdens herself from her own encounter with artistic ambition (embodied by her talented and cruel ex-husband), her calculated choices affect the other characters in profound, unexpected and completely plausible ways, all pointing to the questions of how and why we want more than life offers us — questions that are answered, vividly and wonderfully, in the surprising and perfect symmetry that ends the story. It’s the kind of book you want to read twice.

Ozick’s oeuvre is driven by the idea of ambition, and the same might be said of Ozick herself. She has frequently written about how artists, including herself, experience envy for those more popular. The countless accolades she has received often seem not to have sated her hunger for wider acclaim — or, more important, her yearning for a culture in which an enduring talent like hers would be as lauded as the latest flash in the pan. But in this novel, one can see, for the first time in Ozick’s fiction, the ultimate and absolute victory of personal devotion over personal ambition. Near the novel’s end, Bea arrives at a simple revelation: “She thought: How hard it is to change one’s life. And again she thought: How terrifyingly simple to change the lives of others.”

As one of the many readers whose life has been indelibly marked by Ozick’s words, I can only agree.

Dara Horn is a Forward contributing editor. Her most recent novel, “All Other Nights” (W.W. Norton & Company, 2009), is about Jewish spies during the Civil War.

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning journalism this Passover.

In this age of misinformation, our work is needed like never before. We report on the news that matters most to American Jews, driven by truth, not ideology.

At a time when newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall. That means for the first time in our 126-year history, Forward journalism is free to everyone, everywhere. With an ongoing war, rising antisemitism, and a flood of disinformation that may affect the upcoming election, we believe that free and open access to Jewish journalism is imperative.

Readers like you make it all possible. Right now, we’re in the middle of our Passover Pledge Drive and we need 500 people to step up and make a gift to sustain our trustworthy, independent journalism.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Join our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Our Goal: 500 gifts during our Passover Pledge Drive!