‘Shtisel’ Fills a Void in Israeli Television

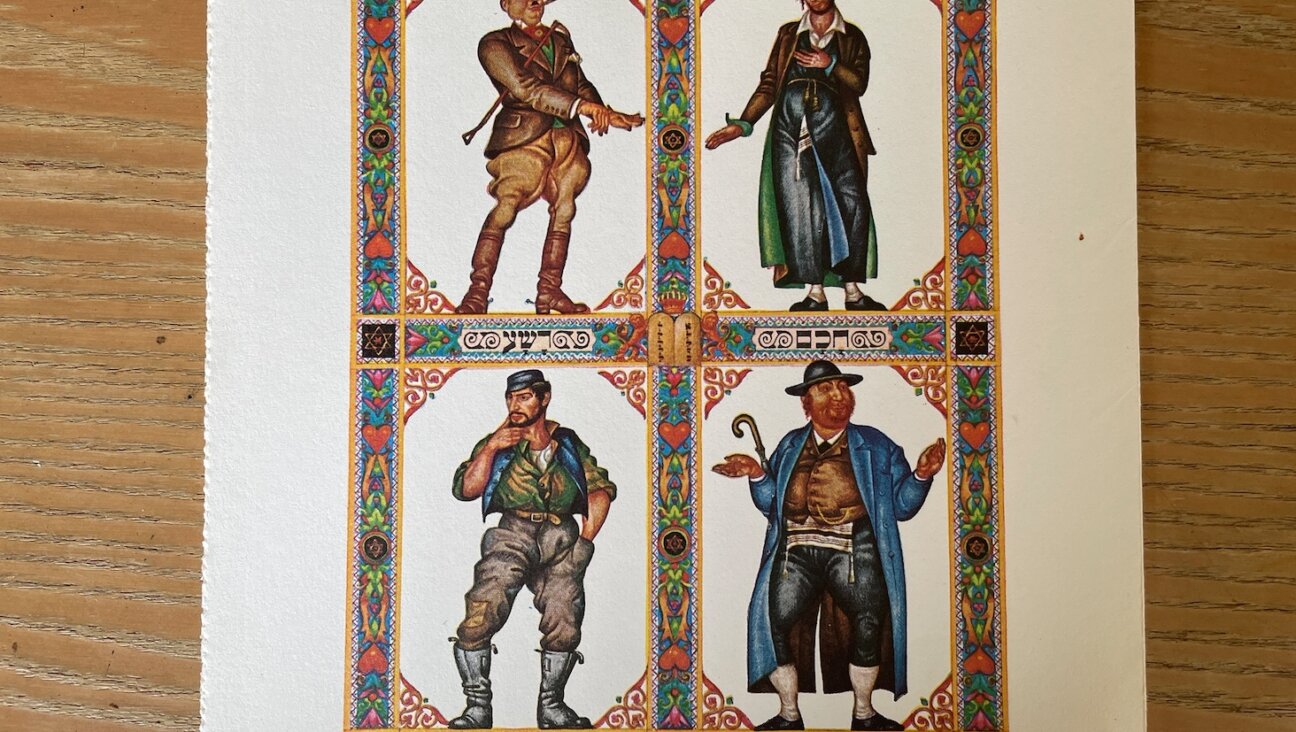

Little House in Jerusalem: Neta Riskin and Shira Hass play a mother and daughter in the TV series ?Shtisel.? Image by Roey Roth

The creators of the new hit Israeli Hebrew-language TV drama series “Shtisel,” which debuted earlier this summer on the YES cable channel, are pleased by the series’s popularity; however, they say they are not surprised by it.

The unique appeal of “Shtisel” is as much about what it is not as it is about what it is. The series is a story of a Haredi family living in Jerusalem’s ultra-religious Mea Shearim neighborhood. But it’s not a story about the constrictions of Haredi life. Unlike most Israeli films and television shows with Orthodox characters, religious life is not a central tension point in the narrative. None of the characters rages against or is looking to leave his or her life circumscribed by ancient Jewish law and custom.

No detail is overlooked in fully realizing the Haredi setting, but at the same time, the accurate portrayal of ultra-Orthodox home, work, school and street life is almost beside the point. What’s got viewers in Israel and abroad glued to their televisions on Saturday nights and computers the next day, when the links to the latest episodes are posted online, are the series’s poignantly written, excellently acted and resonant storylines about life, love and loss.

“I enjoy watching “Shtisel” because it shows another side of the Haredi community, which is not often reflected in the news or in popular depictions of their world — a side in which the Haredim are portrayed as people with all the emotional struggles and difficulties as their secular counterparts,” said viewer Yosef Weinstock, a secular Israeli from Herzliya.

Adina Kischel, a Modern Orthodox viewer from Ma’ale Adumim, says she is hooked for the same reason. “The characters are watchable and interesting, with personal doubts and questions people from other worlds can identify with,” she said. “I want to get to know these characters, find out what happens to them and understand why they do what they do. I can buy into their stories and motivations.”

Well before “Shtisel” hit the airwaves, its quality was apparent to funders. “The stories and character development are truly exceptional,” said Suri Drucker, director of the Avi Chai Foundation’s Film & Television Project,which together with the Gesher Multicultural Film Fund invested $90,000 in producing the series.

“We can all identify with these characters no matter what our backgrounds are. They cross cultures. That’s what we look for when we are approached with a script,” Drucker said. “A good story must portray Jewish life in an engaging, nonapologetic, humanly complex manner.”

The show focuses on the extended Shtisel family (writers Yehonatan Indursky and Ori Elon borrowed the name from a restaurant frequented by Jerusalem’s Haredim), but there are many characters and plot lines. The main narratives involve patriarch Shulem’s adjustment to life after his wife’s death, and his forced retirement from teaching at a local Talmud Torah; eldest daughter Gitti’s attempts to cope after her husband abandoned her and their children, and youngest and artistic son Akiva’s strategies for dealing with pressure to find a suitable marriage, all the while longing for Elisheva, a twice-widowed young mother wary of giving herself over yet again to love and marriage.

There is undoubtedly a whiff of melodrama about the series; however, it never actually devolves into a soap opera. The first season’s 12 episodes are woven together almost as seamlessly as a full-length feature film.

“This series is very cinematic,” said producer Dikla Barkai, who also produced the hit series “Srugim” about young Modern Orthodox Jerusalemites. “It was written that way. It’s a contemporary television series, but it plays like a period piece.” With the many shooting locations involved, the myriad supporting actors and extras (including many children), and the attention paid to setting detail, Barkai says there was no other way to approach the project.

Barkai and her producing partners chose movie director Alon Zingman to direct. Zingman, in turn, brought along Roey Roth, the cinematographer who worked with him on his 2010 film, “Dusk.”

“I was chosen to give a cinematic look to ‘Shtisel,’” said Zingman, who had no prior television experience. Moved by Indursky and Elon’s script, which was spiced with poetic language and magical realism, the director took up the challenge — soon learning just how big a challenge it was.

On the first day of filming, the crew was chased out of Mea Shearim by Haredim who were incensed by the sight of a female crewmember applying makeup to a male actor. This convinced Zingman that he would have to go stealth.

From then on, he brought into the neighborhood only a small all-male crew dressed in Haredi garb. “We also used a hidden camera and shot scenes of actors outside in the street from inside buildings,” Zingman said. “We were worried that people would discover that some of the actors were wearing fake beards, or would wonder why they appeared to be talking to themselves while taking direction from me through earpieces.”

It wasn’t just the guerilla filming that was new to Zingman. “Every aspect of this production was challenging to me,” he said. “I came into this completely unfamiliar with the Haredi world. I think we undertook the widest and most intensive research ever undertaken for an Israeli TV drama.”

While Indursky grew up in a Haredi family (his 2012 documentary “Ponevezh Time” was inspired by his own years at the famous Ponevezh Yeshiva in Bnei Brak) and Elon was close to his ultra-Orthodox grandparents, everyone else needed to attend a Haredi boot camp of sorts. Zingman and the actors took Yiddish lessons so that they would be able to understand and properly pronounce the significant amounts of Yiddish dialogue. They also spent the Sabbath with families in Mea Shearim, eating meals and going to synagogue with them.

Members of the mainly young, secular production team also did their own research, relying on the insights and guidance of several people involved in the Haredi film industry. These people served as consultants and fixers prior to and during the series’s shooting from late summer through fall of 2012.

Ayelet Zurer, who plays Elisheva, wasn’t able to join the rest of the group for these immersive preparatory experiences. Having lived for the past seven years in Los Angeles, her commitments as a Hollywood actress (most recently playing Superman’s biological mother in this summer’s blockbuster, “Man of Steel,”) necessitated her arriving in Israel only toward the end of the production schedule.

“She’s very different from any character I have ever played,” Zurer said of Elisheva. “I’m happy I did this. It let me see that religious people are not that different from me.” She added that she felt particularly attracted to the character’s repressed rebellious nature. “Deep inside she doesn’t really fit in,” she added.

As Elisheva’s love interest, Akiva also finds himself somewhat on the margins of Haredi society. While the thought of leaving the ultra-Orthodox way of life never occurs to either of them, it’s clear that they do not fall completely within their community’s mainstream.

Indursky said Elisheva and Akiva’s dash of outsider-ness is a nod toward compelling storytelling. “There are always more opportunities for interesting meetings to take place on the margins…. A rabbi once said, ‘Horses walk in the middle of the street, people on the sides.’”

Shtisel will be distributed (with English subtitles) in North America by Go2Films.

Renee Ghert-Zand is a freelance writer covering Israel and the Jewish world for the Forward and other publications.

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning journalism this Passover.

In this age of misinformation, our work is needed like never before. We report on the news that matters most to American Jews, driven by truth, not ideology.

At a time when newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall. That means for the first time in our 126-year history, Forward journalism is free to everyone, everywhere. With an ongoing war, rising antisemitism, and a flood of disinformation that may affect the upcoming election, we believe that free and open access to Jewish journalism is imperative.

Readers like you make it all possible. Right now, we’re in the middle of our Passover Pledge Drive and we still need 300 people to step up and make a gift to sustain our trustworthy, independent journalism.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Join our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Only 300 more gifts needed by April 30