Continuing Their Mission, Jewish Hospitals Reinvest in Philanthropy

HEALING POWERS: Manhattan?s Beth Israel Hospial, in 1928.

In eight American cities, there are grant-making foundations created from the sale of Jewish hospitals, with combined assets in excess of $1 billion. For American Jewry, these foundations are the most important legacy of the Jewish hospital movement, one of American history’s most ambitious undertakings in Jewish philanthropy.

HEALING POWERS: Manhattan?s Beth Israel Hospial, in 1928.

Between 1850 and 1955, Jewish communities in 24 American cities founded general acute-care hospitals. With names like “Jewish Hospital,” “Mount Sinai” and “Beth Israel,” these institutions were often the local Jewish community’s most visible and impressive charitable enterprise. These hospitals’ first task, of course, was to provide care and comfort to sick Jewish patients, especially immigrants and indigents. Their larger mission was to help make America a more hospitable place for Jews by combating anti-Jewish stereotypes and hostility, and providing enclaves from anti-Jewish discrimination.

The decline of antisemitism in the United States since World War II obviated most of the problems that Jewish hospitals were founded to address. Since the mid-1980s, changes in the American health care system pressured most Jewish hospitals outside New York City to either merge with large health care systems or be sold to them. In the cases of sale, the proceeds were used to endow grant-making foundations that support a wide range of charitable projects, including some designed to benefit American Jews. In those instances, the Jewish community has effectively recaptured some of the wealth tied up in Jewish hospitals and reapplied it to address its more pressing problems.

The first Jewish hospitals in the United States were The Jewish Hospital in Cincinnati (1850) and The Jews’ Hospital in New York City (1855). Although they provided modest treatments at best, they met their Jewish patients’ distinct religious and cultural needs and shielded these patients from Christian proselytizers. Jewish hospitals also served broader Jewish interests by improving community relations. By diverting sick and poor Jews from non-Jewish sources of aid, Jewish hospitals helped respond to complaints that Jewish paupers burdened the larger society. And by adopting nonsectarian intake policies, these hospitals challenged stereotypes that Jews were clannish people who took care of only “their own.” In fact, in 1866, to underscore its open-admissions policy, The Jews’ Hospital changed its name to The Mount Sinai Hospital; it still operates today.

Jewish hospitals also mitigated the anti-Jewish discrimination that pervaded the medical establishment after World War I. They provided Jews with opportunities that were otherwise unavailable: residencies that enabled Jewish medical school graduates to specialize, staff privileges that enabled Jewish physicians to treat patients in hospitals, and leadership positions for Jewish philanthropists to demonstrate civic virtue and socialize with other elites.

As antisemitism in the United States receded in the 1960s and ’70s, American Jews came to see Jewish hospitals as increasingly marginal to their concerns and wasteful of their resources. As Jews became more assimilated, fewer Jewish patients had distinct needs, and more non-Jewish hospitals were willing to accommodate those who had these needs. (In 1962, the first non-Jewish hospital, a Catholic hospital in Reading, Pa., installed a kosher kitchen.) Soon, Jews — whether they were medical school graduates, practicing physicians or philanthropists — were given more opportunities from non-Jewish hospitals. Jewish hospitals, for their part, also became less demonstrably Jewish. Most were serving more non-Jewish patients than Jewish ones, offering pork products in their cafeterias and putting up Christmas decorations. As they earned more revenue from commercial insurance and public programs, they had less need for Jewish philanthropic support. In 1968, for example, Jewish hospitals received only 1.7% of their revenue from Jewish umbrella funds or federations. For their part, Jewish federations ultimately redirected resources to deal with more pressing matters, such as Jewish continuity. From 1920 to 1960, Jewish federations allocated about 25% of their local grants to Jewish hospitals. By 1981 they allocated more than 25% to Jewish education and less than 3% to hospitals.

What kept Jewish hospitals institutionally “Jewish” was the predominance of Jews on their boards of directors. Because successor directors chosen by these self-perpetuating boards were predominantly Jewish, these institutions might have stayed Jewish indefinitely. In the end, however, it was not assimilation or integration that sealed the fate of Jewish hospitals; it was economics. The Reagan administration changed Medicare regulations, and these were instrumental in prompting some changes in the health insurance industry. In this new environment, large for-profit entities were enticed to enter the industry and many smaller hospitals were impelled to consolidate. These trends put the squeeze on independent community-based hospitals — a class that included all Jewish hospitals.

In response to these changes, a half-dozen or so Jewish hospitals outside New York (which is sui generis) merged with non-Jewish systems. This move made these hospitals more competitive but took away control from the local Jewish communities. Formerly independent Jewish hospitals in Boston; Louisville, Ky., and St. Louis are now subsumed within Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Jewish Hospital & St. Mary’s HealthCare and Barnes-Jewish-Christian HealthCare, respectively.

Other Jewish hospitals tried to remain both competitive and Jewish by finding a niche and forming their own systems. Mount Sinai in Miami represents one type of contemporary Jewish hospital: It serves a substantial number of observant Jews and meets their religious needs and cultural sensitivities. Mount Sinai in Chicago is another, serving mostly poor African American and Hispanic individuals from the surrounding neighborhood, Lawndale, which once housed Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. The hospital remains connected to Chicago’s Jewish community through Jewish directors, donors, physicians and volunteers, and through its affiliation with Chicago’s Jewish federation, which provides grants and loan guarantees and lobbies on its behalf for more public support.

A third type of Jewish hospital purports to honor its Jewish origins through excellence in teaching and research. (In other cases, however, directors saw mergers with non-Jewish systems as a means to maintain first-rate training and research programs. In the end, they decided it was more important for their institution to be excellent than to be Jewish.)

The majority of formerly Jewish hospitals outside New York — eight in all — were sold to other health care systems, and the proceeds of these sales were used to endow grant-making foundations. Their combined assets of more than $1 billion represent almost 5% of the total assets of all foundations formed from the sale of not-for-profit hospitals. All these foundations make at least some grants to Jewish organizations and causes. Most concentrate their Jewish grant-making on the health and human services needs of elderly Jews, recent immigrants from the former Soviet Union, people with disabilities, Holocaust survivors, and other vulnerable and underserved Jewish populations. Yet the largest, most daring and farsighted of these grant-makers, Rose Community Foundation in Denver, focuses its Jewish giving on communal life rather than on the health of Jewish individuals. According to its literature, Rose Community Foundation supports “efforts to create and sustain a vibrant Jewish community,” especially through “outreach to unconnected Jews, [and] experiences that promote Jewish growth, leadership development and organizational development.” This entails, among other things, grants to Jewish studies programs and student organizations at universities; Jewish youth groups; festivals and conferences that celebrate Jewish learning and culture; Judaism 101 classes; a “Shalom Baby” program for families with newborns, and special programs for intermarried couples and children of interfaith marriages.

Most of these foundations direct the bulk of their giving to non-Jewish organizations and causes. Such grant-making may indirectly serve Jewish interests by generating good will toward the Jewish community. This is especially true of those foundations that publicize their origins in the Jewish community, such as the Jewish Healthcare Foundation of Pittsburgh, the Jewish Heritage Foundation of Greater Kansas City, The Jewish Fund of Detroit and the Healthcare Foundation of New Jersey, which bills itself as “Founded by the Jewish Community” of Newark.

The denouement of Jewish hospitals offers a lesson for future Jewish philanthropic enterprises: Founders should consider how — should an enterprise’s value to the Jewish future decline — its resources might be recouped and reinvested in ways more useful to the community.

An expanded version of this article can be downloaded here.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

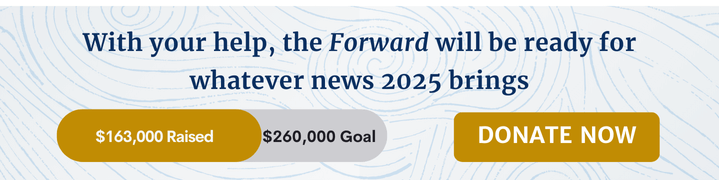

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO