How I converted to Yiddish

A former Catholic schoolboy in Memphis, Tennessee, describes how Yiddish became an important part of his life.

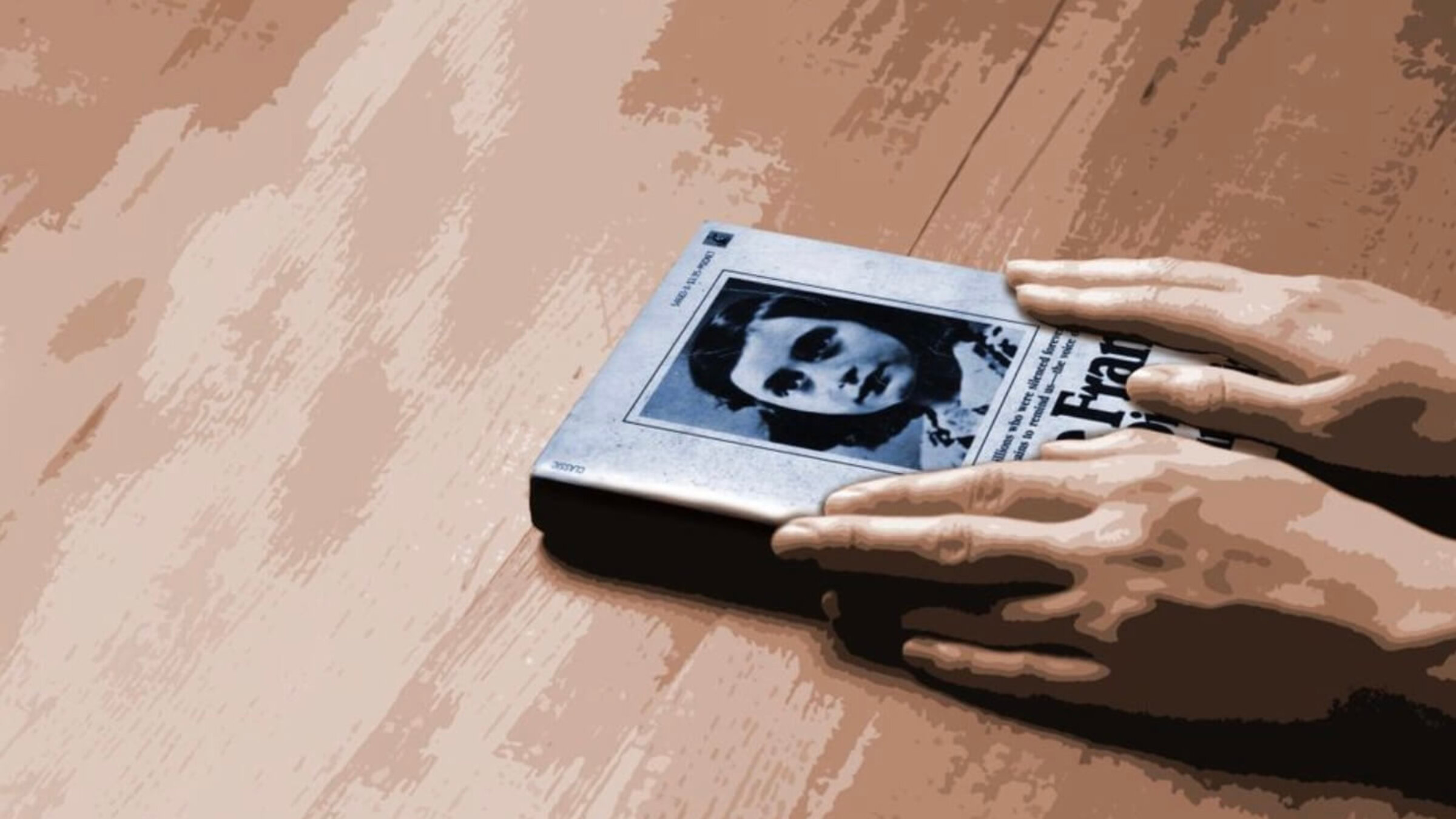

Image by Nikki Casey

People often ask me: “What made you want to learn Yiddish if you aren’t even Jewish? Why convert to Judaism, when we, Jews, have so much trouble?” It’s hard for me to give a simple answer that summarizes my love for the Yiddish language or my eagerness to bond with the Jewish people.

I was born in Memphis, Tennessee, and come from a typical Italian family. I attended Catholic school. Although my parents are Catholic, they aren’t very religious. We always lived among Christians and I never had any Jewish friends or acquaintances.

My interest in Jews began in sixth grade when we read Anne Frank’s “The Diary of a Young Girl” and learned about the persecution of the Jews during the Holocaust. I found myself identifying strongly with this Jewish girl. She had to hide from the Germans because she was Jewish, and I had to hide from everyone because by then I knew I was gay. The Germans and other nations hated the Jews simply because they were born Jews, and I worried that if people discovered my secret, I’d be hated too.

I became very curious about Jewish culture and history, especially what transpired during World War II. I read memoirs of Holocaust survivors, and that’s when I learned about the Yiddish language, about life in the shtetls of Eastern Europe and about the Jewish religion and traditions.

That same year, while I was on vacation with my family in Chattanooga, Tennessee, I noticed a small synagogue behind our hotel. I asked my mother if I could go there on “the Jewish Sabbath”

“Of course,” she replied. That Friday, she brought me to the rabbi to ask if I could go to the synagogue the next day, and he welcomed me warmly.

On Shabbos morning, I entered the synagogue, donned a yarmulke and sat in the back. Although I couldn’t read a single letter of the Hebrew prayers, I moved my lips, pretending I knew how.

Several years later, I started going to a Catholic high school for boys, run by monks. During the second year, everyone studied the “Hebrew Testament.”

On the first day of class, our teacher surprised us. “Gentlemen,” he said, “this year we’ll be studying the Hebrew Testament. Notice I didn’t say the ‘Old’ Testament. The reason? That would be insulting to our Jewish brothers and sisters. When we say the ‘Old’ Testament, we’re implying that we believe it to be out of date and no longer valid. So out of respect for the Jewish people, I want you all to call the Jewish Bible the Hebrew Testament. And I’m going to actually teach you the Hebrew alphabet and how to read parts of the Bible in Hebrew.”

He ended his speech with a confession: “If I hadn’t become a priest, I probably would have become a rabbi.”

I loved Hebrew. It brought me closer to Judaism and came in handy later when I began studying Yiddish. At the end of the year, I won the prize for being the best Hebrew student in class: a white figurine of Moses holding the Ten Commandments — the inscription was written, of course, in Hebrew.

Following high school, I spent about 10 years in foreign countries —Brazil, Italy and Spain — all of them having very small Jewish populations. When I returned to Memphis, I started thinking again about learning more about the Jews, and about Yiddish too.

I bought the standard dictionary by Uriel Weinreich and a couple of Yiddish textbooks, and made an effort to learn the language on my own. I even downloaded a Yiddish book from the website of the Yiddish Book Center, “On Both Sides of the Ghetto Wall” by Vladka Feigele Peltel Miedzyrzecki. I had to look up almost every word, and I understood almost none of it.

At the same time, I registered for a “Judaism 101” course at the synagogue, but went only a couple of times. It just didn’t make sense for me since I still didn’t know any Jews. I knew that to be Jewish meant to be part of a congregation, and I was still without one.

In 2013, I decided to move to Miami Beach, and this literally changed my life. Finally, I had the opportunity to learn Yiddish and to get closer to Judaism. Corey (Gedalieh) Brier, president of the Yiddish Artists & Friends Actors Club, asked me if I’d like to work with him as a volunteer in a Jewish nursing home. Every Friday night, he and a group of volunteers would go there to usher in Shabbos with the residents. I agreed. I learned the Yiddish songs so that I could sing along. Most moving for me was the Shabbos ceremony itself.

In fact, it was Gedalieh who gave me my Jewish name. When I introduced myself as Mario, he replied: “You’re no Mario, you’re Moishele!” And that’s what I’ve called myself ever since.

Honestly, I wasn’t sure if I really wanted to convert. How could I, having grown up Catholic and being taught all my life to believe in Jesus and Maria? But slowly I began to wonder how important was it really for me to believe in Jesus and Maria when we just need to believe that there’s only one God?

I started going regularly to Temple Israel of Greater Miami – a wonderful, progressive synagogue and very “gay friendly.” In the beginning, I didn’t feel comfortable there, but I continued going every Friday night and met many people. Once I started feeling at home there, my doubts disappeared and I began to prepare me for conversion.

So next month, I’m going to enter Temple Israel with my parents and all my Jewish and non-Jewish friends, and finally, I’ll become a member of the tribe. For me, this will mark the end of a long journey — or maybe just the beginning.

Translated by Paula Goldberg

A version of this story appeared originally in the Yiddish Forverts.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO