Purim in Paris: Rachel Félix and the Paradox of French Anti-Semitism

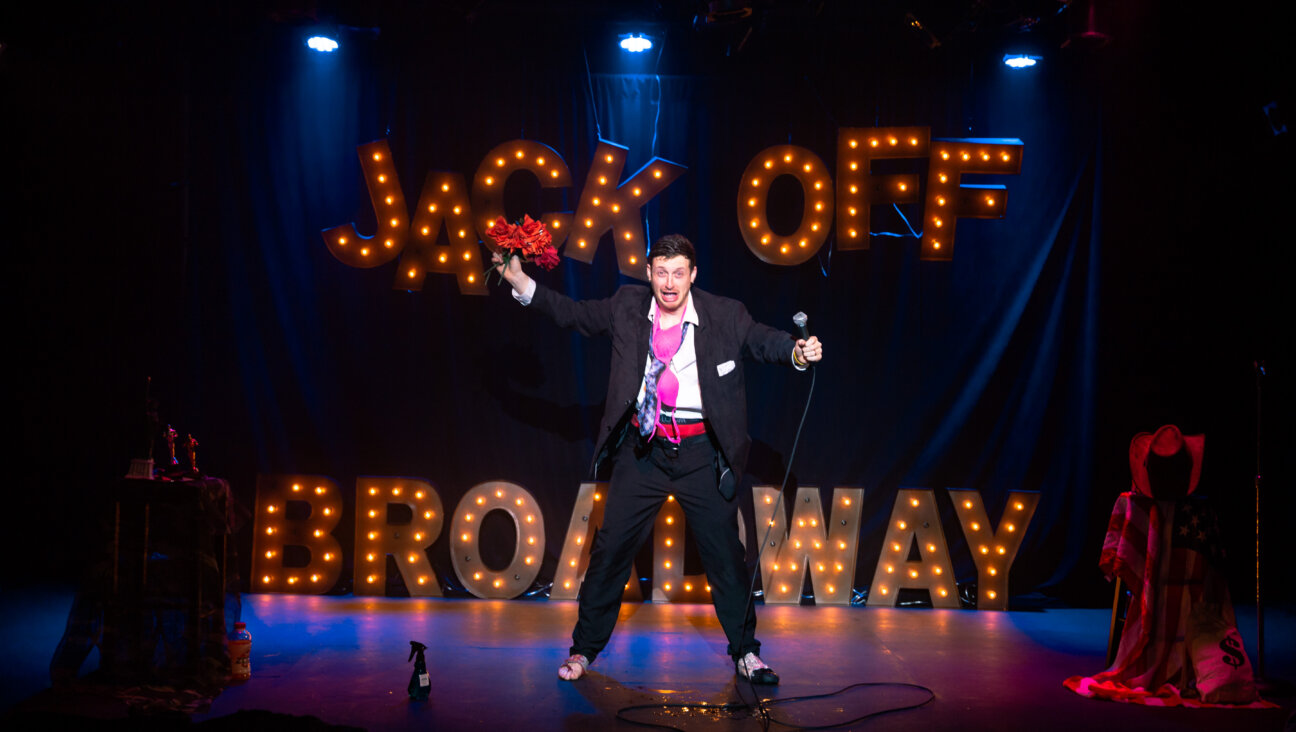

The Comédie Française Image by Getty Images

Paris is crammed with sites of Jewish interest. While some are obvious — the shops on the Rue des Rosiers or the Holocaust memorial at Drancy — others come as more of a surprise. The Comédie-Française belongs to this latter group.

The nation’s oldest state theater, founded in the 17th century under the aegis of Louis XIV, has produced the works of France’s greatest writers, from Molière to Beckett. And on February 28, 1839, the venerable venue hosted a Purim celebration without parallel as Jewish actress Rachel Félix starred as Esther in Jean Racine’s play of the same name.

“Esther” had been staged as a tribute to Félix’s Jewish heritage, and the theater was flooded with spectators desperate to see this limited engagement. Jules Janin, a contemporary theater critic, wrote in a newspaper review that the Comédie had enacted “a serious and solemn celebration” in honor of “this miraculous child, a Jewess.” The mood, he added, had pervaded the entire French capital, which “was given over to an immense celebration, unanimous praise, a torrent of emotions that we will never see in our lifetimes.”

Félix’s story, chronicled in Rachel Brownstein’s “Tragic Muse: Rachel of the Comédie-Française” and in Maurice Samuels’ intellectual history, “The Right to Difference: French Universalism and the Jews,” is not merely an uplifting Purim tale. As France searches its soul over anti-Semitism — which has returned to the headlines amid a surge in hate crimes against Jews — her life and work provide a fuller picture of the country’s long and complicated relationship with its Jewish population.

Felix’s origins did not mark her out as bound for stardom. Born in 1821 to Jacques and Thérèse Félix, itinerant peddlers then on the road in Switzerland, Rachel was the second in a brood of five children who all would appear on the French theater scene. The family was on the move for much of her childhood, and in each town Rachel and her sisters would busk on the streets to supplement the household’s income. Rachel came to the attention of music teacher and Étienne Choron in 1831, when he noticed her sidewalk act in Lyon.

Soon thereafter, the family headed to Paris, where Félix enrolled in Choron’s school and was passed from one tutor and mentor to the next until 1838 when she debuted as an actress of the Comédie-Française under the stage name of “Rachel.” After a summer and fall spent as Pierre Corneille’s Camille, Jean Racine’s Hermione and Voltaire’s Aménaïde, she was acclaimed by Paris’ theater critics as the interpreter par excellence of neoclassical tragedies. According to Brownstein, an English professor at the City University of New York, Félix developed a reputation — and originated a model for a certain kind of actress: “thin, dark, Jewish, nervous, passionate, serious, and maybe a little desperate.”

Neoclassicism, inspired by the stories and authors of Greek and Roman antiquity, was a style that predominated in 17th and 18th century France. The genre contributed much to the prestige of the country’s literary tradition and reflected and reinforced the emergence of modern standard French. Mastering the canon was no simple task: neoclassicism demanded, as Brownstein observed, rigorous formalism in verse, plot and delivery. The action was supposed to occur within the space of 24 hours, all in the same place. Bloodshed was to happen out of sight, in the stage’s wings, and the preferred form of romance was unrealized or unrequited.

Some neoclassical masterpieces were written at the behest of noble patrons and thus bear the fingerprints of the benefactor. Such was the case with “Esther,” commissioned by the wife of Louis XIV, Madame de Maintenon, as a fable for the girls at her convent academy in Saint-Cyr, where she schooled the daughters of poorer noble families. “Esther” was meant to add to the women’s moral education, “instructing them in entertaining them,” as Racine wrote in his preface to the piece.

The tale of Esther is familiar to those of us accustomed to spinning groggers since childhood. King Ahaseurus divorces his wife Vashti after she declines to appear at court. The king then orchestrates an empire-wide beauty contest to find a more pliant spouse. Esther, the provincial belle of exiled Israel, wins the heart of the Persian monarch. She then must grapple with Haman, who, incensed by her uncle Mordechai’s refusal to bow before him, secures the king’s approval for the extermination of the imperium’s Jews. The day is saved when Esther, at Mordechai’s urging, declares her origins before Ahaseurus. He spares her people, Haman hangs on the gallows, and the Israelites kill thousands of their foes in reprisals.

Racine’s “Esther,” penned in 1689, amounts to a lesser work in his repertoire, and as Brownstein wrote, “was taken out of mothballs to be a vehicle for [Félix].” While no “Phèdre” or “Andromaque,” “Esther” did hit all the right notes to herald Félix as the new sovereign of the Comédie-Française. Racine’s play takes a few liberties with the ancient text while in the main hewing close to it. Racine added Elise, a confidante of Esther, who exults in her friend’s good fortune: “The proud Ahaseurus crowns his captive, and the superb Persian is at the feet of a Jewish woman.” He punched up the confrontation between Mordechai and Esther, who fears she will lose all by dropping in on the king unannounced. Though the Book of Esther’s Mordechai uses the language of self-interest to move the queen to act, Racine’s Mordechai appeals to Esther’s sense of solidarity and faith: “Your life, Esther, does it belong to you? Does it not belong to the blood of which you are descended? Is it not God from whom you received it?”

The reader detects the specific needs of Madame de Maintenton’s students in Racine’s addition of a chorus and his omission of the massacre in the coda of the original tale. The chorus expanded the cast so that more students could take part in the production, and the mass murder was presumably excised to spare the desmoiselles such gruesome details. In his preface, Racine also alluded to Purim in a passage that surprises in its failure to condemn modern Jews as perfidious infidels. Defending his ending, in which the Israelites praise God ad nauseum for their triumph, he cited the customs of contemporary Jews: “One even says that still today the Jews celebrate by acts of great thanksgiving the day when their ancestors were delivered by Esther from the cruelty of Haman.”

Samuels, chair of Yale’s French department and director of the university’s Program for the Study of Anti-Semitism, posited that Félix’s stint as Esther can be read as an allegory for the relationship between France and the Jews, the first the magnanimous Persian king and the second the obliging Israelite consort. Ahaseurus raises up Esther to the status of queen and saves her people from a certain death. The French state had emancipated its Jews and then had opened the sanctum of high culture to Félix and her compatriots. Félix’s admission to society came not as a result of subsuming her religious difference into some generic Frenchness, but in inhabiting and even sometimes magnifying her particularity.

Félix was a chimera, a neoclassical thespian disposed in her own life to the overstated and ostentatious, a woman decked out as the virtuous dames of the canon but from whom the whiff of scandal emanated, someone who entertained aristocrats and masses, declaiming somewhere on that remote crossroads where Maria Callas meets Édith Piaf. Having performed the role of Judith, the Biblical femme fatale who saved the Israelites in seducing and then decapitating an enemy general, she exhibited a set of daggers in her Paris home. She also hung from the walls in the same apartment a beaten-up guitar that she claimed had been among her first musical instruments. The capital’s high society could catch a glimpse of these strange embellishments each week as Félix received visitors in her salon. She ran through legions of paramours, several of them relatives or intimates of Napoleon. She was, to quote one Piaf tune, “like the sea, with a heart too big for one man.”

Félix consciously incorporated Jewishness into her life and art. Born as “Élisabeth-Rachel Félix,” “Élisabeth” was unceremoniously lopped off as she entered the theater, supplanted by an unadulterated and plain Hebraic stage name, “Rachel.” She drew attention to her background in anchoring productions of “Esther” and Racine’s other Jewish work, “Bérénice.” Félix’s family presented themselves as observant Jews, but the truth was a bit more complicated. Brownstein noted that the Félix clan probably disregarded kosher laws and that Rachel was to be found at the Comédie on Yom Kippur.

Félix’s admirers also exaggerated her supposed foreignness and exoticism. “Mademoiselle Rachel is a Jewess,” wrote critic Antoine de Latour as quoted in Samuels’ “Right to Difference.” “It is thus natural that she acquired, from their habits that remain the same even in a world that is constantly in flux, those bitter impressions of exile that never die among that people.” Latour, along with other scriveners, invoked her Judaic features as credentials for her to serve as tragic heroine. “[H]er face does not lack dignity,” he ventured, explaining that Félix’s body “bears the character of the Jewish race from which she comes.”

Again, a chasm separated these wild assertions from reality. Brownstein refuted biographers who claimed Félix’s parents were immigrants and referred to the two exclusively by their Hebrew names. Félix’s parents were in fact French citizens, with her father a native of Alsace-Lorraine, which hosted the largest concentration of French Jews for at least two centuries. Félix’s parents, Brownstein concluded, “must be imagined not as bearded and bewigged and Orthodox, but as an enterprising modern young couple attuned to their times.”

Félix aroused a philo-Semitism amenable to interpretations both favorable and less so. The modern reader understandably recoils at descriptions that seem to veer into race theory. Of course, we must remain cautious not to fall into the traps of presentism and anachronism. Race theory, in the odious form recognizable today, would emerge only later in the century. The sort of interest in heredity that Latour evinced could be positive, negative or neutral — and in whatever case floated freely through the idiom of his day.

Nonetheless, Félix’s life and career raise a question whose answer depends on the respondent: Did her success show that France was a relative haven of coexistence before the hour or rather that the nation’s aristocrats and audiences reveled in her craft because she was a curiosity, forever apart from the national community, not an equal member within it?

Hannah Arendt might have assumed the latter stance. In “The Origins of Totalitarianism,” she distinguished between two sorts of Jews: the pariah and parvenu. The pariah accentuated his difference and titillated staid and fusty aristocrats with his eccentricities. His invitation to the salon was predicated on the debased political and social state of his race, which made him such a coveted guest. The parvenu strived for acceptance within the existing political framework, willing to exchange membership in the national community for an outward conformity. Jews, from the 18th century until World War II, Arendt wrote, “always had to pay with political misery for social glory and with social insult for political success.” She asserted that once the political situation of French and German Jews had been improved, the salon summons stopped coming. Félix might then have been little more than the pariah’s pariah, a plum distinction in Arendt’s estimation, but something entirely different from equal citizen.

Arendt’s experience as a refugee from the Nazis no doubt informed her rueful and funereal account of Jewish history in Europe. Samuels, who will touch on these issues in an upcoming paper on evolving interpretations of Jewish assimilation in French Historical Studies, acknowledged in “The Right to Difference” the racialized valence of reactions from Félix’s fans. But he maintained this was not incompatible with political and social acceptance for her and other Jews: “Inherent in their praise for Rachel’s theatrical genius lay a new conceptualization of French culture itself — who could interpret it and who could produce it,” he wrote. “Praising Rachel’s miraculous talent became for defenders a way to oppose a narrow, deterministic conceptualization of Frenchness based on ancestral affiliation. To say that Rachel had the face of tragedy, that she was endowed with the ability to speak the lines of Racine because of her Jewish heritage and not in spite of it, was equivalent to saying that Jews, even very Jewish Jews, had as much right to French culture as Catholics.”

Félix’s conquest of the citadel of French culture earned her the lasting enmity of anti-Semites. Samuels recalled in his book that some theater reviews faulted her for having sullied French culture with her Jewishness. Janin, the aforementioned critic, bemoaned that Félix had treated Racine’s play “like a synagogue canticle.” He went on: “What would Racine have said, that great Catholic poet, if he could have known what they would one day make of his work which was destined for the Christian girls of Saint-Cyr? Surely Racine would have exclaimed: God of the Jews, you have won!”

Charles Maurice was far more virulent in his hatred of Félix, alleging that “Esther” had come off as a success thanks to Jews who had rushed the box office. “The whole of the Théâtre-Français was filled up with Israelites, from the pit to the rafters… All you could hear was German, Swiss and all the idioms of those countries where that dispersed nation had found more constant asylum.” He also blasted Félix for the features that others had celebrated, ripping the “harshness of her face” and “her angular body.”

There was tremendous irony, as Samuels noted, in lambasting Félix as not Christian enough to fill a Jewish role. Nonetheless, while modern anti-Semitism attained full flower toward the turn of the century, its outlines were visible in these responses to Félix’s performance — fears of Jewish conspiracy, race science speculation about Jewish physique, the Jew as cultural pollutant. Félix’s stardom so incensed the haters because it reflected on the place of Jews within France. And, though a small minority, their status inscribed itself in debates of larger cultural and political significance.

Félix lived in a time of transition, when the French Revolution was as much an ongoing political crusade as an historical event. Never again in its aftermath would French rulers claim the divine right of kings. The principle of equality before the law had been firmly established. The emblems associated with contemporary France, such as the tricolor flag and the Marseillaise anthem, had also originated in this period, achieving an enduring popularity that would frustrate rightists ever more.

But the republican government that the Revolution had championed would be realized only in the 1870s with the founding of the Third Republic. Georges Clemenceau, France’s World War I prime minister, could declare as late as 1891 that “the French Revolution is a bloc.” “This admirable revolution is not finished,” he thundered in the National Assembly, as rightists booed, “it continues still, we are still the agents of it, we are the same men who face the same enemies.” The will to overthrow republican government indeed persisted through to the end of World War II, when the conflict’s horrors and the Vichy regime’s collaboration with the Nazis finally discredited extreme reaction.

Thus, before the advent of the Third Republic, France stumbled along from one short-lived regime to the next: Napoleon’s First Empire, the Bourbon Restoration, Louis Philippe’s July Monarchy, the Second Republic and Louis Napoleon’s Second Empire. France’s ultimate fate — whether it would fully adopt the Revolution’s republican and universal commitments or settle for a more conservative arrangement that preserved certain elements of the ancien régime’s alliance of throne and altar, with a dash of exclusionary nationalism thrown in for good measure — was an open question.

Despite notable exceptions, most Jews cast their lot with the Revolution, which after all had emancipated them and held out a vision of France in which membership in the national community would not be predicated on Gallic ethnic origin or Catholic religious affiliation. On the 100th anniversary of the Revolution, in 1889, the chief rabbi of Paris hailed the uprising as “a new social Passover.” The community newspaper Archives Israelites effused, “This centenary can leave indifferent none of the children of Jacob, who, from all corners of the earth, salute France as the initiator of their deliverance and love it as an adopted homeland.”

When the revolts of 1848 broke out, toppling Louis Philippe’s regime and midwifing a stillborn Second Republic, Félix lent her celebrity to the cause. At the Comédie-Française, after the night’s performance had ended, Félix burst onto the stage brandishing the tricolor flag and launching into a hearty rendition of the Marseillaise. “She was a Muse… a Fury. She was superb and terrible. We shivered and trembled, and the heroic fever took hold every soul,” wrote Janin, as quoted in Samuels’ narrative. “How beautiful and valiant she was then in her inflexible mission, and how dangerous!” Flag in hand, revolutionary anthem in mouth, Félix evoked the image of Marianne, the French icon of freedom known to Americans through Eugene Delacroix’s painting, “Liberty Leading the People.”

Félix’s career was cut short in 1858, when she succumbed to tuberculosis at the age of 36. She was buried in the capital’s Père Lachaise cemetery, in a heavily attended ceremony that was officiated by Paris’ chief rabbi at the time, Lazare Isidor. Rabbi Isidor, quoted by Samuels, repudiated whispers that Félix had abandoned Judaism: “To be sure, she had too much intelligence not to die in the faith of her fathers.”

Michel Houllebecq once commented that “there is a strong love affair between France and its Jews, and we are in a moment of disappointed love.” The nuance in the novelist’s statement is absent from much of the coverage this issue receives in the press, where France is caricatured as somehow uniquely and eternally hostile to Jews. There is some truth to the truism: the nation has in past decades seen a marked rise in anti-Semitic violence, most of which has arisen from the tempestuous relationship between the country’s Jewish and Muslim citizens. (France has Europe’s largest Jewish and Muslim communities, numbering around 450,000 and five million, respectively.)

There are the cold-blooded acts of murder – the hacking to death of Ilan Halimi or the massacre at Toulouse’s Jewish day school. And then the more pedestrian experiences of vandalism and harassment – the recent defacement of tributes to former Health Minister Simone Veil, the anti-Semitic heckling of public intellectual Alain Finkielkraut. These acts of hatred large and small have rendered the open and proud expression of Jewish identity that Félix embraced rarer and rarer. Much of France’s Jewish life today occurs behind bars and bollards — and not out of some overabundance of paranoia. This is a national disgrace.

But other images and traditions oppose themselves to the kosher market riddled with bullet holes and the notion of a closed and exclusionary nationalism. When in the 1930s the United States imposed strict quotas on Jewish admission to universities, the same policy was unthinkable in France, where a strict norm of religious and ethnic neutrality, or laicité, prevailed. And the same country which cashiered Alfred Dreyfus was perhaps the only European polity in which he could have risen to the military’s General Staff.

This underscores the central paradox of French anti-Semitism: it derives its force and vitality from the hospitality that France has extended to Jews since the Revolution. This is discernible in the current discussion over a recrudescence in anti-Semitic sentiments and hate crimes, which spiked in 2018 by a whopping 74 percent. Michel Wieviorka posited in his inquiry into French anti-Semitism that Jews are resented as favorites of the Republic, which has often fumbled in integrating Muslim citizens. French Jews, some Muslims contend, are permitted a place in the national community without divesting themselves of their particularisms. Muslims, on the other hand, are not permitted such a derogation. “The Jews here have their curls, their beards, and their schools, and they wear visible signs of their faith,” confided one Muslim prisoner to the French sociologist. “But no one reproaches them of this because they’re organized and we Muslims lack that.” This Jacob and Esau redux cannot entirely account for French anti-Semitism, which like all complex social phenomena has multiple causes that can be hard to divine. France’s native anti-Semitic tradition, the post-colonial gripes of erstwhile subalterns, developments in Israel-Palestine, and the ascent of Islamism as a global force all enter into the mélange. Nonetheless, republican benevolence toward the Jews can have the effect of inflaming malice against them.

There is no evidence, for whatever it is worth, that France suffers from more anti-Semitic hate crimes than other Western European countries. According to the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, which compiles data on hate crimes throughout the Continent, France experienced 311 anti-Semitic incidents in 2017, as opposed to 672 like crimes in the United Kingdom and 233 such acts in Germany for the same year. Both countries contain Jewish communities less than half the size of France’s. Do the math and the numbers would indicate that France is the least anti-Semitic of the three. These statistics are, of course, far from dispositive assessments of anti-Semitism. Still, the tallies should give pause to those blithely depicting France as some anti-Semitic hellscape.

The paradox of French anti-Semitism can also be observed in regard to high-profile incidents of hateful rhetoric. Leon Blum, who served as France’s prime minister in the 1930s, was nicknamed by his detractors “Karfunkelstein,” an epithet meant to highlight his alleged foreignness. Charles Maurras, the far-right intellectual and founder of the Action Française, wrote that Blum was “a naturalized German Jew” who deserved to be “shot in the back.” Veil, a survivor of Auschwitz and stalwart of the European Union, wore long sleeves her entire life to hide her concentration camp tattoo. She was vilified on the French right as a Nazi when she pushed abortion legalization in the 1970s.

These spasms of anti-Semitism were possible only because French society has welcomed Jews. France has had three Jewish prime ministers — in addition to Blum, René Mayer and Pierre Mendes-France. And the country hosts a veritable procession of Jewish intellectuals, running from Éric Zemmour on the far-right to Éric Hazan on the far-left. Such is the continuity of French anti-Semitism from the time of Rachel Félix to now: it reflects at lower intensity the light of an inclusive tradition that has shone bright on France’s Jews.

More than a century and a half after her death, Félix has not disappeared from Paris. Her grave can be found among the city’s great and good at Père Lachaise. Her portrait graces the Comédie-Française and the capital’s Jewish museum. (The lengthy biographical sketch of Felix on the theater’s website curiously omits mention of her Jewish roots.)

The 18th arrondissement features the Avenue Rachel, which, brief like its honoree’s stage name, runs all of one block. I strolled over there one morning in early February, and there was not much to see, some residential buildings and a couple of dusty-looking bistrots. Félix also has to share the neighborhood with stars of more recent vintage — Dalida’s grave is a stone’s throw away, as is the atelier of the painter Toulouse-Lautrec, But the tribute has survived even as successive architects and politicians have remade the face of the city.

Samuels acknowledged in an interview with me that Félix had largely fallen into obscurity, but insisted on her continued relevance. “She lived in a time that was much less mediatized, but in some ways she laid the path for those who would come after her, including Sarah Bernhardt,” he said, name-checking the renowned French Jewish actress of the belle epoque. “Her career is a reminder that France has been far superior in welcoming Jews than many other countries, including in certain periods the United States.”

Félix proves, Samuels averred, that French universalism does not require the renunciation of particular religious or ethnic identities. “Rachel was embraced not in spite of her Jewishness, but because of it,” he said. He posited that Félix’s example could prove instructive not only to France’s Jews, but also to the country’s Muslims, who have faced accusations of failing to adequately assimilate. “French universalism,” he said “has always been a site of contestation, a struggle for minority groups to assert themselves.”

Félix’s legacy could soon resurface in a huge if inadvertent manner. Some are now clamoring for the recently deceased Simone Veil to become the new model for the republican mascot Marianne. The idol is a ubiquitous emblem of France, where her silhouette is printed on all official state documents and her bust can be found in many town halls. Marianne, whose features were initially borrowed from a composite of unnamed individuals, has more recently taken on the likeness of famous French women, among them the singer Mireille Mathieu and actress Catherine Deneuve. Four regime changes and more than a century separate Félix and Veil, but their example demonstrates that French Jews are not a nation within a nation, but rather an integral part of the nation, and can even embody it.

Daniel J. Solomon is a freelance writer based in France. Follow him on Twitter @DanielJSolomon

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning journalism this Passover.

In this age of misinformation, our work is needed like never before. We report on the news that matters most to American Jews, driven by truth, not ideology.

At a time when newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall. That means for the first time in our 126-year history, Forward journalism is free to everyone, everywhere. With an ongoing war, rising antisemitism, and a flood of disinformation that may affect the upcoming election, we believe that free and open access to Jewish journalism is imperative.

Readers like you make it all possible. Right now, we’re in the middle of our Passover Pledge Drive and we need 500 people to step up and make a gift to sustain our trustworthy, independent journalism.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Join our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Our Goal: 500 gifts during our Passover Pledge Drive!