Susan Klebold Doesn’t Believe God Is Watching Over Her Family Anymore

A Seemingly Typical Teenager: A photo of Dylan Klebold from the book “A Mother’s Reckoning,” by Susan Klebold. Image by Courtesy of the Klebold Family

Image by Courtesy of the Klebold Family

In the days after Dylan Klebold along with Eric Harris shot and killed 12 students and one teacher and then himself at Columbine High School on April 20, 1999, his mother, Sue Klebold, remembered a kind of “religious warfare” in the community of Littleton, Colorado. The notion that she hadn’t raised her son to be a moral human became a prevalent theory that followed her for years.

“There was an assumption from the tragedy that Dylan had not been taught right from wrong,” she told me recently in a phone interview.

In her newly released book, “A Mother’s Reckoning: Living in the Aftermath of Tragedy,” she writes about trying to instill a moral code in her son. During his junior year in high school, 12 months before the shootings, he and Harris broke into a van.

After his mother retrieved him and drove him home, she stopped him as he ran upstairs, and then sat him down on the steps. She felt frustrated and surprised by what he had done, and told him that he needed to live by the 10 Commandments.

Sue Klebold thought her message had gotten through. “Dylan was a malleable person, and whenever we talked about something he would come around to my point of view, and so in my mind it was an effective conversation,” she said.

These ideas of morality and religion simmer underneath Klebold’s recounting of her son’s life in the years before the shootings. She tried to instill them in him as far back, in some instances, as his early childhood, but they never really got through to him. In Klebold’s attempt to come to terms with her son’s actions, she portrays him as a suicidal depressive instead of the “monster” depicted in the media.

“She attempted to paint a very real portrait of Dylan and insisted on his humanity,” said Andrew Solomon, who wrote about the Klebolds in his 2012 book, “Far From the Tree: Parents, Children and the Search for Identity,” and wrote the introduction to Klebold’s memoir.

She discusses her own humanity as well by outlining her blindness to her son’s depression and unhappiness, and to his plan to kill. At one point in the book, when, during his high school years, he forgets Mother’s Day, Klebold snaps with frustration and shoves him against the fridge. He tells her he feels angry and doesn’t know if he can control that anger, and she brushes off his reaction as normal adolescent behavior. “He was a teenage boy and a lot of things got him angry, but he was angry in a very appropriate teenage boy sort of way,” she said. “He would get irritated when we corrected his driving, and do that teenage eye roll thing. It was all very normal.” Looking back, Klebold realizes Dylan’s behavior might have suggested a larger problem.

“I was not aware that a change in behavior might be indicative of a mental health issue getting started,” she said.

Childhood's End: Three days before the shootings, Dylan Klebold attended his high school prom. Image by Courtesy of the Klebold Family

In a six-week investigation by Time magazine after the shooting, reporters Nancy Gibbs and Timothy Roche obtained what were later called “The Basement Tapes.” They were shot in Harris’s basement and showed footage of the two boys on several occasions, cradling weapons and spewing racial slurs against Jews, Latinos, African Americans and others. Klebold said she didn’t find it odd that her son wore a floor-length leather jacket, as she herself had tried to be different by wearing cowboy boots and moccasins when she attended private school from first to 12th grade.

“The mythology was that they were Nazis and Goths, and it was wrong, and people still believe this is fact, even though there is no evidence to show this was true,” she said.

Susan Klebold grew up in Ohio with a Jewish father and a Christian mother. She attended a Reform Jewish synagogue and went to church with her grandmother. Her private school had a chapel, which she visited every day. When she was a child, this mixed religious household confused her, and she grappled with her relationship to God and to heaven and hell. She approached a rabbi who “didn’t teach black and white thinking” to discuss the afterlife, and he told her he believed in another chapter after death.

As she grew older, her ties to Judaism disintegrated. She hasn’t practiced since she left her childhood home. As a mother, she sometimes recited the Ten Commandments as a moral code, and at other times, she recited, “Now I lay me down to sleep” before bedtime, along with other prayers. Depending on the calendar, the family fused Passover and Easter into one dinner.

“I was very unstructured about it,” she said of religion. After the Columbine tragedy, she had a fleeting thought that if her son had had a formal religious upbringing, he might not have killed a dozen people and himself.

Religion doesn’t play a prominent role in the book, but when I spoke with Klebold, she touched on Columbine High School’s ignorance of Judaism, describing Columbine as upper middle class, Caucasian and Christian. She also used the words “toxic” and “judgmental.” She said she doesn’t know a single Jewish person in town, and one December, when she tried to buy Hanukkah candles at the grocery store, the clerks looked at her blankly.

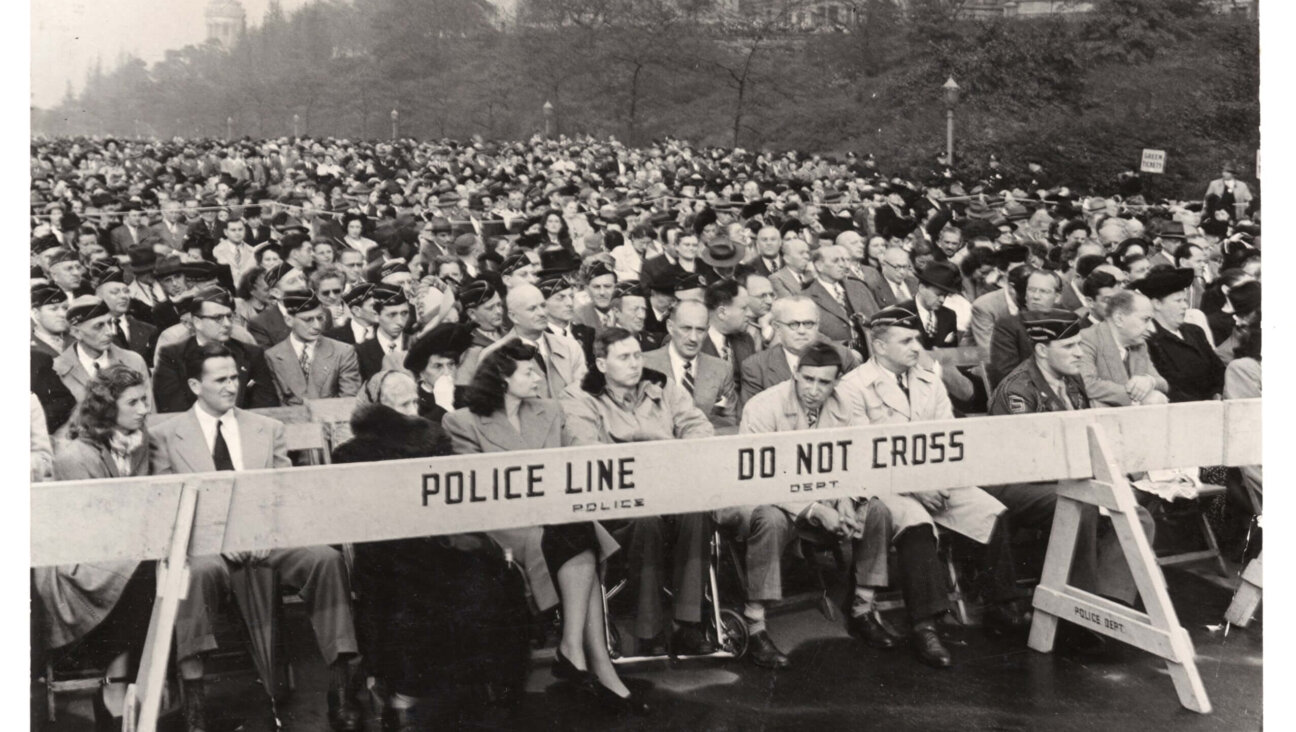

To illustrate the religious environment of the area, she mentioned that Franklin Graham, a well-known evangelist, performed the memorial service for the slain children in front of a crowd of 65,000 that included Al Gore, the vice president at that time, who spoke. The video of the memorial reveals a service heavy on Christianity, with church officials and references to Jesus Christ. She isn’t aware of any synagogue in Littleton, and a Google search doesn’t turn up results. Klebold said her son didn’t identify with being Jewish. At one point in the book, he objects, out of embarrassment, to reciting the four questions at a Seder. According to Klebold, he reveals this frustration on “The Basement Tapes.” Then, she said, Eric Harris stops and says, “I didn’t know you were Jewish,” after which Dylan Klebold seems to turn fearful that Harris might target him.

“It was a very odd moment,” she said.

Image by Courtesy of the Klebold Family

After the shootings, Klebold sought solace from the now retired rabbi Steven Foster at Temple Emanuel, in Denver. Her attorney attended his synagogue. She told me she remembered Foster suffering a backlash after saying Kaddish for her son, but Foster doesn’t remember that.

“Ultimately, [his parents] were also victims,” he said. “They didn’t do this, their son did. He was misguided and all of that. I’d do the same thing tomorrow, even if people get angry. I don’t care.”

The community’s belief that Dylan Klebold’s upbringing played a role in his actions frightened his mother. “The governor of Colorado cited parenting as a causal factor in his first public appearance after the shootings. But Tom [her now ex-husband] and I knew exactly what had happened in our home all those years we parented Dylan, and we were equally sure the answer wasn’t there,” she wrote in the book. She continued, “Morality, empathy, ethics — these weren’t one-time lessons, but embedded in everything we did with our kids.”

“I think school shootings bring up good and evil, and people turn to religion because it’s the ultimate disruption of a moral code,” said Solomon.

At the end of our conversation, Klebold acknowledged one’s upbringing as irrelevant to these tragedies and denounced the idea that religion played any role.

“Anyone from any background can have mental issues,” she said.

Klebold says that she used to believe God was watching over her family. But after the shooting, she changed her mind. “[It] made me realize that none of us have any control over anything, really,” she said.

Britta Lokting is the Forward’s culture fellow. Twitter @brittalokting

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning journalism this Passover.

In this age of misinformation, our work is needed like never before. We report on the news that matters most to American Jews, driven by truth, not ideology.

At a time when newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall. That means for the first time in our 126-year history, Forward journalism is free to everyone, everywhere. With an ongoing war, rising antisemitism, and a flood of disinformation that may affect the upcoming election, we believe that free and open access to Jewish journalism is imperative.

Readers like you make it all possible. Right now, we’re in the middle of our Passover Pledge Drive and we need 500 people to step up and make a gift to sustain our trustworthy, independent journalism.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Join our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Our Goal: 500 gifts during our Passover Pledge Drive!