Allen Ginsberg, Siegfried Sassoon in collection of letters about LGBTQ love and friendship

‘The Love That Dares’ looks at poems and letters exploring queer relationships from Sappho to the 21st century

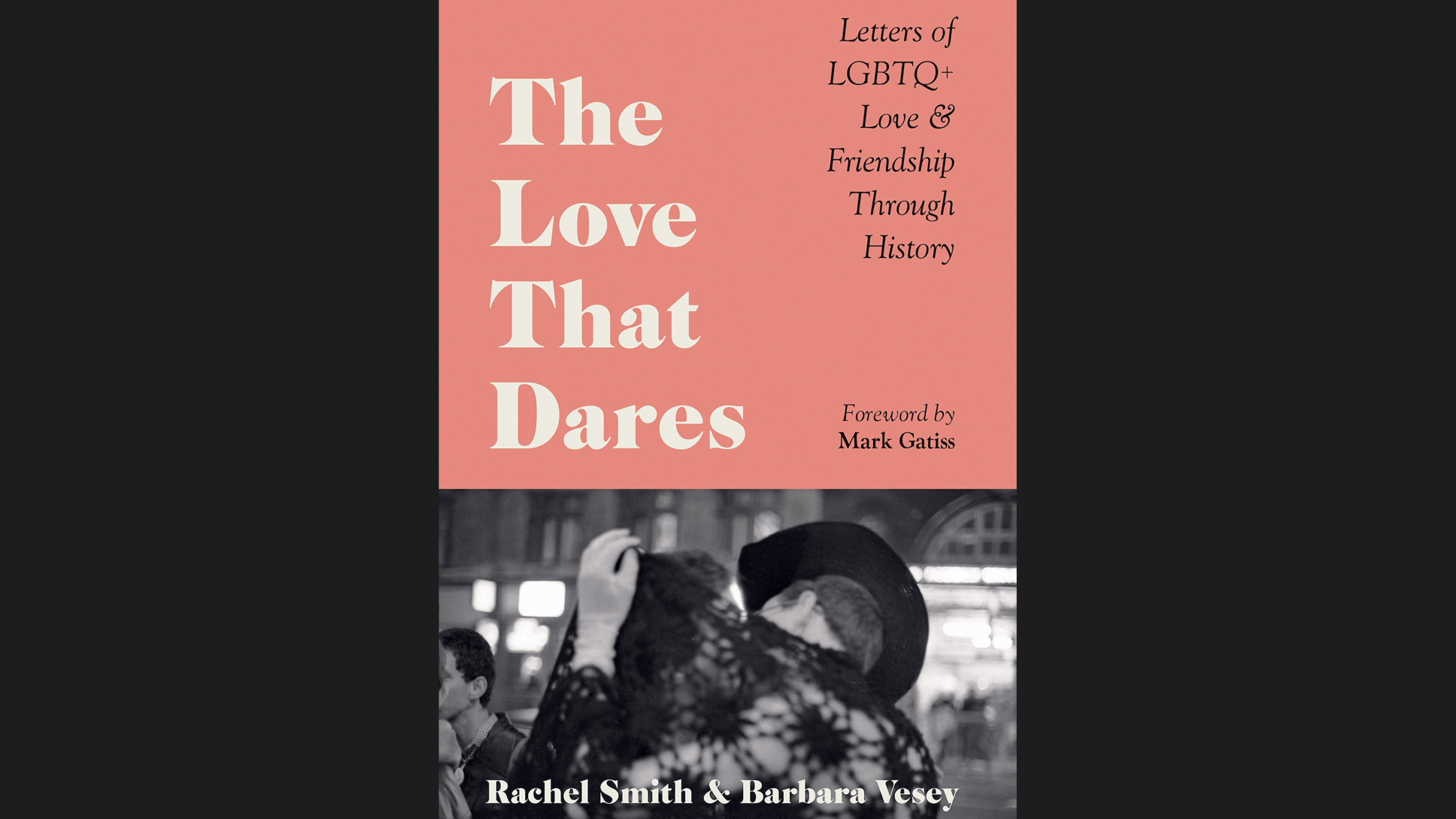

“The Love That Dares” is a new collection of letters and poems expressing LGBTQ love and friendship. Courtesy of Ilex Press

A new book called “The Love That Dares” offers a collection of letters and poems exploring LGBTQ love and friendship. Some of those whose words are quoted are famous, some are not so famous. Some had secret relationships while others refused to hide. Among the three dozen individuals included are three with Jewish heritage: the poets Allen Ginsberg and Siegfried Sassoon and the artist Gluck (aka Hannah Gluckstein).

The collection starts with poetry by Sappho and hopscotches across the centuries to include letters from King James I, Emily Dickinson, Susan B. Anthony, John Cage, Lorraine Hansberry and Audre Lorde.

The book’s title refers to a line from a poem, “Two Loves,” written by Oscar Wilde’s lover, Lord Alfred Douglas: “I am the love that dare not speak its name.” The book was published in the U.S. to coincide with Pride Month.

The book’s co-editor, Barbara Vesey, is an old friend of mine and an archivist at the Bishopsgate Institute, a London library and cultural hub established in 1895. I visited London recently and Vesey gave me an informal tour of Bishopsgate, including its extensive collection of LGBTQ-related artifacts, diaries, letters and posters — everything from T-shirts and leather to protest signs, zines, artwork and photos. When I got home from my trip, a copy of the book was waiting for me. I interviewed Vesey and her co-editor Rachel Smith about it via email.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

How is your work at Bishopsgate connected to this book?

Rachel Smith: The collection process for the book was greatly informed by our collecting policy at work. Bishopsgate Institute’s collections are done very much from the ground up, by providing a safe haven for archives made by people who are forced to live within society’s margins and are thereby left in the margins of other institutions’ collections. So this ethos carried over into selecting letters for the book. We wanted to feature stories both that people would be familiar with and ones they wouldn’t; ones that are already a footnote in human history and ones that still need to see the light of day.

Books of letters can be hard to read straight through, but this collection is so engaging, partly thanks to the short bios you provide for each person. How did you choose who would be included and how did you put it together?

Barbara Vesey: We drew up a wish list of whom we’d like to be included, which then necessarily got whittled down as we researched whether they even had letters that were available, then if we could get our hot little hands on them and be granted permission to publish them. We knew from the beginning that we didn’t want to include a lot of ‘‘tragic’’ letters – early on when we were casting about for ideas, a few people came up with instances of really abusive or one-sided relationships. We were keen from the off for the book to be life-affirming. Also we decided early on that we didn’t want the letters to be only between lovers, but to include letters of friendship and letters from one queer person to another whom they saw as having opened a door or created a path for them towards loving and accepting themselves.

Let’s talk about the individuals in the book with Jewish heritage, starting with the British poet Siegfried Sassoon, whose father was Jewish (his mother was not). Not a household name in the U.S. but what should we know about him? And tell us about his letter to the author of the book “The Intermediate Sex.” Sassoon says that until reading the book, “I couldn’t allow myself to be what I wished to be.”

Barbara Vesey: Siegfried Sassoon (1886-1967) was born into a cultured and artistic family of Iraqi Jews. He was one of a group of poets who wrote anti-war poems that emerged directly from their experiences during World War I. The letter we’ve included was written in 1911, when Sassoon was 25, to the maverick Socialist, vegetarian, activist and maker of his own shoes, Edward Carpenter (1844-1929), who lived openly with his lover for over 20 years in a village in the north of England. I love the gushing nature of this letter – it seems clear that the young Sassoon had a bit of a crush on Carpenter and is seeking to flatter and impress him. The fact that Sassoon mentions a couple of photographs of himself that he has enclosed in the letter is particularly endearing. Also this letter speaks to that theme I mentioned earlier, of someone looking up to and thanking an older gay person for making them feel validated, worthy of love and respect. Sassoon writes as a direct result of having read Carpenter’s book, “The Intermediate Sex,” thanking Carpenter and saying, ‘‘I am a different being, and have a definite aim in life and something to lean on … I write to you as the leader and the prophet.’’

What should we know about the British painter Gluck (1895-1978, aka Hannah Gluckstein)? The letters you include reflect Gluck’s passion for their lover, Nesta Obermer, with unbridled sentiments like, “My own darling wife … I love you with all my being.”

Rachel Smith: Gluck didn’t just live outside of the gender binary. Gluck straight up rejected it, along with a first and last name, no prefixes or suffixes either. Just Gluck. It’s tempting to describe Gluck as nonbinary or gender-fluid or genderqueer, but Gluck didn’t have the language we have today, and so in an attempt to be truthful without being anachronistic, we describe Gluck as “gender nonconforming.”

And finally Allen Ginsberg, the late great Beat poet. One of his most famous works, “Kaddish,” takes its name from the Jewish mourning prayer. Your book includes two notes he wrote to his partner of 43 years Peter Orlovsky, describing Orlovsky’s “sweet sex talk” as “fresh as a summer breeze.” Tell us more.

Barbara Vesey: I had to jump through a good many hoops and went down so many dead ends trying to find out who had the copyright for Ginsberg’s (and Orlovsky’s) letters – and that’s why (full disclosure) there are only two short notes Ginsberg wrote to Orlovsky in 1958. I tried to make up for this by making the mini-bio a bit less mini. Ginsberg (1926-1997) and Orlovsky (1933-2010) met in San Francisco in 1954 and lived together in an open relationship (Orlovsky had relationships with both men and women throughout his life) for 43 years, until Ginsberg’s death. I’m glad I persisted through all the hurdles, as I feel that the letters we’ve been able to include show a sweet and vulnerable side to Ginsberg that are not always associated with the excoriating anger of his poem ‘‘Howl’’ or even, as you mention, the grief of ‘‘Kaddish.’’

This article has been updated to note that Siegfried Sassoon’s mother was not Jewish.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO