7 surprising facts about Jewish weddings, courtesy of a new exhibit

The inaugural exhibit at the Jewish Theological Seminary’s new library challenges assumptions about the way Jewish weddings have “always” been done

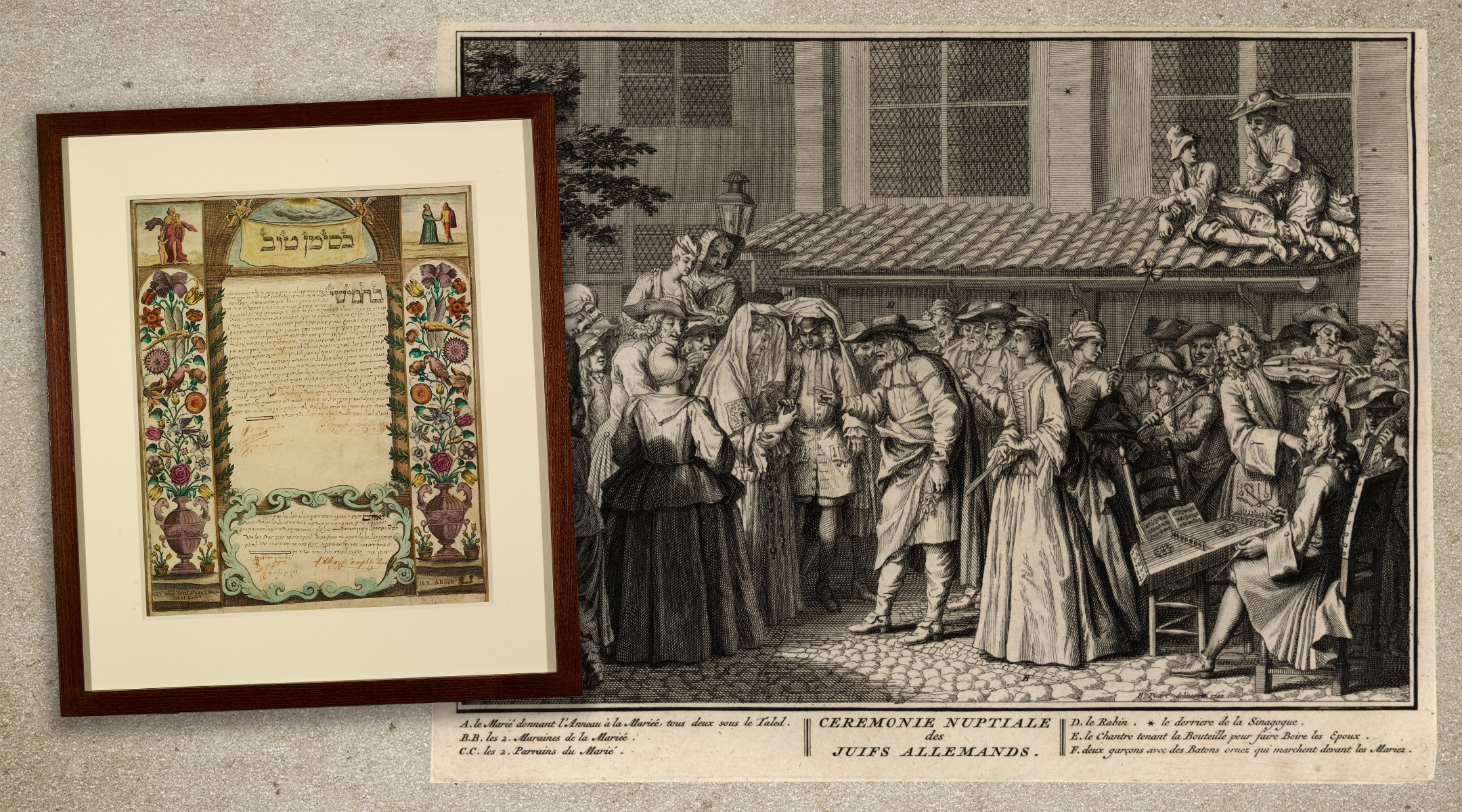

A trove of artifacts illuminate the history of Jewish weddings, including a ketubah (Jewish marriage contract) dating to 1729 from the Hague and pages from Bernard Picart’s 1741 tome, “Religious Ceremonies and Customs of All the Peoples of the World.” (Courtesy JTS Library)

(New York Jewish Week) — If you’ve ever been to a Jewish wedding, or 20, there are some things that you come to expect: the officiant and the couple standing under a wedding canopy, or huppah; the dramatic breaking of a glass at the conclusion of the ceremony; a lively hora dance in which the newly married couple are lifted in their chairs.

But the inaugural exhibit at the newly opened library at the Jewish Theological Seminary, the Conservative Jewish educational institution in Morningside Heights, challenges many assumptions about the way Jewish weddings have “always” been done.

Using visual materials such as the ketubah (Jewish marriage contract) and rare Judaica, the exhibit “To Build a New Home: Celebrating the Jewish Wedding” introduces visitors to the innovations and traditions of Jewish marriages from Talmudic times to the present.

JTS’s new library, a prominent feature of the campus’s five-year renovation and construction project, was officially unveiled in May when JTS formally welcomed its new chancellor, Shuly Rubin Schwartz. Funded in large part by the institution’s $130 million sale of air rights and adjoining property, the new campus boasts upgraded residences, a 200-seat auditorium and large open spaces for the arts, ceremonies and services.

The updated library now has a public exhibition gallery equipped with climate-controlled areas to protect one of the largest collections of rare Judaic artifacts and manuscripts in the world.

“‘To Build a New Home’ both allows us to show some of our most stunning materials and celebrate the library, the new home of our collection,” said David Kraemer, director of the library at JTS.

The exhibit, which aims to show how Jewish weddings have developed in their cultural contexts, yields some surprises, such as the absence of a huppah in a 1749 etching of German Jewish wedding customs, or the presence of nude women in the design of a 1729 ketubah from the Hague. Seen as a whole, “To Build a New Home” reveals that the Jewish wedding as we think we know it is the result of centuries of cultural integration and evolution.

Inspired by the exhibit, which is on view through Aug. 14, the New York Jewish Week chatted with JTS library curators and other players in the field of contemporary Jewish marriage about long-held assumptions about Jewish weddings, both past and present. Here are seven facts that might surprise you.

1. The huppah wasn’t always a part of Jewish wedding ceremonies.

Considered a defining symbol of contemporary Jewish weddings, the wedding canopy was used in Jewish weddings beginning in the 15th century, and didn’t become popular in Ashkenazi settings until the 16th century. “The huppah originated from Christian practice, from the ceremony of installing bishops into their posts,” Kraemer said. “This practice of Christian clergy was later adapted for Jewish use.”

A Roman ketubah from 1836. (Courtesy JTS Library)

2. The ketubah and other Jewish marriage documents historically empowered women to set specific conditions.

Jewish wedding contracts nowadays typically contain generic, formulaic language, such as the traditional general promise for the groom to “honor, feed and support” the wife, or egalitarian versions that say both partners accept all the conditions of betrothal and marriage.

But that was not always the case. “Historically, if a woman wanted to insist upon a certain condition, she would do it and those conditions were put into the ketubah,” Kraemer said. Brides could introduce legally binding demands, such as whether the future family would follow Sephardic or Ashkenazi customs in the home, or if the husband could take a second wife. (Sadly, there are no known examples of couples pre-arranging whose job it is to clean the litter box.)

In the exhibit, visitors can see a fragment of a prenuptial agreement from the Cairo Genizah (a collection of Jewish manuscript fragments that date to the Middle Ages) in which the groom agrees that his mother-in-law will reside with the couple, promising that he will not abuse her physically or emotionally.

3. Intermarriage has been a feature of Jewish life since the very beginning.

It’s true: In the bible, Moses married Zipporah, a Midianite. The Book of Ruth, which is traditionally read on Shavuot, describes the marriage of Boaz to Ruth the Moabite; Ruth becomes what’s considered the first Jew by choice and her descendants include King David.

According to Keren McGinity, interfaith specialist for United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism, the congregational arm of the Conservative movement, even if there was historically a lack of sanction in organized religion for marriages between Jews and non-Jews, that doesn’t mean they didn’t occur. In fact, the first Jewish-Christian intermarriage on American soil, said McGinity, was in 1656, when Solomon Pietersen married a Christian woman in New Amsterdam (later renamed New York).

4. Shtick is older than you think.

Shtick, or the tradition of making the newly married couple laugh on their wedding day with an impromptu cabaret of skits, posters, acrobatics, limericks and more, is just that: a capital-T Tradition that dates back to at least the 13th century. In the exhibit, visitors can enjoy an example of some old-school wedding shtick with a bawdy poem recorded in the Mahzor Vitry, an 13-century text that contains Asheknazi laws, prayers and liturgical poems.

The poem begins in Hebrew with a biblical allusion “to the fragrant mound” (Song of Songs 5:13), but ends with a naughtier twist in French: “the groom has arrived.” You can probably figure out what kind of “mound” we’re talking about here.

A 1749 ketubah from Venice. (Courtesy JTS Library)

5. Jewish weddings, like all aspects of Jewish life, do not exist in a vacuum.

From the huppah itself to the intricate decorations on a ketubah, Jewish wedding traditions have been deeply influenced by their cultural context. “To Build a New Home” includes a ketubah that was most likely illustrated by a Christian artist, featuring iconography deeply influenced by Renaissance art, as well as a poem that alternates between French and Hebrew.

For curator Sharon Liberman Mintz, one of her favorite objects on display is an 18th-century illuminated poem from Mantua, Italy that depicts the Roman gods Mercury and Saturn. The inclusion of this imagery is a play on the Jewish couple’s names: In Jewish astrology, Kohav (the name of the bride) is synonymous with Mercury and Shabbetai (the name of the groom) is equivalent to Saturn.

6. The exhibit name, “To Build a New Home” is adapted from a central theme of Jewish weddings.

The Jewish wedding is designed to guide couples through the liminal moment in which they leave their respective separate lives and venture into a new space: the spiritual and physical home they build together.

“This idea of building a new home is very central to the theme of weddings and it is reflected in the iconography of many of our ketubbot [the plural of ketubah],” Mintz said. “You’ll see twisted columns, pediments, and archways — the imagery very much evokes this concept of home-building.” The name is also perfect for the inaugural exhibit in a renovated JTS library: a new home to share gems of Jewish heritage with the Jewish community and the public.

7. Even today, Jewish weddings continue to grow and evolve.

The breathtaking artifacts on display in the exhibit are really just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to present-day Jewish weddings. Though the strength of the JTS library’s collection lies in Jewish artifacts dating prior to World War I, Jews continue to develop Jewish wedding texts, rituals and objects to balance tradition with the diverse needs of the community. Missing from “To Build a New Home” are Jewish wedding contracts from LGBTQ unions, for example, as well as artifacts from the Reform and Reconstructionist movements and interfaith marriages. However, both Mintz and Kraemer said they are open to diversifying the collection in the future with donations of ketubahs and other artifacts.

“To Build a New Home: Celebrating the Jewish Wedding” is on view at the Jewish Theological Seminary Library at 3080 Broadway until August 14.

This article originally appeared on JTA.org.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO