How film brought Nazis to justice at Nuremberg

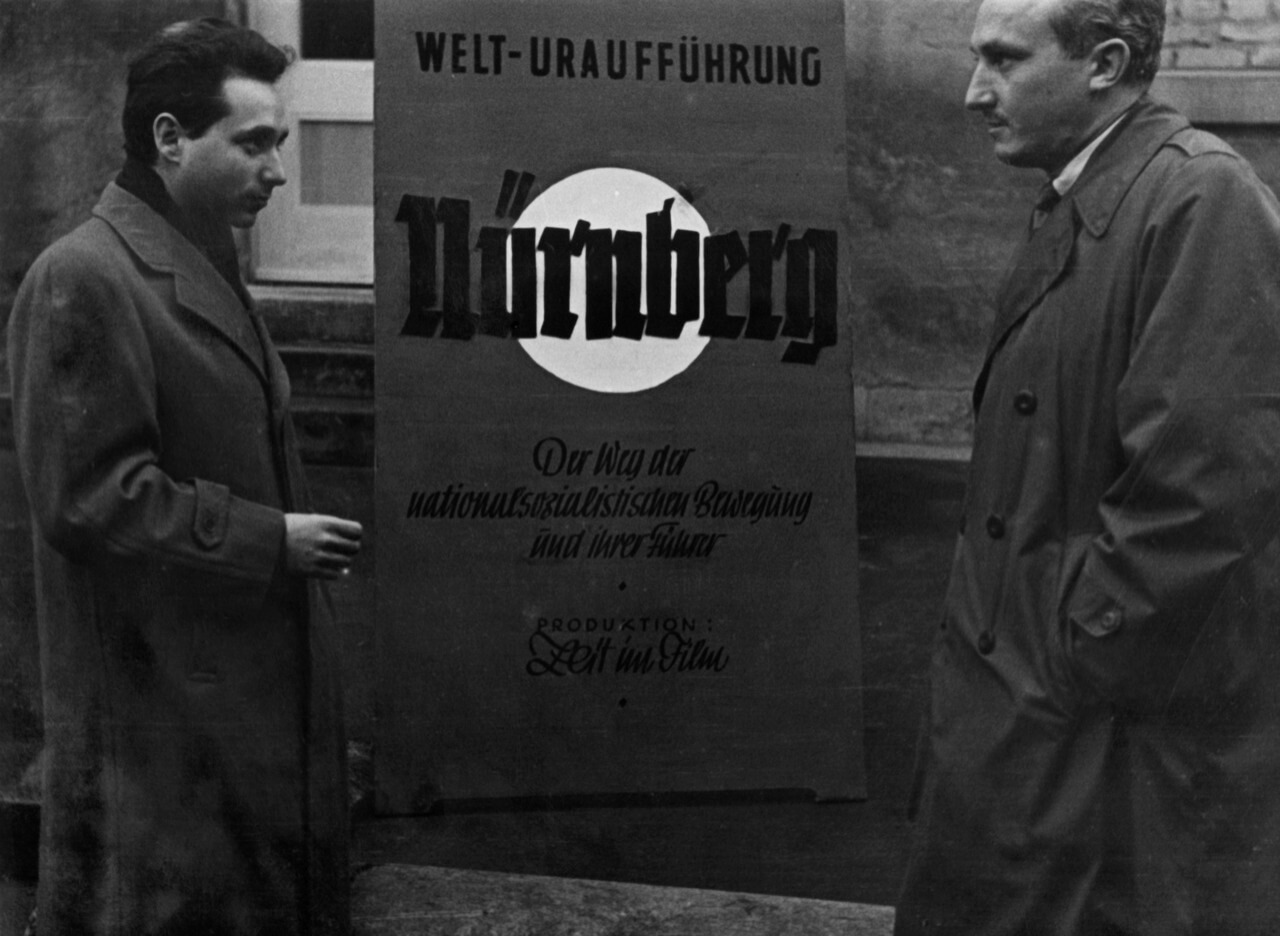

Stuart Schulberg, left, by a poster of his 1948 film Nuremberg: Its Lesson for Today, which premiered in Stuttgart, Germany, but never had a proper American release in his lifetime. Courtesy of Kino Lorber

In the summer of 1945, the war in Europe was over, the Allies shifted their focus to bringing Germany to justice and 23-year-old Stuart Schulberg was preparing for a trip that would forever shape our understanding of the Holocaust.

Stuart and his brother, novelist and screenwriter Budd Schulberg, were part of the Office of Strategic Services photographic unit, under the command of legendary director John Ford. Their task was to travel through the rubble of postwar Europe collecting filmed evidence for the Nuremberg Trial, which prosecuted Nazis for their crimes.

“Sometimes I think the job is a few sizes too big for me,” Stuart wrote in a letter to his wife, Barbara, before he shipped out from Washington, D.C., with a crew of editors. “I suppose I’ve never had so much responsibility. There’s so much to do, and so much of it is so important that I grow terrified.”

Stuart and his comrades were among the first to bear witness to scenes of the Warsaw ghetto, massacres in Eastern Europe, the stacks of skeletal bodies at Auschwitz and other chilling images that form our collective memory of the Shoah. But their unit’s mission, and the 1948 documentary Stuart made of the trial, are a little-known history. Even his daughter didn’t know much about his work for Nuremberg until years after he died.

“You don’t always ask your parents what they did before you were born,” Sandra Schulberg, Stuart’s daughter and the president of IndieCollect, a company that rescues and restores American independent films, said in a phone interview. “And this can turn out to be a missed opportunity that, in some cases, really is a historical miss.”

It was only in 2002, after the death of Sandra’s mother, Barbara, that she found boxes of material from Stuart’s time in the OSS, including a 16 mm print of his film Nuremberg: Its Lesson for Today.

The reels had been sitting in a corner for years, with some using it as a coaster for wine glasses, Sandra Schulberg says in the documentary Filmmakers for the Prosecution, which is based on her monograph of the same name.

Filmmakers for the Prosecution follows Budd and Stuart’s journey through Germany and the suppression of Stuart’s film of the trial by members of the U.S. military, eager to work with West Germany and unwilling to show Americans working alongside Soviets in the courtroom. While the American government used Nuremberg as a denazification tool in Germany, Stuart’s hope to present it to a general audience in America went unrealized until Sandra’s restoration.

Together, the documentaries tell a belated story of how film was first used to set a new standard for the prosecution of war crimes.

Filmmakers for the Prosecution director Jean-Christophe Klotz, a prolific documentarian for French television, interviewed historians who explain how U.S. Chief of Counsel Robert H. Jackson made a film screen the focal point at the Nuremberg Palace of Justice, placing the judges where the jurors usually sat. Klotz also spoke to Niklas Frank, the son of Governor-General of Occupied Poland Hans Frank, about his father’s stunned reaction to the three-hour film assembled by the OSS.

Like Sandra Schulberg, Klotz has a family connection to the material. His grandfather was deported to Auschwitz and his father survived the war in hiding and later worked as an editor for Stuart Schulberg. Klotz also knows what it’s like to try, and fail, to use film as testimony.

In 1994, Klotz was a war reporter covering the Rwandan genocide. “I was filming that because I really thought it would change the story,” Klotz recalled.

The experience of documenting atrocities, but being unable to stop them, soured the work of journalism for him, leading to his pivot to direct his own films. He believes Stuart Schulberg, while successful in convicting Nazis, may have felt similarly after spending years producing his film about Nuremberg, only to have its American release thwarted by politics. (Nuremberg was Stuart’s first film as a director; he later worked on films for the Marshall Plan and spent years as a producer for television before his death in 1979, at the age of 56.)

Featuring late-in-life remembrances of Budd Schulberg, who died in 2009, and propelled by Stuart’s letters, read by his son KC, Filmmakers for the Prosecution finds a personal way into perennial questions about international justice and film’s power, and limitations, for delivering it.

In one moment, Budd recalls how a massive cache of hidden films, abandoned by the retreating Wehrmacht, caught fire as the OSS approached. Tipped off to another trove, the company arrived to see that one in flames as well. With the destruction of those reels, likely by Germans covering their tracks, countless stories were lost forever. What the Schulbergs and their colleagues had left is largely what history remembers.

“The most interesting thing to me was that their film is called Nuremberg: Its Lesson for Today,” said Klotz. “The lesson is that everybody says Nuremberg is extraordinary. It’s a milestone for civilization and all that. They have the film and they decided not to not to show it.”

Now, after nearly 75 years, the film, and the story of how it came to be are finally available. Its lesson will always be relevant — today and tomorrow.

Filmmakers for the Prosecution opens on International Holocaust Remembrance Day, Jan. 27, 2023, at The Downtown Community Television Center in New York. Tickets and more information can be found here.

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning journalism this Passover.

In this age of misinformation, our work is needed like never before. We report on the news that matters most to American Jews, driven by truth, not ideology.

At a time when newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall. That means for the first time in our 126-year history, Forward journalism is free to everyone, everywhere. With an ongoing war, rising antisemitism, and a flood of disinformation that may affect the upcoming election, we believe that free and open access to Jewish journalism is imperative.

Readers like you make it all possible. Right now, we’re in the middle of our Passover Pledge Drive and we still need 300 people to step up and make a gift to sustain our trustworthy, independent journalism.

Make a gift of any size and become a Forward member today. You’ll support our mission to tell the American Jewish story fully and fairly.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Join our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Only 300 more gifts needed by April 30