Descendants of Holocaust perpetrators are writing about their history — what can we learn from them?

Writing about their Nazi heritage, journalists Burkhard Bilger, Linda Kinstler and Géraldine Schwarz showcase a new kind of Holocaust testimony

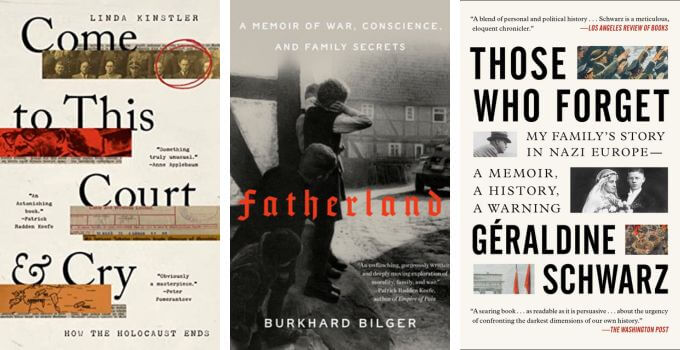

Three new books by grandchildren of Holocaust perpetrators excavate painful family histories. Photo by The Forward

Browsing a bookstore in Riga, Latvia, in 2016, journalist Linda Kinstler came across a spy novel starring her grandfather — or at least someone sharing his name, Boris Karlovics. In the novel, You Will Never Kill Him, Karlovics is a former member of the Arajs Kommando, a Latvian police squad that cooperated with the German army to kill thousands of the country’s Jews, and a current KGB agent tasked by the Soviet government with identifying his former comrades. When he botches an attempt to kidnap Herberts Cukurs, a Latvian celebrity who also served in the Arajs Kommando, his KGB superiors assassinate him.

The choice of name was no coincidence. Kinstler’s actual grandfather shared some essential features with the book’s Boris Karlovics. He was a member of the Arajs Kommando. He likely did work with Cukurs, an airman known before the war as the “Latvian Lindbergh” and after as “the butcher of Riga,” who in real life fled Latvia for Uruguay and was assassinated by Mossad agents. And after becoming a KGB agent, he vanished without a trace in 1949.

Kinstler began researching her grandfather’s past as Latvian nationalists and right-wing groups were attempting to rehabilitate Cukurs’ image and deny the counry’s indisputable participation in the Holocaust. In her new book, Come To This Court and Cry: How The Holocaust Ends, Kinstler uses the Cukurs case, and her personal connection to it, to explore contemporary debates about Holocaust memory. Kinstler warns readers in her prologue that this book won’t provide the cloak-and-dagger thrills of a spy novel. Implicitly, Come To This Court and Cry promises another kind of satisfaction: That historians can explain the past actions of relatively obscure men like her grandfather, and that those individual stories can serve as a window into a broader historical period.

Come to This Court and Cry is one of several recent family histories published by grandchildren of Holocaust perpetrators. Notable among them are Burkhard Bilger’s Fatherland, in which the author traces his grandfather’s journey from rural teacher to Nazi Party chief, and Géraldine Schwarz’s Those Who Forget, a damning chronicle of the ways her German grandfather profited from his country’s persecution of Jews. Using a combination of family interviews and archival research, these authors seek not only to grapple with dark heritages but also to address larger questions about how “ordinary people” came to participate in the Holocaust.

Yet the historical record, never particularly cooperative with those who would wrangle it into a cogent narrative, often stymies them. The authors are frequently unable to find enough information to explain their grandfathers’ actions or motivations during the Holocaust. And even when the archives yield revealing tidbits, the particularities of these men’s individual lives prevent them from serving as metaphors for their societies. Ultimately, these books are far more successful as memoirs exploring how a perpetrator’s deeds can reverberate through generations than as investigations that offer a blueprint for avoiding or prosecuting fascism today.

Bilger, Kinstler and Schwarz, all journalists, are adept at shaping evidence into textured imaginations of their grandfathers’ lives. Bilger relies on interviews and trips to his family’s Black Forest hometown to piece together his grandfather Karl Gönner’s impoverished upbringing, his harrowing experience fighting in World War I, and his early enthusiasm for the Nazi Party. During World War II, Gönner served as a teacher in the occupied French Alsatian village of Bartenheim, eventually becoming the town’s Nazi Party chief. As Fatherland follows Gönner to Bartenheim, Bilger creates suspense less from his grandfather’s story than his own efforts to uncover it. His conversations with the elderly residents of Bartenheim, who are eager to share their wartime recollections yet suspicious of their occupier’s descendant, create a rich history of a region over which French and German regimes had battled for centuries.

Yet Bilger’s ability to answer broader questions through his grandfather’s story is complicated when Gönner emerges as a “reasonable Nazi,” rather than a representative one. While he never shies away from his grandfather’s complicity in the Nazi regime, Bilger uncovers evidence in Bartenheim that Gönner exercised his influence to protect the villagers from the worst cruelties of the German occupation. When Bartenheim residents were arrested for draft-dodging or “anti-German sentiment,” Gönner appealed their cases to party officials; at Gönner’s trial after the war, 17 villagers testified in his defense, arguing that he turned a blind eye to men who went into hiding rather than join the army. While people in surrounding Alsatian towns were exiled and executed, no one from Bartenheim was deported in four years of occupation. “In a region crosshatched by cruelty,” Bilger writes, “Bartenheim was an odd blank spot.”

Kinstler takes an entirely different approach, focusing less on her grandfather than Cukurs, his far more famous contemporary. As a result of his extrajudicial assassination, Cukurs has become somewhat of a martyr for Latvian nationalists, and Kinstler deftly illustrates the consequences of his increasing popularity. Some are farcical, like a musical Kinstler describes as an unironic Springtime for Hitler, which glorified Cukurs’ career and suggested that he saved rather than killed Latvian Jews during the Holocaust. (The Latvian Council of Jewish Communities begged to differ.) Others set an alarming precedent for Holocaust denial: In 2019, at the behest of Cukurs’ descendants, the top Latvian prosecutor opened a new inquiry into his case and, disregarding the Holocaust survivors who testified to Cukurs’ participation in mass killings, cleared him of wrongdoing. (Appeals were ongoing at the time of publication.)

Connecting the case to decades of flawed Nazi trials, Kinstler argues powerfully that legal mechanisms alone, especially in countries with a vested interest in denying their Holocaust history, cannot deliver justice to perpetrators like Cukurs. In fact, as in this case, the law can actively participate in the distortion of public memory. But, faced with unyielding archives, she also loses sight of her grandfather: Despite her best attempts, she finds little information about his life, and certainly no verifiable accounts of what he did in the Arajs Kommando or the KGB. The search for Boris culminates in a fruitless interaction with a now-public KGB archive, and he ends up a bit player in a much larger story. Kinstler’s heritage might have piqued her interest in the Cukurs case, but the history she writes is ultimately not so personal.

Of the subjects in these three histories, Schwarz’s grandfather Karl stands out for his very ordinariness. Rather than an enthusiastic Nazi, he was what the Germans now call a mitläufer, or “fellow traveler”: someone who didn’t actively aid the Third Reich but passively acquiesced to it. A consummate opportunist, Karl capitalized on the exclusion of Jews from the German economy in 1938 to purchase a Jewish family’s petroleum products company at a fraction of its actual value. After the war, Julius Löbmann, one of the family’s few survivors, sued Karl for reparations, and their correspondence as they negotiated a settlement offers a queasy view into mitläufer self-justification. Insisting that his purchase of the business was conducted in “the most amicable way,” Karl attempts to outdo the Löbmanns’ suffering with tales of his own family’s misfortunes during the war and even blames Jews for Germany’s dismal postwar situation: “Even if, like most Germans, we did not wish for your fellow-believers’ atrocious fate,” he opines, “from now on we must all suffer for it.” To counter Karl’s claims, Schwarz tracks down a Löbmann descendant living in Chicago, and movingly contrasts her description of the family’s dispossession and flight with the prosperity, civic pride, and even subsidized cruises that her own grandparents enjoyed in the early days of the Reich.

Arguably, Schwarz has the most promising material to work with: The pettiness of Karl’s business acquisition makes him a better analogue for the “ordinary people” who perpetrated the Holocaust than a Nazi Party chief or a member of a notorious killing squad. However, Schwarz exhausts Karl’s history in the first few chapters; the second half of the book, about her maternal grandparents’ lives in Vichy France, relies heavily on secondary sources and is less compelling. She concludes the book with the usual warnings about the far right and exhortations for increased Holocaust education. One doesn’t need a Nazi grandfather to make such prescriptions.

All three books are most compelling when tracing the psychological consequences of a patriarch’s actions. Bilger in particular, who of all the authors had the most positive relationship with his grandfather, explores how the genuine suffering of Germans during and after the war came to obscure Gönner’s Nazism in the family memory. Despite a generations-long silence about the family’s complicity in the crimes of the Third Reich, Bilger finds preoccupation with the past everywhere. It’s evident in his parents’ move from Germany to Oklahoma; in their decision to give their children (with the exception of the author himself) “American”-sounding names instead of the Wagnerian ones popular in their own generation; in his mother’s academic interest in World War II and simultaneous refusal to speak about her own family’s participation in it.

Yet each book also reads like an argument against using one family’s story to “weave together the threads of major and minor history,” as Schwarz sums up the task she’s set herself. Personal histories can serve as steps toward understanding a historical period; but when they privilege individual decisions and motivations over the larger political, social and economic forces at play, they can prove limited. No one person’s life, as Bilger learns when confronting his grandfather’s good and bad deeds, is representative of the systems in which they are enmeshed, and so no one person’s life can show how a society devolved into fascism and how we can avoid doing so in the future. Ironically, by turning away from personal history and towards a narrative about a legal system, Kinstler is most successful at linking the period she investigates to our own political moment.

That’s not to say these books aren’t worth reading, because they are. They show how memory mutates as it is transmitted through generations. They show how families can cling to sanitized versions of their history or resurrect the more difficult truth. In their rigorous yet sometimes anticlimactic journeys through historical archives, they show how many details of our lives, good or bad, are inevitably lost to time. Look to these authors for personal reckonings with a past that is never dead — just not for prophecies about our future.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO