A famous rabbi’s son died of a disease like the one in Broadway’s ‘Kimberly Akimbo’

Rabbi Harold Kushner wrote ‘When Bad Things Happen to Good People’ after his son died of progeria. Here’s why his daughter hasn’t seen the Tony-winning show

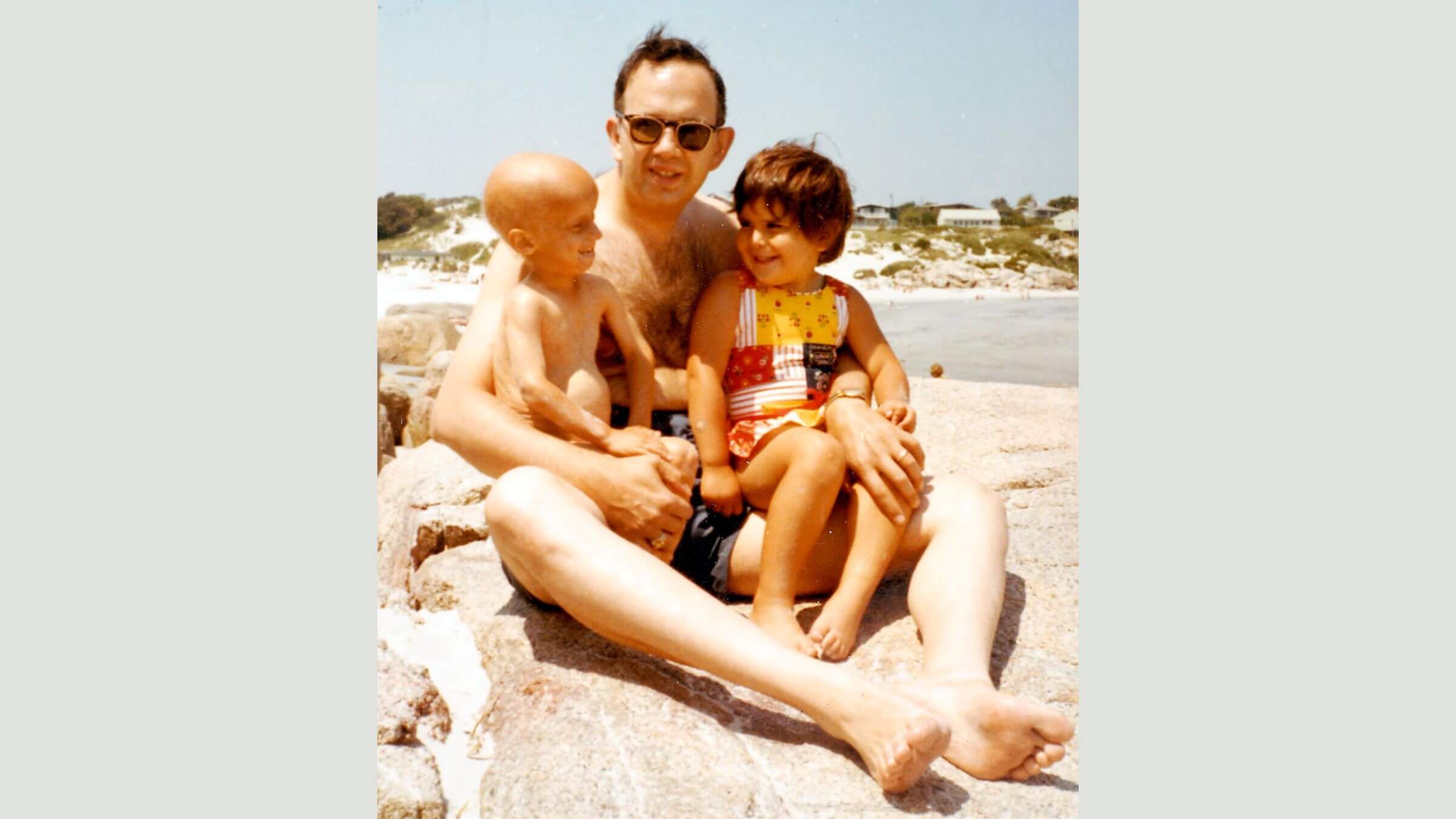

Rabbi Harold Kushner, center, is pictured with his son, Aaron, left, who had a rare disease called progeria, and his daughter Ariel. Courtesy of Ariel Kushner Haber

In the Broadway musical Kimberly Akimbo, Victoria Clark plays a teenager with a rare fatal disease that causes premature aging. Clark is 63 years old in real life, but her character has just turned 16 — the age when she’s expected to die.

Ariel Kushner Haber’s brother Aaron died at age 14 of a real disease, progeria, similar to the fictional one in the show. Aaron’s fate led their father, the late Rabbi Harold Kushner, to write the 1981 bestselling book, When Bad Things Happen to Good People.

But the rabbi’s daughter has no plans to see Kimberly Akimbo, which just won five Tony Awards, including best actress for Clark and best musical.

“I didn’t go to see it and my feelings don’t particularly have to do with the show,” she said in a phone interview. “I’m just very sensitive to people doing any kind of fictional story about children with progeria.”

But “if this brings attention to the disease and makes people think about what these children have to go through on a day to day basis, that is a good thing.”

‘It’s easy to sensationalize’

She added that there’s “a lot of curiosity about progeria. It’s a very interesting disease. It’s easy to sensationalize it or do a story about it that’s really fictional and not based in truth.”

Children with the condition were once viewed as “an oddity, a curiosity or relegated to a circus sideshow,” she said. Sensational characterizations persist, like a recent news story about a baby in Israel with progeria that called the condition “the Benjamin Button disease” — even though the movie Benjamin Button portrays the opposite of progeria, with an old man magically reversing in age to become a baby.

“That’s not even a real thing!” Kushner Haber said. “But these are real children. They have a lot of real issues they’re dealing with. A lot of them do amazing things to adapt. And you have a lot of families doing everything they can to provide as normal a childhood as possible.”

Only 150 known cases worldwide

Fewer than 150 children worldwide are known to have progeria, which is caused by a genetic mutation. It is not inherited and it is no more common in Jews than any other ethnic group. Until recently, most kids with progeria died at age 14, but a relatively new drug, lonafarnib, is extending their lifespans by five years with long-term use, according to the Progeria Research Foundation. The disease is easily diagnosed with a genetic test and can also be detected through prenatal testing.

For such a rare condition, the disease has generated a lot of fictional accounts. A 1991 movie, Jack, directed by Francis Ford Coppola, featured a boy with a progeria-like disease. The producers of a 1984 TV movie starring Ralph Macchio as a boy with progeria sought to buy the rights to the Kushners’ story. The family decided not to cooperate with the filmmakers, but Kushner Haber said she felt the movie borrowed elements from her brother’s life anyway. The movie was called The Three Wishes of Billy Grier, and Kushner Haber said her brother also “had three wishes before he died,” including to meet another child with progeria. In the movie, Billy got all his wishes fulfilled. But Aaron never met another child with his disease because so few had been identified by the time he died in 1977.

The disease in the show

Kimberly Akimbo originated as a play, written in 2000 by David Lindsay-Abaire. In the original script, a character says to Kimberly, “So your disease is like progeria, but without the dwarfism, the beaked nose and the receded chin.”

In the musical, Kimberly and her high school classmate Seth do a presentation about her condition for biology class, and describe the disease in song as “an incredibly rare genetic disorder in which several signs of aging are manifested at a very early age.” But as Seth lists the symptoms, Kimberly regrets the class project, saying it’s “like I’m a slide, I’m a chart, I’m a freak on display.”

There is one depiction on film that Kushner Haber recommends: Life According to Sam, about a real boy who had progeria and his parents, Drs. Leslie Gordon and Scott Berns. “It’s a documentary as opposed to it being a fictional story,” Kushner Haber said. “It’s about a real boy named Sam Berns, and it also follows the science.” The Kushners met Sam’s parents in the 1990s, she said, and helped them found the Progeria Research Foundation.

A spokeswoman for the Progeria Research Foundation, Eleanor Maillie, said the organization has not seen any uptick in donations or inquiries spurred by the Broadway show, but added: “We’re grateful to David Lindsay-Abaire for helping to raise awareness for such an ultra-rare disease, even though progeria is not specifically named.”

Representatives for Kimberly Akimbo and Lindsay-Abaire did not immediately respond to requests for comment for this story. The musical Kimberly Akimbo does not offer a theological take on the protagonist’s fate the way Rabbi Kushner’s book does, but it does include other inspirational themes — like finding meaning in community. The story ends as Kimberly takes a trip with the teenage boy from science class, thereby fulfilling one of her dreams.

Kushner Haber said she hopes that people who love the show will be inspired to help children who suffer from the disease by donating to the PRF to help fund trials and studies that can lead to better treatments. These children are “doing their best to live life to their fullest,” she said.

Missing her father

Kushner Haber’s father died April 28 at age 88. “I’m missing him very, very much,” said his daughter. “He was my dad, but a lot of people feel his loss. He meant a lot to a lot of people. I lost my mom also (in 2022), and my brother, so the fact that a lot of people who feel connected and are sharing their stories is very comforting.”

Kushner Haber, 56, lives in Massachusetts, where her father was the rabbi at Temple Israel in Natick; she owns a business, Muddy Lion Pottery, that features Judaica among other things, and her two adult children are teachers in New York City.

In his book, Rabbi Kushner said he wanted to move beyond “asking why something happened” to “asking how we will respond, what we intend to do now” through compassion, forgiveness and love.

“If you want to believe in God’s goodness and fairness but find it hard because of the things that have happened to you and the people you care about, and if this book helps you do that,” he wrote, “then I will have succeeded in distilling some blessing out of Aaron’s pains and tears.”

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO