His memoir was a transcendent look at Black-Jewish relations. Can he pull it off again — in a great American novel?

James McBride, author of ‘The Color of Water,’ told the Forward about how his family’s story inspired his latest novel — and why writers should stay offline

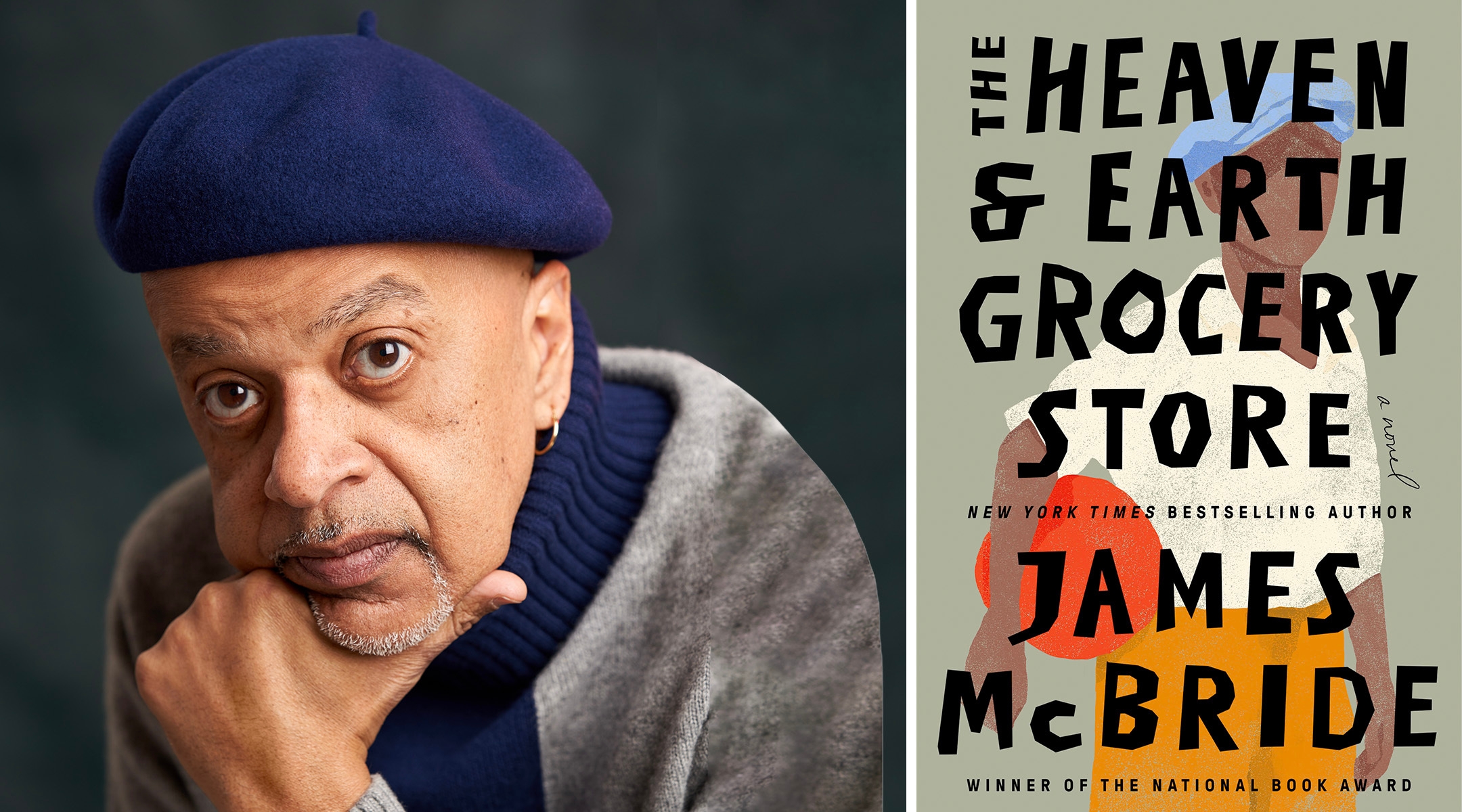

James McBride’s latest novel is The Heaven and Earth Grocery Store. Courtesy of Riverhead Books

James McBride doesn’t own a TV. He hasn’t checked his website in years. He doesn’t go on Instagram. (His account, which is managed by his publisher, has a robust following.)

“I don’t think about what’s going on now when I put a book like this together,” said McBride, whose new novel, The Heaven and Earth Grocery Store, hit shelves this month.

But McBride’s novels tend to speak very clearly to “what’s going on now,” in part because he’s curious about what’s been going on in the past. During a phone interview, he cited William Shirer’s grim 1960 classic, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, as the most influential book he’s read in five years. If McBride’s own books are a bit more optimistic than his reading recommendations, they’re also clear-eyed about America’s brutal past, and the consequences of refusing to understand it.

McBride burst onto the literary scene with his 1995 memoir The Color of Water, which chronicled his upbringing as the child of a Black reverend who died before he was born, and a white Jewish mother whose family shunned and sat shiva for her over her marriage. The eighth of 12 children, McBride grew up in Red Hook’s housing projects, living among neighbors who largely embraced his mixed-race family and pitched in to help his twice-widowed mother.

The author’s interest in personal and national history grounds his meticulously researched new novel. The Heaven and Earth Grocery Store takes place in Pottstown, Pennsylvania, a rural community not unlike the southern towns in which his mother grew up. As the book begins in the 1920s, the town’s Black and Jewish communities live more or less in harmony in the run-down neighborhood of Chicken Hill. They endure linked but distinctly different forms of discrimination from the town’s founding fathers, all of whom seem to believe they’re descended from Mayflower settlers.

When the state decides to institutionalize Dodo, a deaf Black boy beloved in Chicken Hill, in a gruesome mental hospital called Pennhurst, two Jews agree to hide him: Moshe, a scrappy Romanian theater owner, and his polio-survivor wife, Chona. That decision brings drastic consequences — and mobilizes a vast network of people living on Pottstown’s margins, from cranky Yiddish shoemakers to Pullman porters.

The Heaven and Earth Grocery Store shines in its depiction of Pottstown’s many different kinds of Jews, examining the different ways in which educated German businessmen, immigrant housewives and hardened union men navigate their Jewishness in the face of entrenched antisemitism.

I reached McBride, who lives in New York City, in Houston, Texas, where he had just dedicated a reading to the Jewish grandmother he never met. We talked about the real stories that inspired the novel and the vision of solidarity it offers. This conversation has been edited for length and clarity, and be warned — there are spoilers ahead.

You started this book as a tribute to Sy Friend, the director of a Pennsylvania camp for disabled children at which you worked during college. But you ended up writing a very different story about disability and Jewishness. How did that happen?

I wanted to write a book about how Sy ran things, and how he taught us so many important lessons. But every time I wrote the chapters, they were really corny and didn’t feel real. You can’t drape a novel around the regiment of a camp day. You’re stuck with the whole business of it’s morning, there’s breakfast, they’re going on a hike. Sy’s heroism is not easy to place on the page. But the way he dealt with matters is typified by the wider story of this town.

How did you land on Pottstown as the setting for this story?

It was an accident. I wanted it to be Pottsville, because it’s close to Pittsburgh, where the dynamic of Black-Jewish relations was much more evident and better documented. But then I was going to see Pennhurst and I saw a sign that said “Pottstown,” so I drove into town. Pottstown is worn out, it’s not what it was, but it’s physically beautiful. I went to the historical society, I went to the library, and I started talking to people in town. I learned about Chicken Hill, and the synagogue that was there. The current synagogue shares space with a Black church. So it seemed like a logical place to set the story.

One thing I admire about The Heaven and Earth Grocery Store is its commitment to depicting the many complicated subgroups within Pottstown’s minority communities. The novel is brimming with characters who represent different ways of being Black or Jewish in America. Why was that important to you?

I’m sick of the dissension that happens when the word “Black” or “Jew” appears in a sentence. It’s really detrimental to where we need to be right now. Despite all our differences, there’s plenty of common ground. What I tried to do in this book is show how people simply excused a lot of those differences, set them aside for the moment, and got to the business of finding the meal that would feed us all. I just wanted to show in this book that we have gotten along very well. We have got to stick together and deal with the reality of where we are. We’re in deep water, and we will end up in deeper water if we don’t pay attention.

Intra-communal conflicts and prejudices really animate this novel. How did you figure out, for example, the contemporary stereotypes about Romanian theater owners?

I just read a lot. There are lots of first-person accounts of Jews who came here from Eastern Europe and how they dealt with one another. Some of the attitudes that prevailed at the time I learned from my mother. The Romanian theater owners — well, that’s just how it was in Pennsylvania. My understanding is that they were really hard people, because they lived a hard life in Europe. Despite that, they were generously kind when it came to poor people, because they understood suffering.

How much did you draw on The Color of Water when writing this novel, and what do you want readers to learn from your own personal history?

When I researched The Color of Water, I was much younger. I had hair on my head. And when I went to Suffolk, Virginia, I was shocked by some of the stories old Jewish people told me. The signs that said, “no dogs, no Jews, no n-words” — that was real. As a young man, I didn’t really understand how deep antisemitism ran. The sense of history in this country is really short. People’s memories are really short. We should study history more.

Many Chicken Hill residents, especially the Jewish ones, want to assimilate into Pottstown’s white Christian culture in order to achieve the “American dream.” Are they doomed to lose sight of their own traditions and heritage in the process?

These are the cultural questions we’re going to grapple with as long as we live. When you move into the larger society of American life, and accept the so-called “American existence,” what part of that is a sweet piece of candy? And what part is a sour lemon? How much money do you need to live? How big does your house need to be? How much of the American life is really good for you, as opposed to the rich cultural things that helped you survive for hundreds of years?

Critics are already dubbing this book the next “Great American Novel.” What do you think about that?

If I thought I was sitting down to write the Great American Novel, I could never do it. I’m not that smart. I just wanted to write a good story that touched on things people don’t know much about.

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly identified the publication date of McBride’s memoir. It was 1995, not 2006.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO