In the shadow of death and motherly disappointment, Albert Brooks changed the world of comedy

In a new HBO documentary, Rob Reiner pays tribute to his best friend Albert Brooks

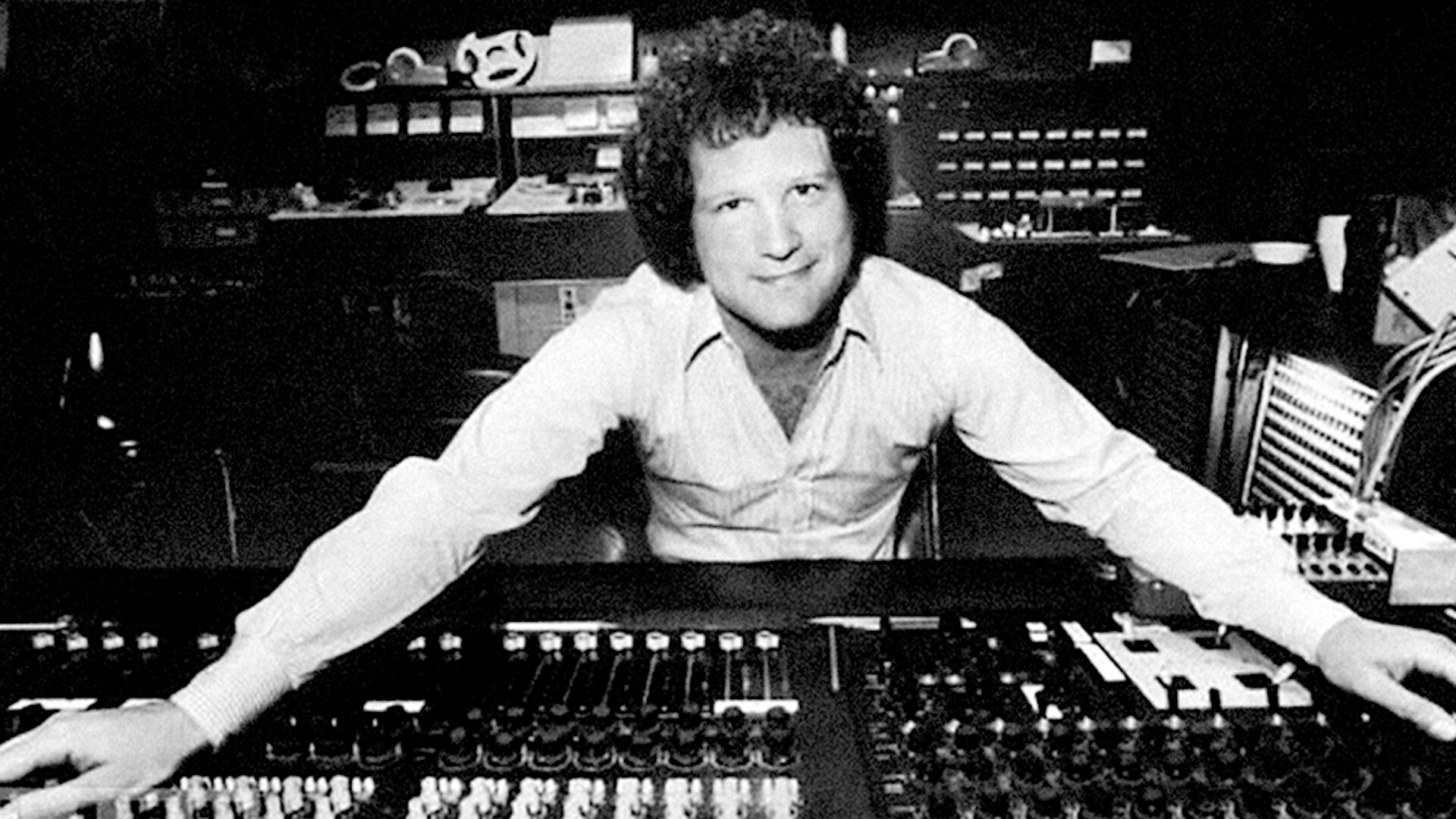

Albert Brooks. Courtesy of HBO

Albert Brooks thinks, or hopes, death will be like the deep sleep of a colonoscopy —“a big one.”

Over cheesecake at a white tablecloth restaurant, the comedian is kibbitzing with his friend of over 50 years, Rob Reiner. The conversation covers Brooks’ beginnings as a forerunner of alt comedy, his transformation to auteur and his turn as the voice of a cartoon clownfish, but the main grace note is mortality. Though at the end of the session, Reiner quips that Brooks was defending his life, there’s not much he did that needs defending, even if there’s a sense of urgency for a living tribute.

Albert Brooks: Defending My Life, on HBO Nov. 11, clarifies just how much of Brooks’ oeuvre was shaped by death.

When Brooks was 11, his father, Harry Einstein, who performed in film and radio in the persona of Parkyakarkas, famously died on the dais of the Friar’s Club after giving a sidesplitting roast of Desi Arnaz and Lucille Ball. He had been ill since Brooks (né Albert Einstein) was born.

1991’s Defending Your Life, which Reiner’s title riffs on, came out of Brooks’ long preoccupation with the afterlife following his father’s early exit. That film, which involves Brooks reviewing footage of his cowardly acts on this mortal coil to make a case for his place in the hereafter, had a companion piece in a 2021 episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm, where Brooks staged a memorial service for himself, which he watched remotely from his bedroom TV like a 21st-century Tom Sawyer.

Brooks’ father’s passing was so sudden that the immediate tribute was crooner Tony Martin singing his hit “There’s No Tomorrow.” Brooks’ brother Bob Einstein had his own HBO documentary that aired after his death in 2019. While Brooks is still with us, Reiner has made a beautiful ode to his genius friend with a who’s who of celebrity admirers.

Anthony Jeselnick and Jonah Hill liken Brooks’ talk show antics, where he’d skewer hokey novelty acts endemic to variety shows, to punk rock. David Letterman claims he’d prefer Brooks’ career to his own. Ben Stiller says that, when he was unsure of a woman he was dating, he would test her taste in film with a screening of Real Life. Sarah Silverman credits him with giving Saturday Night Live rotating hosts and pre-taped segments, and Alana Haim is so smitten she hints she may one day get a tattoo inspired by Lost in America.

While Reiner’s movie is a love fest, it is also a light therapy session. Brooks explains his withholding mother, who could only validate his talent if Johnny Carson did so first — or until his Oscar nomination for Broadcast News (see Brooks’ Mother for more of this dynamic). Harry’s early death led to a detachment that belatedly surfaced in a nervous breakdown after Brooks played a show in Boston.

Brooks was able to handle most of his issues, massaging them into beloved and critically celebrated films, though, he says, the studio insisted Modern Romance add a scene with a therapist or lose its advertising. (On that note, we learn, Stanley Kubrick called Brooks to say the studio was in the wrong and asked how Brooks made the movie about jealousy Kubrick always wanted to. Brooks’ response: “How did I do it? How did the guy walk upside down in 2001?”)

Throwing a spotlight on Brooks’ long career, which, since 2005, has shifted almost entirely to acting, including an against-type role as a murderous heavy in 2011’s Drive, the documentary is worth watching for the clips of films and late night performances. If you like Rob Reiner and Brooks — and who doesn’t? — seeing them chat has its own delights.

The analysis of Brooks’ comedy is left to comedians and fans, and is lacking some critical insight into just how disruptive and refreshing his avant garde approach was. At one point, all Larry David can offer is “I saw Real Life and I thought, ‘Oh, you know, this guy, he’s really special.’”

Defending My Life makes no bones about being a love letter from one friend to another, and for that reason it may appeal most to those who already are fond of Brooks’ work or are interested in some of the wacky backroom deals behind it, like the time Warner Bros. floated the idea of releasing Looking for Comedy in the Muslim World on JDate.

While it misses being much more than a fawning profile of a man widely beloved, the greatest service it offers is a reminder to appreciate and revisit Brooks’ work. That’s a great thing. He shouldn’t have to wait for the Big Propofol Sleep to earn it.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO