How New York’s male Jewish intellectuals are still shaping our politics and culture (for better and worse)

Two new books and a documentary about Norman Mailer argue the continuing relevance of Jewish men who tried to secure their place in postwar America

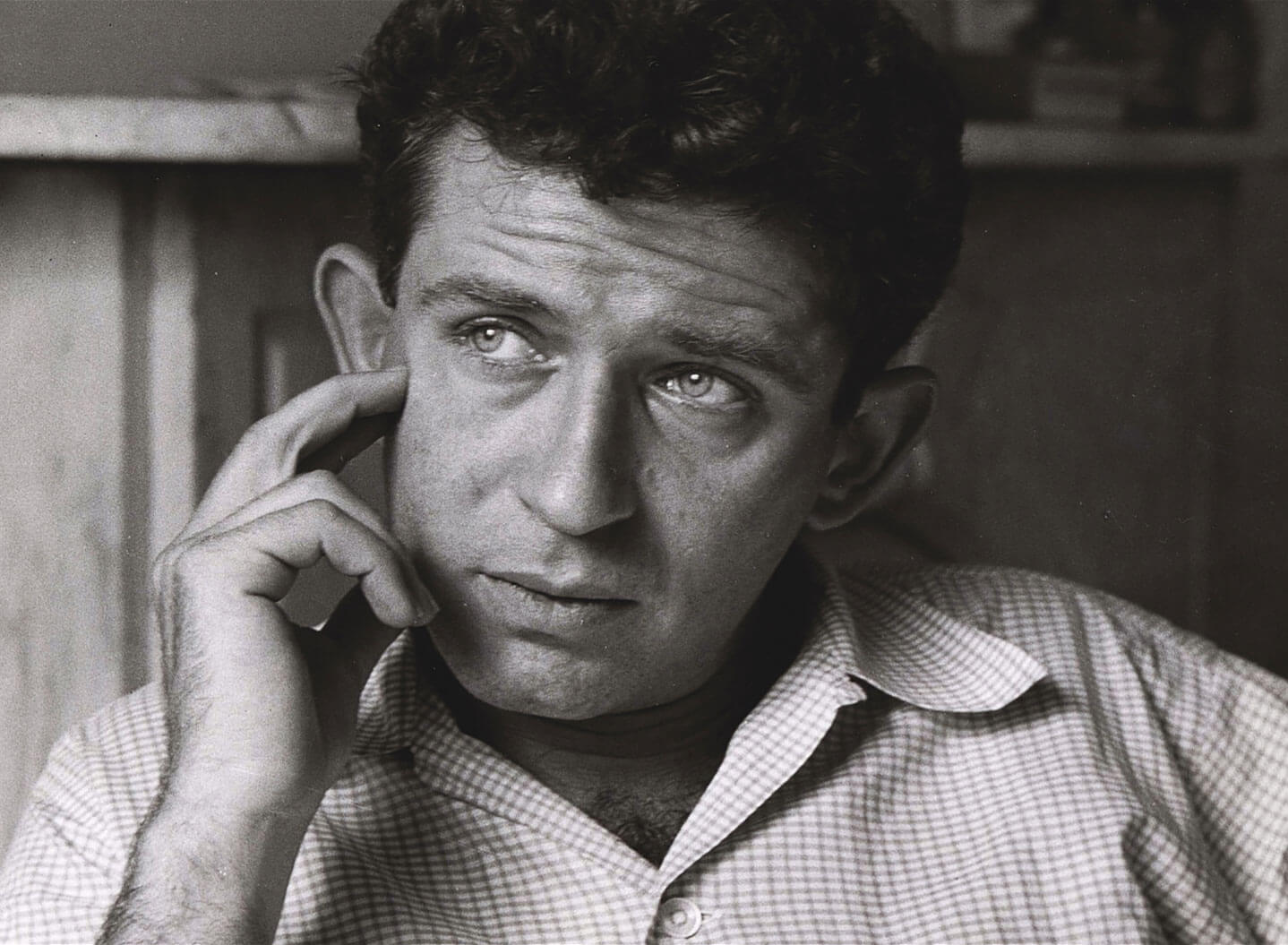

The title figure in Jeffrey Zimbalist’s documentary “How To Come Alive With Norman Mailer.” Courtesy of Zeitgeist Films

In Arguing the World, the 1998 documentary about Jewish men who helped define postwar intellectualism and politics, Diana Trilling muses, “Unless a man in that community was bent on sexual conquest he was never interested in women.”

A new documentary, How to Come Alive with Norman Mailer, by director Jeff Zimbalist, and two new remarkable books, Write Like A Man, by the historian Ronnie Grinberg, and The Freaks Came Out to Write, an oral history of the Village Voice by Tricia Romano, show the enduring legacy of this group of men’s quest to configure a new secular Jewish American masculinity. From the most earnest journalism, to the more cynical think piece and omnipresent snark, we are living in a landscape shaped by these individuals’ need to secure their place as American men.

In her utterly compelling book, Grinberg gives full life to Diana Trilling’s lament. She provides a vibrant portrait of these men and their orbit, showing how their pugnacious intellectual fervor was shaped by a need to forge an American male identity from the material of their second-generation Jewish experience.

Her subjects include not only the Arguing the World quartet – Irving Howe, Irving Kristol, Daniel Bell and Nathan Glazer — but also Norman Podhoretz, Phillip Rahv, Lionel Trilling, and the troika of Jewish novelists who wrote Big Books about America and masculinity – Norman Mailer, Phillip Roth and Saul Bellow. Of course, this cast “allowed” for the mostly supporting roles of some women because they were able to perform secular Jewish masculinity and make up for being “lady writers.” Susan Sontag, Hannah Arendt, Diana Trilling, Cynthia Ozick and very few others sufficiently fit the mold of the secular Jewish New York intellectual ready to do battle over cultural criticism and strident political polemic.

Grinberg makes a convincing case for how these sons of immigrants melded their parents’ educational aspirations with the Talmudic traditions and radical politics that permeated the Jewish world of the early to mid 20th century. Many Jewish immigrants famously traded their religious ideology for a secular one – especially when faced with inhumane working and living conditions and the palls of racism, antisemitism and other systemic scourges of their newly adopted home. However, the next generation wanted to distance themselves from a blinkered embrace of the Soviet Union and an undereducated and beleaguered social standing. The devastations of the Depression only further diminished their hardworking Old-World-accented patriarchs.

As a result, these new strivers would form the vanguard of the robust, cerebral, anti-Communist liberal left.

“The New York intellectuals helped render American Jews, a group long associated with left-wing radicalism, as not only properly anti-communist but properly masculine in Cold War America,” Grinberg writes.

In 1937, the Partisan Review relaunched, severing any ties to the Communist Party and synthesizing anti-Stalinism and modernism. This commitment to a specific politics, and the elevation of culture as integral to understanding it, would form the mold for the New York Intellectuals and ultimately for American intellectualism itself. Commentary, founded in 1945, by the American Jewish Committee, was another manifestation and tool of this secular Jewish American male project (the name itself connotes the tradition of Talmudic discourse, that sacred practice carried out by men for men). Encounter, The New York Review of Books, Dissent, and other publications would soon follow, helping cement this new American male ideal of intellectual vigor and hard-won liberal patriotism.

Perhaps not surprisingly, Zionism was not part of it. At least at first. Although David Ben Gurion was establishing his own project for the new Jewish man much around the same time, the New York Intellectuals were adamantly American. That was the whole point. “Commentary was initially cold toward Zionism,” Grinberg writes, “since it raised the specter of dual loyalty and implied that America was not a home for Jews.”

If Howe, (Norman) Podhoretz, and (Lionel) Trilling are the elders most closely associated with the origins of this new secular Jewish masculinity, the novelists and younger generation arguably took it to its most extreme expression. To many, Norman Mailer, the subject of the new documentary by Jeff Zimbalist, represents its apotheosis – almost its id — wrestling not only with ideas, but infamously with actual people.

How To Come Alive with Norman Mailer mostly serves as a reminder of Mailer’s nearly cartoonish machismo. It certainly provides a handy highlight reel – with some insightful commentary from a cast of notables and also his many children and remaining wives (it seems to have gotten the blessing of everyone alive related to him and suffers for it; at times it feels like a pat eulogy). It does however clearly show how Mailer’s nearly desperate “man-of-action” persona sprang from his desire to overcome a more meek and cerebral Jewish upbringing. Mailer “always wished he could be the tough guy and he did that in his writing,” one of the narrators says, adding that Mailer “wanted to be the new Hemingway — a combat soldier in life rather than in war.”

The film makes the case that even Mailer’s womanizing was a rebellion against his Jewish upbringing. Yet, even though he once actually stabbed his then-wife, the movie mostly extolls his virtues as a risk-taker and gleeful gadfly, as the public intellectual unafraid to provoke and stick his thumb in the eye of polite society. Both books and the film, understandably, showcase the famous 1971 Town Hall event when he was asked to moderate “A Dialogue on Women’s Liberation.” The panel included three feminists: Jackie Ceballos, president of the New York chapter of the National Organization of Women; Jill Johnston, a radical lesbian and the Village Voice dance critic; and Germaine Greer, the Australian author of The Female Eunuch.

Not surprisingly, many feminists were less than interested in sharing a stage with Mailer. Gloria Steinem and several others refused to even attend and Ellen Willis, a Village Voice contributor and one of the founders of the women’s liberation group Redstockings, dropped out at the last minute. Despite participating, Johnson says in the Voice oral history: “Just to appear at town hall (sic) was to acknowledge Mailer. And to concur in the tacit premise of the occasion: that women’s liberation is a debatable issue. In this sense…it was a disaster for women. As a social event, it was the victory of the season.”

Indeed, many relished the spectacle and the public debate. The audience seemed to include the entirety of New York intelligentsia. Sontag famously took issue with Mailer after he introduced Diana Trilling as a leading “lady” critic, telling him and the assembled crowd, “If I were Diana, I wouldn’t like to be introduced that way. And I would like to know how Diana feels about it. I don’t like being called a lady writer.”

Much of the Q&A session was dominated by the “ladies” in the audience whose sharpness and levity helped undermine the event’s attack on feminism. Memorably, Cynthia Ozick asked, “Mr. Mailer, when you dip your balls in ink, what color do your balls become?” Grinberg casts Ozick’s comment as performing the kind of Jewish masculinity that gained her acceptance among the New York Intellectuals.

In this way the evening portended new confrontations: between not only Mailer and the assembled feminists, but between unapologetic feminists like Greer and Johnston, and those like Sontag and most of the women of the New York Intellectuals circle, who did not wish to associate themselves with the new movement.

Mailer often took the remaking of the American Jewish male to one of its most grotesque extremes. However, it also led to a more fully embodied style of writing, helping form a foundation that could propel other voices. New Journalism is usually recalled as the province of male journalists and novelists, such as Hunter S. Thompson and Tom Wolfe, Gay Talese, but it also emancipated many other writers – elevating the personal, and individual style, to foreground “serious” stories. In this way, Mailer would become a very unlikely bridge between several worlds.

The Village Voice, which Mailer co-founded, was a natural inheritor of the New York Intellectuals’ brand of political, cultural and ideological inquiry. However, this time, with women ultimately “Writing like Women” (i.e. writing in their own voice and from their own experience). Unlike the coterie of female writers both doing battle and collaborating with the New York Intellectuals, the women at the Voice pioneered an explicit and unapologetic feminist journalism.

“Those were the days when I was on the barricades for radical feminism, and I saw sexism everywhere,” Vivian Gornick says in the oral history, adding that the Voice’s embrace of personal journalism allowed her to write articles that called out sexism.

Of course, the women at the paper still had to contend with the macho and sexist writing culture that pervaded the Voice where many men aspired to an even more vigorous ideal of the writer as a man of virile excess – the carouser, the fighter, the indignant moralizer – looking down at anyone who was not white, straight and doing investigative journalism.

Even so, the Voice became a bastion for serious feminism, for writers of the Second Wave such as Susan Brownmiller, Gornick, Johnston, Willis, and others. Its ranks also included the fearless Mary Nichols who helped square up against the bulldozer that was Robert Moses, and even helped Robert Caro with his first cache of “smoking gun” documents against the mighty powerbroker.

The Voice helped form some of the most important critical voices in culture today, including Manohla Dargis and Roberta Smith and editor Lisa Kennedy, women who did not hesitate to use a feminist lens in their reviews, a practice that is now so completely integrated it is taken for granted. The Voice always provided a fertile and fraught proving ground, with an outpouring of some of the best investigative and cultural writing that has permanently permeated journalism. While the late Greg Tate and others may seem like sui generis voices from another planet, The Voice gave them the platform for full flight.

The living legacy of the New York Intellectuals may seem most obvious in this ultimate normalization of the subjective voice and experience and the now undisputed place of culture as an important lens on society. In the last several years, it has also proven even more directly influential with the advent of such publications as The Drift, The Los Angeles Review of Books, n+1, The New Inquiry, Jewish Currents, and podcasts like Know Your Enemy, and the Brooklyn Institute of Social Research, which have all taken on the project of serious intellectual inquiry coupled with a desire to create a just society. And like the OG crowd, these serious quarrels with the meaning of history and the present moment also devolve into nearly farcical ego-driven heel-digging such as the “Is it Fascism?” debate that has invaded almost every inch of any written word, from Twitter to serious academic anthologies, with some unseemly petty backbiting.

Other echoes abound of the worst aspects that Grinberg makes plain – men being serious with other men, sparring with other men, while allowing for women they hold in high enough esteem to be included in their ranks. And the legacy also includes another branch — neoconservatism and its progeny, with its influence on policy that will reverberate for generations.

While the neocons may seem to be in the rearview mirror of the rabid GOP movement today, their obsession with liberal hypocrisy certainly helped set the stage for it. Trolling liberals has become one of the central and unifying forces of the right wing, arguably its main ideology.

The evolution of the CCNY crowd and their peers and proteges provide an arc to how we have arrived at our current discourse. Grinberg’s and Romano’s books are essential reading for understanding where we are today, along with being just brilliant reads and histories. Much is made and memed about “Men would rather (fill in the blank) than go to therapy.” These Jewish men’s anxiety about finding an unimpeachable American identity is clearly a mixed legacy.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO