Judaism is a “silent character” in Nora Ephron’s legacy

“Nora Ephron at the Movies” explores film, fashion and food. Ephron’s Jewish identity? Not so much

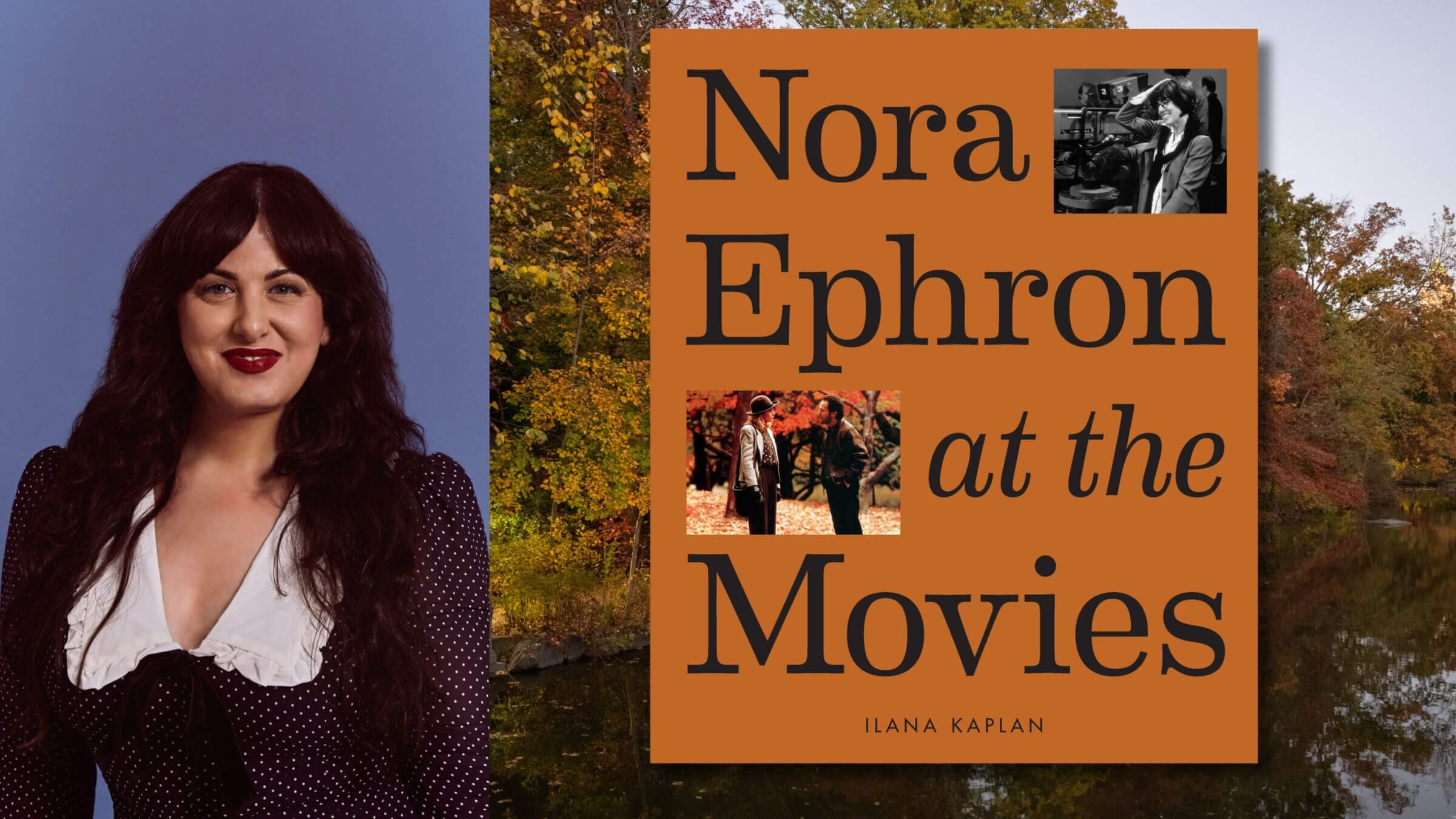

Journalist Ilana Kaplan (pictured left) with her upcoming debut book, Nora Ephron: At The Movies. A Visual Celebration of the Writer and Director Behind When Harry Met Sally, You’ve Got Mail, Sleepless in Seattle, and More. Photo by Samuel Shepherd/Canva/Alexi Rosenfeld/Getty Images/headshot and book cover courtesy of Ilana Kaplan

Ilana Kaplan’s new book Nora Ephron at the Movies talks about the idea of “comfort” 21 times.

That makes sense. “Comfortable” describes the aesthetic of Ephron’s films: cable-knit sweaters, oversized jeans, a city somehow perpetually in autumn. Ephron’s rom-coms with strong female leads have nourished generations of movie-lovers and are often called “comfort films.”

In contrast, the word “Jewish” appears only three times in Kaplan’s book, and twice just to describe a certain deli that acts as the setting in one of Ephron’s most iconic scenes. The book focuses on Ephron’s impact on the world of film, not the writer-director’s Jewish background.

That’s true to real life. As those who knew the late Ephron personally attest, Ephron’s Jewish identity was something that indeed textured her life and films, but it was by no means the center of her work, nor did she want her background to define her.

“She wanted to be known as a director, and not a female director and not a Jewish female director,” said Abigail Pogrebin, a journalist and friend of Ephron.

Pogrebin profiled Ephron for her 2003 book, Stars of David: Prominent Jews Talk About Being Jewish. In the book, Ephron shares how she was raised by nonobservant parents who had “contempt” for religion, but she still came to embrace a more cultural interpretation of Judaism later in life.

“In terms of ritual observances and synagogue-time, no, I wouldn’t describe Nora as an observant Jew in the traditional sense,” Pogrebin told me over the phone. Ephron’s family celebrated Christmas, and she got a D in her college bible course.

But to Ephron, Judaism was “completely part of her gestalt, her prism,” Pogrebin said, and Ephron was open about her Jewish identity throughout her career.

A sacred text of Ephron lore

This autumn, 12 years after the beloved screenwriter and director died, Kaplan is revisiting Ephron’s lasting legacy in a glossy, gushy new illustrated book.

In effusive prose, Kaplan delves into Ephron’s entire filmography, as well as her essays and other writings. There’s the holy trifecta of Meg Ryan rom-coms that Ephron either wrote or directed; When Harry Met Sally, Sleepless in Seattle and You’ve Got Mail all earn their own chapters.

There are also sections detailing some of Ephron’s lesser-known films, such as the Christmas movies Michael and Mixed Nuts. An entire section at the back showcases one-on-one interviews with Ephron’s professional collaborators.

The book also displays grand photographs on each page. There are film stills from Ephron’s movies, and from the many modern rom-coms that her work inspired. The pictures of Ephron, often in black and white, give a glimpse into the life of a complicated, trailblazing artist.

“As a Jew but not Jewish”

But for all the painstaking research Kaplan puts into describing Ephron’s food preferences and her iconic fall fashion sense, the book does not engage with Ephron’s Jewish identity. Kaplan said that was because Judaism informed Ephron’s work in a much more understated way.

“In her life, it was just like a kind of background in a lot of things,” Kaplan explained. “There’s a quote that she identified as a Jew, but not Jewish,” she said.

Kaplan is a culture journalist who has written for The New York Times, Rolling Stone and NPR. Nora Ephron at the Movies is her first book. Like Ephron, Kaplan said she resonated with more cultural interpretations of Judaism than religious ones.

“There are aspects of Christmas involved in all of those movies,” Kaplan said, referring to films like When Harry Met Sally and Sleepless in Seattle. “And I’m a Jew who has always loved Christmas!”

In the rare instances where explicitly Jewish characters appear in Ephron’s work, the portrayal can be self-effacing. Kaplan cited Ephron’s novel Heartburn, where protagonist Rachel Samstat discusses how she can detect a spoiled “Jewish prince” in three words: “Where’s the butter?”

Similarly, there are no outwardly Jewish protagonists in Ephron’s romantic comedies, but “the Jewishness comes through in some of the characters’ attributes, or their neuroses,” Kaplan said.

The religion of romantic comedies

Kaplan’s writing process had all the chaos and whimsy of a Nora Ephron script itself. She shared how she researched and wrote the book over two years while simultaneously working full-time and planning for her wedding, which meant meticulous scheduling and coordinating with her partner.

“It was a lot, but it was also kind of magical,” Kaplan said.

Kaplan said that Ephron even earned a shoutout in her wedding vows.

“With tears streaming down my cheeks, I gushed about how much rom-coms, specifically Nora’s trio of groundbreaking genre films, had shaped my core beliefs of finding true romance,” Kaplan writes in the book’s afterword.

Watching some of Ephron’s films over Yom Kippur weekend, I found myself on the lookout for details that clued into Ephron’s Jewish background. The jilted husband in Sleepless in Seattle seemed Jewish-coded, but only because of his allergies. The food in Julie & Julia made me salivate, but Julie’s boeuf bourguignon was a far cry from Rosh Hashanah brisket.

Ultimately, I found in Ephron’s films a distinctly Jewish-American sensibility, one that values feisty dialogue, warm characters and a brainy sense of humor over any particular Halakhic ritual. And maybe that’s the key to understanding Ephron’s Jewish particularities, and also her films’ broad-reaching, intergenerational appeal.

Kaplan shared this sentiment. She likened Judaism to a “silent character” in the background of Ephron’s films that manifested in “broader strokes.” Kaplan added that as a more cultural Jew herself, she also felt a kinship with Ephron’s secular, but unapologetic brand of Judaism. She saw Ephron as an inspiration.

“I worship this director who’s Jewish, and that makes me feel like it’s a cultural connection,” Kaplan said. “I might not go to the temple, but I believe in the religion of Nora Ephron.”

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO