(New York Jewish Week) — Musicians often mine their pasts for inspiration. But Brooklyn-based Jewish singer Laura Elkeslassy went back generations to create her new album, “Ya Ghorbati: Divas in Exile,” doing a deep dive into the history of her Moroccan Jewish family.

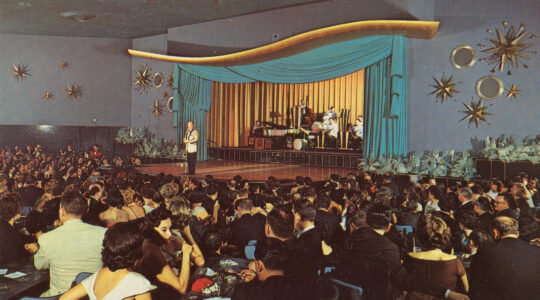

What she discovered were songs of North African Jewish singers, mostly women. “There was a tradition of ‘divas’ in North Africa in the early 20th century. Interestingly Jewish female singers were very present in the music scene at the time,” Elkeslassy told the New York Jewish Week.

“The album looks across time and space to tell a tale of political upheaval and exile,” she continued, “ultimately questioning the binary between Arab and Jew.”

Elkeslassy, 37, and her bandmates recorded the album, which is her first, live last June on the streets of Park Slope, at the invitation of the Brooklyn Conservatory of Music in honor of World Refugee Day (June 20). “We really wanted to offer the music to the community as soon as the city reopened,” she said. “The whole block joined the concert. It was a true communal experience.”

And now, as World Refugee Day approaches again, she’ll perform songs from the album on Wednesday, June 15 at Congregation Beth Elohim in Park Slope.

The concert, co-sponsored by CBE’s New Jewish Culture Fellowship and the publications Ayin Press and Jewish Currents, is emblematic of a wave of Jewish cultural events that aim to reach beyond the Ashkenazi New York Jewish culture stereotype. (This writer first encountered Elkeslassy when she performed at a Mimouna celebration at Wild Birds, a trendy dance joint and bar that opened in Prospect Heights in 2020.)

“Laura entertains masterfully,” said Rabbi Matt Green, a rabbi at Congregation Beth Elohim and the co-founder of the New Jewish Culture Fellowship. “But she also leaves audiences interrogating their own cultural inheritances as they pursue Jewish meaning in their own time.”

Elkeslassy calls “Ya Ghorbati” a “multimedia album” because the project weaves together music, videos and essays on the stories behind each song. The album originated as a collaboration between Elkeslassy and music director Ira Khonen Temple, who were inspired to develop the project during the pandemic. “For a year, Ira and I researched the material and rehearsed it in my Park Slope backyard, through heat waves and icy weather,” she said. “Some neighbors enjoyed the free concerts. Some cursed their fate that they were stuck working at home next door to a singer.”

Among the singers honored in “Ya Ghorbati” are Zohra Elfassia, who was revered as the greatest Moroccan diva of her time; Line Monty, who wove together French cabaret and classical Andalusian music; and Salim Halali, a gay male performer who owned three cabarets in Casablanca and Paris.

“The divas presented in the album were feminist trailblazers, finding joy, freedom and power in a sometimes hostile cultural landscape,” Elkeslassy explained. “I was fascinated by how, in their own unique ways, and with their own contradictions, all of these artists dealt with the powerful forces that changed their time and careers: patriarchy, colonialism, the rise of Jewish and Arab nationalisms. I was curious to understand how those forces had shaped their lives, and with them, the lives of their generation and of my parents’ generation.”

Creating the album was an opportunity for Elkeslassy to discover the music of her ancestors. “My mom was born in Fez and my dad was born in Marrakech,” Elkeslassy said. “My family was in Morocco for centuries. That’s really what I was exploring; I wanted to understand where I was coming from.”

Support the New York Jewish Week

Our nonprofit newsroom depends on readers like you. Make a donation now to support independent Jewish journalism in New York.

Elkeslassy grew up in a Maghrebi (North African) Jewish community in the upscale 16th arrondissement of Paris, a place she describes as “very bourgeois — the equivalent of the Upper East Side.”

She left Paris to attend acting school in New York 14 years ago and never left. “I wanted to come here to reorient myself to what I always wanted to do, which was art, music, theater,” she said. “What’s ironic is that the distance allowed me to come back to my own community, in music.”

Elkeslassy grew up hearing Moroccan melodies in synagogue, at weddings and other celebrations. But when she moved to the States, she found her Sephardi American friends had mostly been raised in Ashkenazi communities and, as she puts it, “didn’t have access to their own heritage.”

Her album aims to correct this. “It’s an attempt to offer this music back to ourselves,” she said. “Some folks are very familiar with it. Some have been disconnected from it, because they have grown up in Ashkenazi environments and didn’t necessarily have access to their own liturgical or musical traditions that are rooted in Arabic music.”

She also hopes the album will help bring awareness to the American Jewish community about the history and culture of Jews with Arab backgrounds more broadly. “Too often, the mainstream political and cultural discourse erases that history, particularly in the U.S.,” she said. “It’s important that the Jewish community become more aware of not only the presence of Sephardi/Mizrahi Jews but also of how American Jewish institutions have, very literally, affected the lives of thousands and thousands of Jews in Arab lands over the last century.”

Even in France, the Judeo-Arabic musical tradition isn’t necessarily being passed on from one generation to the next. When Elkeslassy’s sister was planning her wedding in 2016, Elkeslassy feared no one would sing “Abiadi Ana,” a song traditionally sung by the bride’s oldest woman relative during the henna ceremony (a Moroccan marriage ritual). “I remember my grandmother on my dad’s side singing it at my cousin’s wedding,” Elkeslassy said. “But when my grandmother passed away, nobody knew the song anymore.”

In fact, no one had sung it at Elkeslassy’s own henna ceremony the year before, and she was determined someone would at her sister’s.

Elkeslassy began a hunt to find someone to teach her the ritual melody. Finally a member of the New York Andalus Ensemble, a local Maghrebi music ensemble with whom Elkeslassy had begun performing, revealed he knew the song, and taught it to her. Elkeslassy surprised her family by performing it at the henna. “The older generation were all crying,” she said.

“Abiadi Ana” (“I Am Happy”) is now included on Elkeslassy’s album. Soulful and melodic, the song starts slow and then kicks in with percussion and a lot of personality from the oud, accordion, violin and bass. Based on the version by the diva Elfassia, it somehow sounds both haunting and joyful.

“Ya Ghorbati” is arriving at a time when an evolving understanding of colonialism and race are reshaping the perspectives of many Americans — the Jewish community very much included.

“It’s not only about the songs,” said Edwin Seroussi, a musicologist and scholar of North African, Middle Eastern and Israeli music at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. As he explained, Elkeslassy’s project draws upon the often ignored historical contributions of women Mizrahi singers. The project is also emerging during a time of growing awareness in America that Jews are not only Eastern European, a fact that is much more obvious in Israel, whose Jewish population is about 50% Mizrahi and Sephardic Jews. (In contrast, the Jewish community in the United States is predominantly Ashkenazi.)

“That Mizrahi presence in Israel became very influential in intellectual circles, in politics, etc., and that revolution eventually reached American shores,” he said. “It’s about claiming or reclaiming their culture as being underestimated or ignored. Many American Jews don’t even believe that there are Jews who speak Arabic as a mother tongue.”

Support the New York Jewish Week

Our nonprofit newsroom depends on readers like you. Make a donation now to support independent Jewish journalism in New York.

Elkeslassy herself sees the work as a way to bridge the rupture she feels between her Jewish and Arab identities. “It’s a way of saying, you know what? We’re also Arabs, actually, and we forgot about that,” she said. She’s part of a broader global trend of reclaiming Mizrahi and Sephardic roots through music, like the Israeli Yemenite sisters A-Wa and the Israeli Moroccan singer Neta Elkayam, who was a prime inspiration for Elkeslassy.

After her Brooklyn concert, Elkeslassy hopes to tour with her album more broadly throughout the U.S. and abroad. But for New Yorkers looking for more ways to experience local Mizrahi and North African culture, Elkeslassy has some recommendations for where to begin. Start with eating at the Persian restaurant Sofreh in Prospect Heights, attending a performance by the Arabic music group Brooklyn Maqam, and checking out the Algerian belly dancer Esraa Warda. And, of course, order a tagine at the Moroccan restaurant Cafe Mogador, which has locations in Williamsburg and on St. Marks Place in the East Village.

“When I was living in Manhattan I established my headquarters there,” she said. “I was like, this feels like home.”

You can reserve a free ticket for Elkeslassy’s Brooklyn concert at Congregation Beth Elohim on June 15 here. Additionally, she’ll be teaching a virtual class with our partner site, My Jewish Learning, about Salim Halali — a gay, Jewish Algerian superstar, whose work is featured on Elkeslassy’s album — on Thursday, June 23 at 2 p.m. Find details and registration link here.