Incredible exhibit highlights Jewish medical students in 16th century Italy

The exhibit in Padua includes a Yiddish translation of a treatise on human anatomy and illustrated diplomas.

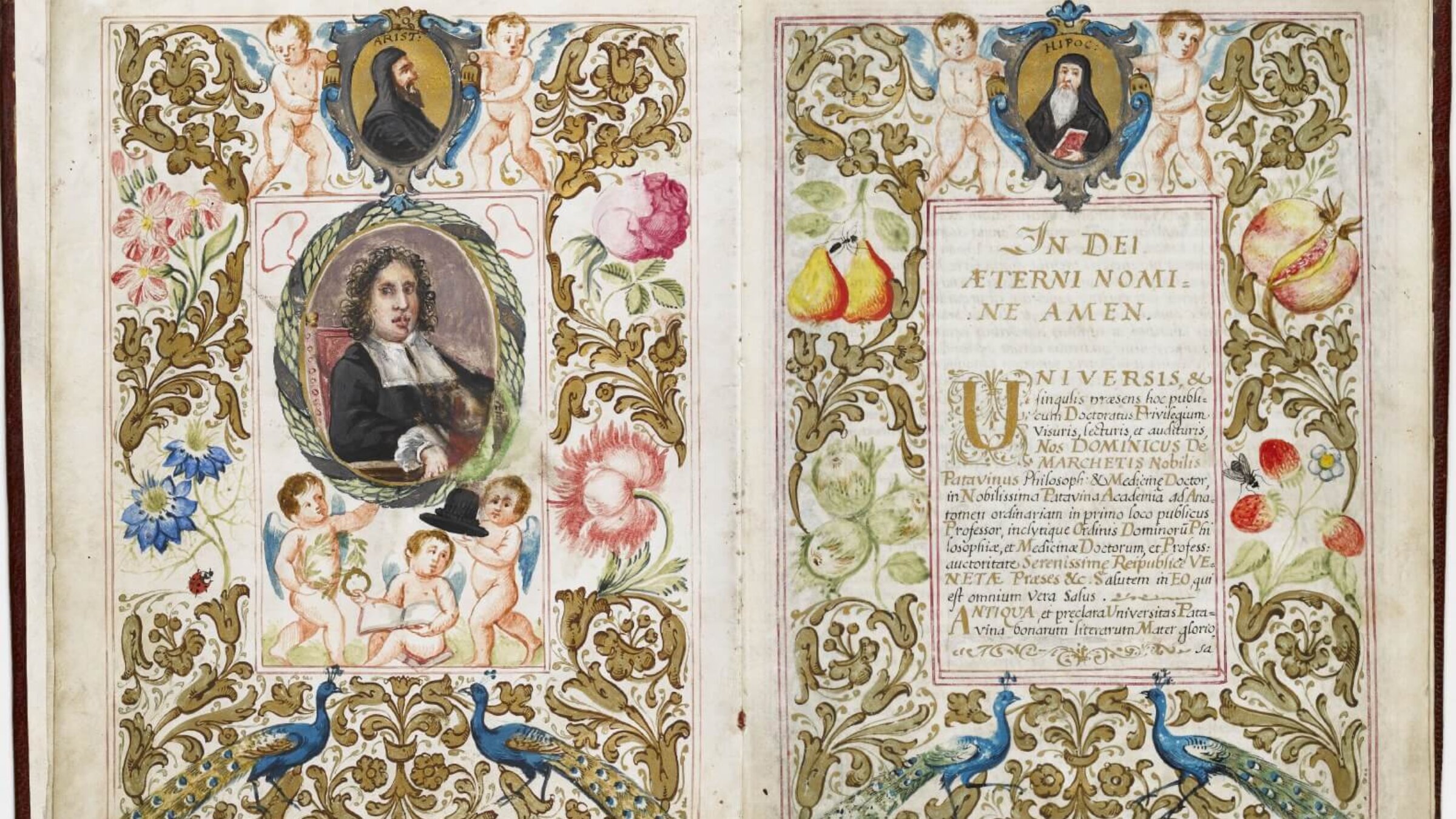

Medical diploma of Moise di Pellegrino (Moshe ben Gershon), Tilche University of Padua, 1687 Courtesy of Gross Family Collection, Tel Aviv, Israel

A new exhibition at the Jewish Heritage Museum of Padua in northern Italy explores a unique aspect of the city’s history: the relationship between the University of Padua and its Jewish medical students during the 16th century. Among the highlights of the exhibition is a rare Yiddish manuscript about the human anatomy.

The Jewish Heritage Museum of Padua is quartered in the city’s Ashkenazi Synagogue, which dates from 1522.

The manuscript is a translation of De Humani Corporis Fabrica (On the Fabric of the Human Body), an anatomy treatise for medical students, written by Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564). Yiddish manuscripts before the year 1600 are rare, and this anatomical treatise in Yiddish is among the rarest of all.

The University of Padua was founded exactly 800 years ago, in 1222. Independent of papal control, it admitted students who were not Catholic and was exceptional in admitting Jewish students. Its highly regarded medical school opened in 1250, and Jewish graduates were among the most distinguished physicians of their day.

This exhibition, which marks the 800th anniversary of the University of Padua and its relationship to Padua’s Jewish community, tells their story. Vesalius was a professor of anatomy at the University of Padua and is considered the founder of modern anatomical science. His famous anatomy treatise, written in Latin, provided anatomical terms in several languages, including Hebrew. Jews played an important role in translating medical works and would certainly have found these translations useful. Vesalius was apparently assisted in preparing the Hebrew translations by a Jewish physician who was also a friend of his.

The Yiddish translation of the treatise was made in Germany between 1590 and 1596. It was most likely made from a pirated 1551 German translation of part of Vesalius’s work in Latin, according to the University of Pennsylvania’s Rare Book & Manuscript Library, which now owns the manuscript. It can be accessed online, too. While Jewish students from German-speaking lands could have read the German translation, those from Poland would have found a Yiddish translation more useful. Quite a few Jewish students from Poland studied medicine at the University of Padua. Some of them were supported to do so by the Polish aristocracy.

Jewish students who arrived in Padua without knowing Latin or Italian faced other challenges as well. Cadavers for dissection were in short supply, and all students were expected to provide them. Jewish medical students protested because desecration of a Jewish corpse is prohibited by Jewish law.

To make matters worse, Jewish corpses were prized because they were fresh, having been buried so quickly. A scene depicting a grave robbery at night and under guard, an indication that the exhumation was sanctioned by the authorities, appears within an elaborate initial letter on a page in De Humani Corporis Fabrica. One small clue, a mysterious “O” on a pennant held by a flying putto (cherub), led Dr. Jeffrey M. Levine, MD, to conclude that this was a Jewish cemetery. He connected that “O” to the “O” of the badge that Jews on the Italian peninsula were supposed to wear on their outer garment to distinguish them from Christians, a law that was not always enforced. He concluded not only that the cemetery was Jewish, but also that the flying putto symbolized a Jew protesting the desecration of a Jewish corpse.

Italy during the 16th century was a center of literary creativity in the Yiddish language, from Arthurian courtly epic to love stories and satire. This rare Yiddish manuscript now took its place among the texts available to Ashkenazi Jews who began settling in Italy during the late Middle Ages or who came to study at the University of Padua.

Rabbi Edward Reichman, professor of emergency medicine at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, who also holds the Rabbi Isaac and Bella Tendler Chair in Jewish Medical Ethics at Yeshiva University, has organized a virtual tour of the fascinating exhibit.. The exhibition at the Jewish Museum of Padua, “Jews, Medicine and the University of Padua,” closes on Dec. 31.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO