When anti-Zionists take over your Hebrew school

What is it about Hebrew school that nobody can seem to get right?

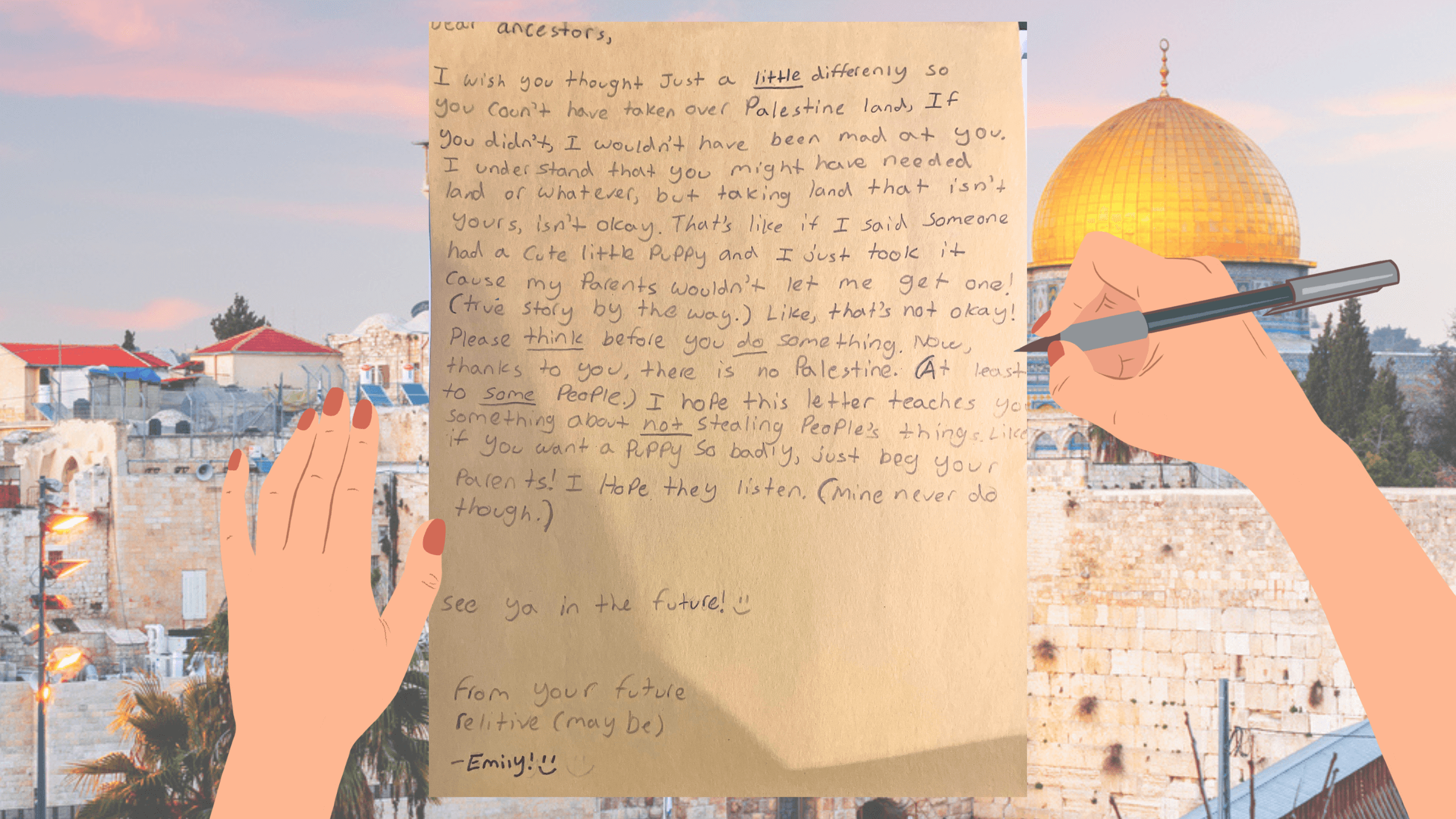

Carolyn Weiss said she snapped a picture of the letter before she asked her daughter about it. Photo-illustration by Odeya Rosenband. Photo by Sean Pavone via iStock and courtesy of Carolyn Weiss

The “Dear ancestors” letter that Carolyn Weiss found in her daughter’s Hebrew school folder had all the hallmarks of a fifth grader’s writing assignment: a few spelling mistakes and misplaced capital letters, exclamation points and smiley faces, plus an allegory about a kid whose parents won’t let her get a puppy.

“I understand that you might have needed land or whatever, but taking land that isn’t yours, isn’t okay,” wrote Emily, who is 10. “That’s like if I said someone had a cute little puppy and I just took it cause my parents wouldn’t let me get one! (true story by the way).

“Please think before you do something. Now, thanks to you, there is no Palestine,” she continued. “I hope this letter teaches you something about not stealing people’s things. Like if you want a puppy so badly, just beg your parents! I hope they listen. (Mine never do though.)”

When Weiss asked her daughter about the letter, Emily burst into tears and ripped it up. To Weiss — who was bat mitzvahed in Israel and has siblings-in-law who are Israeli — it was a stark and horrifying example of how the “Open Tent” policy of Kolot Chayeinu, their non-denominational congregation in the People’s Republic of Park Slope, Brooklyn, had, since Oct. 7, been hijacked by anti-Zionists.

“A line was crossed,” she told me when we spoke this week. “Not just the letter, but how she talked about it. ‘Coerce’ is probably too strong a word, but that she was instructed to write it this way. This is a complicated issue, and there’s not really an easy right or wrong here. Do you think you’re going to indoctrinate them into your cause this way?

“What is it about Hebrew school,” she wondered in frustration, ”that nobody can seem to get right?”

The Hebrew school of my childhood was, in a word, boring. We went three days a week, Sunday-Tuesday-Thursday, two hours a shot. I learned a decent amount of Hebrew, a lot about holidays, a little about Jewish history — and resented virtually every minute of it.

For my kids and many of their friends, Hebrew school has been a happy place. They learn a lot less — and go fewer hours — but like it much more. “Positive Jewish experience” is not just the end goal but in many ways the curriculum.

The most recent census by the Jewish Education Project, conducted in 2019-2020, found that 141,000 children attended 1,458 after-school Hebrew schools across the United States and Canada. That was a 40% drop from 13 years before.

Most Hebrew schools across denominations — along with most Jewish day schools and summer camps — have for generations made a grave mistake by peddling a narrow Israel-right-or-wrong message rather than grappling with the complexity around the founding of the Jewish state and its relationship with the Palestinians.

This is a significant factor fueling the rise of anti-Zionism among young Jews who, reasonably, feel betrayed by the reductive oversimplification of their Jewish educations. Given a false binary of supporting Israel “or” Palestine, we should hardly be surprised that many pick the side that seems more aligned with the social-justice values they learned at Hebrew school than the jingoistic flag-waving they saw there.

Kolot Chayeinu’s version of Hebrew school post-Oct. 7 seems like a cartoonish overcorrection. Weiss told me that most of the teachers were wearing “Ceasefire Now!” T-shirts at an open house for parents in December. One Monday in February, she received an email saying that afternoon’s classes were canceled so teachers could attend a pro-Palestinian protest.

And have a look at what the fifth-graders put together around Hanukkah:

I, too, would like to live in a world where there was no war and the movie version of Taylor Swift’s Eras tour streamed for free. Also one in which the Hanukkah wish list at a synagogue Hebrew school would include “free the hostages” along with “end of the occupation.”

Not at Kolot. Weiss shared with me a document compiling the notes sent to fifth-grade families about the classwork. It runs 18 pages but does not include the word “hostages.” There are 36 mentions of “justice,” four of Palestine, two of Gaza.

“Israel” shows up only once, in a paragraph about a screening of the animated short I Am From Palestine: “We provided some historical context about the founding of Israel and took student questions,” the notes say. This was a precursor to the letters-to-our-Zionist-ancestors assignment.

I reached out to Kolot’s Hebrew school director, executive director and clergy, but they declined to talk to me — or answer any of my specific questions, including whether any teachers were disciplined over the letter-writing assignment. They would not even tell me how many students are enrolled in their program.

Instead, Kolot’s president, Anne Sherman, sent an email saying that “this has been an extraordinarily challenging time” and that, “much like other congregations and Jewish institutions, this year especially we are experiencing tensions and concerns about how Israel/Palestine is being addressed.”

“We are a congregation that includes anti-Zionists, non-Zionists, liberal Zionists, and everything in between,” the note said. “We are proud that what we call our ‘Open Tent’ allows us to hold these differences and have these discussions.”

The head of school, Jessica Moore, who had subbed in for the teachers who skipped Hebrew school to protest in February — and then replaced them — wrote a letter of apology about the “ancestors” project in June, after Weiss complained about it. She said she did not know about the assignment; that it was not part of the curriculum; and that “Kolot in no way condoned” it.

“I am saddened to hear that students had this experience at Kolot, and deeply concerned to know that this happened without approval from me, senior staff, or clergy,” Moore wrote. “We are confident that the new teaching staff I hired shares our belief in the importance of intellectual autonomy and safety of students.”

Kolot is certainly an outlier among the nation’s synagogues and Hebrew schools, and even in the proudly progressive precincts of brownstone Brooklyn. In most communities, the struggle is over how to ensure the Palestinian narrative is given a fair airing, how to present a nuanced picture of the conflict, how to build in Jewish kids both a connection to or love for Israel and the ability to see its flaws.

That is, after all, how we teach our kids about America.

David Bryfman, head of the Jewish Education Project, told me that after years of discussion about the need to revamp Israel curriculum, Oct. 7 “was a bit of a wake-up call for people to start teaching with nuance.”

“They’re all desperately trying to up their game by recognizing that what they said before is not good enough for now,” Bryfman said. “They know they’ve got a lot of fixing to do with the curriculum. They know they can’t avoid the Palestinian narrative. This is from Modern Orthodox day schools to socialist camps, we’re seeing it across the board.”

What feels so surprising — and troubling — about Weiss’ experience at Kolot is that it was the kind of hegemonic anti-Zionism that Jews who live in places like Park Slope (or my New Jersey town, the People’s Republic of Montclair) have been facing in secular spaces, and especially in leftist activist movements. Many increasingly see synagogues as the only safe places to talk about Israel (and Palestine), places where their concerns and confusions will be understood.

They should not be the only such places. But they must be such places. Kolot was not such a place for Weiss and her family.

When Emily’s teachers told her to write a letter chastising her ancestors for stealing Palestinian land, they may not have realized the implications. As it turns out, Emily’s father’s grandparents survived the Holocaust in Warsaw, Poland — one passed as a Pole and the other was hidden at a farm — and emigrated to Israel in the year of its founding, 1948. Emily’s grandmother, Shoshana, was born there two years later.

I don’t know why Emily signed her letter “Your future relitive (maybe).” But it’s revealing, and true. If her great-grandparents had not moved to Israel — had not “taken over Palestine land,” as Emily was told to write in the letter — maybe Emily would not even exist.

Next year, Emily and her younger sister, Sylvie, will be going to a new Hebrew school called Fig Tree, which is not associated with a synagogue, and will have about 400 students in various locations in Brooklyn, Queens and Manhattan. Rachel Weinstein-White, who created Fig Tree a decade ago, told me her curriculum and pedagogy is decidedly “not Israel-focused” and that the program has mostly Israeli teachers, many Israeli families, but also “pro-Palestinian teachers and families.”

“The primary message has been, ‘We’re all Jews, we can have hard conversations and we will,” she said. “We’re about teaching children to love Judaism. And if they love Judaism, they’ll be Jewish adults, and as Jewish adults they can make their own decisions about Israel.”

And then, if they want, they can write letters to their ancestors about it. Or they can just get their kids a puppy.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO