Students retake encampment at MIT, where protests take on a mathematical spin

At one the world’s greatest centers for science, protesters draw on math theory and a pro-Israel engineering student invokes her Muslim father

Photo-illustration by Odeya Rosenband. Images by Steve Marantz and Mel Musto/Bloomberg via Getty Images

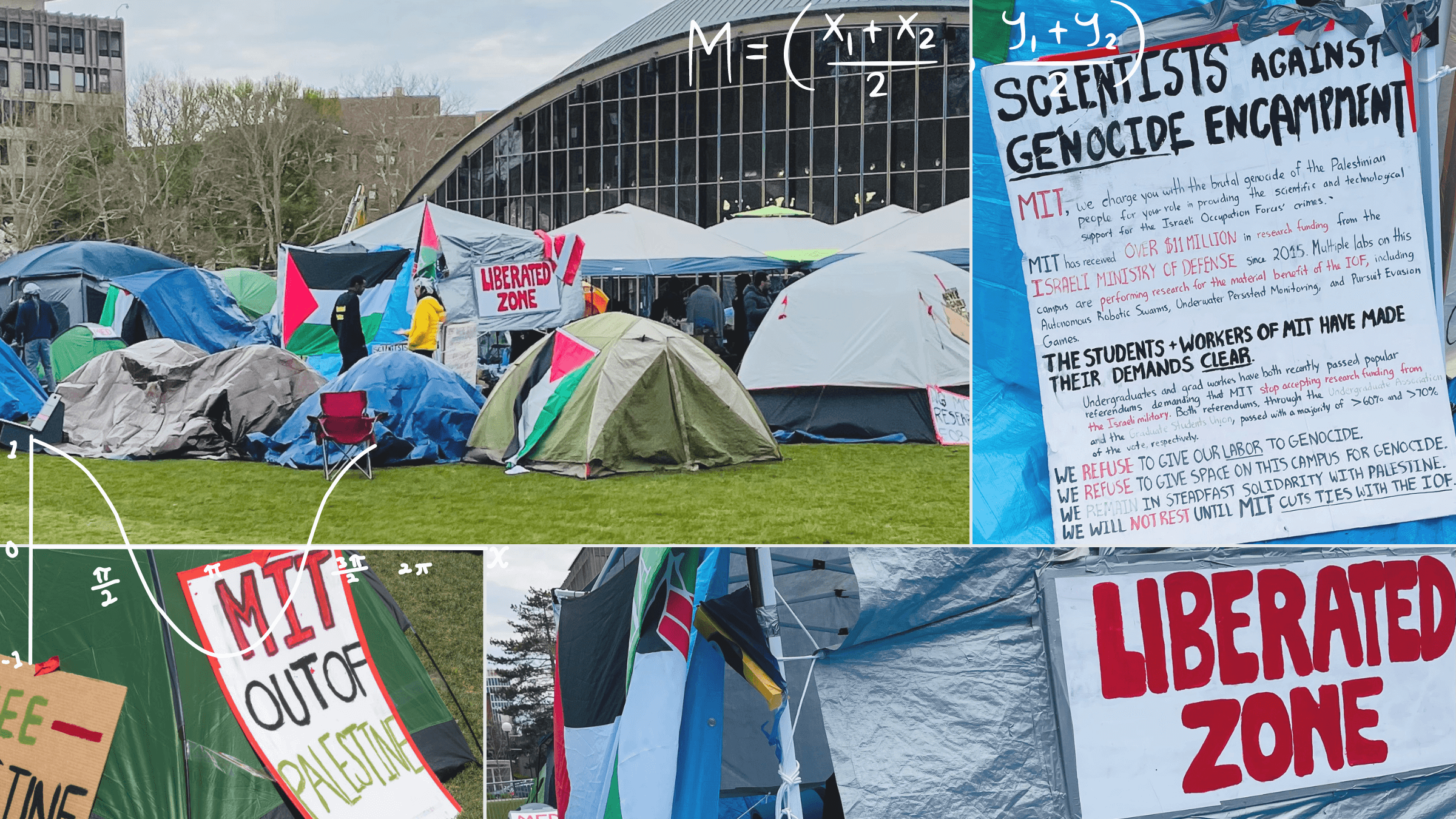

Pro-Palestinian protesters Monday night retook an encampment that had been mostly emptied that day after administrators at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology brokered an agreement with students.

A handful of protesters had refused to comply with a deadline to vacate the area or face suspension. But when most of the encampment had been cleared in the late afternoon, one protester jumped a barrier surrounding it, and was followed by scores of others. Police have not yet reported any arrests.

The retaking of the encampment makes MIT unusual among the dozens of colleges where students have erected them in the past three weeks to demand schools divest from Israel. More commonly, universities have dismantled encampments — forcibly or after negotiating with students — or let them stay.

The protest movement at MIT also stands out in the way it connects to the character of the university, one of the world’s most famed centers for math and science research. Protesters focus on the university’s contracts with the Israel government, and argue that the fruits of MIT’s laboratories should not benefit Israel’s military.

I recently spent several days at MIT, interviewing students, faculty and campus rabbis. Here are the stories of, among others, a protester who debates with math, a pro-Israel engineering student with a Muslim father, and a rabbi who wonders why protesters were permitted to pitch tents where a menorah was not allowed.

Mathematical proof

One contentious chapter of the protest at MIT revolved around the applied theory of 19th-century German mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss. And if you haven’t heard of him, you probably don’t have an MIT degree. (Unlike Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who has two.)

Pro-Palestinian students attended a faculty meeting in February, and under the rules could observe but not speak. A tenured professor, noting that pro-Palestinian protesters had videotaped past meetings and leaked them to the media, moved that the meeting go into executive session, which would require all non-faculty to leave. Professor Peko Hosoi, who chaired the meeting, called for a vote of faculty in favor of the motion, and declared that it passed, without calling for votes against. The students were summarily ejected.

One of the students ejected was Prahlad Iyengar, a graduate student in electrical engineering. “There was a lot of feeling that this was done in an unfair way,” Iyengar recalled.

Hosoi, who teaches mechanical engineering, came to second-guess herself. She published a “mea culpa” in the faculty newsletter that included a defense of her decision not to call for the no votes — and grounded it in Gaussian theory.

She reasoned that because the total number of faculty at the meeting was consistent with prior meetings, she could use Gaussian theory to estimate the no vote. “In that case,” she wrote, “the expected number of no votes would be: # no votes = mean(# total votes) – # yes votes = 69.5 – 42 = 27.5 which would not have been sufficient to overturn the yes vote.”

But Iyengar wasn’t buying it. He published a response in the April faculty newsletter titled: “Questioning the Mea Culpa: Mathematically and Administratively.”

“The analysis is faulty on three levels,” he wrote. “This abuse of the Gaussian betrays at worst a deliberate manipulation of the reader, and at best a confusion of the role of Gaussian distributions in statistics.”

Iyengar’s letter went on to suggest that Hosoi’s errant math reflected a larger “structural problem” with how MIT has disciplined and deprioritized pro-Palestinian students.

He cited revocation of an Instagram page where student groups advertise themselves, threatening student protestors with suspension during a November sit-in, and issuance of a non-contact order with the MIT office that deals with racial bias and harassment. He wrote that “Jews for Ceasefire has consistently faced administrative barriers which devalue their anti-Zionist Jewish perspective.”

Sunning himself in a lawn chair at the pro-Palestinian encampment on MIT’s Kresge Lawn, Iyengar told me of an informal lunch where he presented Hosoi with a draft of his critique.

“She said I should flesh it out and we can have a discussion,” he said. “I don’t imagine that she hates it, but we haven’t had a real conversation about it. She’s math faculty so she’s not going to discourage a student from doing math.”

‘My father does not want to wage jihad’

Talia Khan, the charismatic president of Chabad at MIT and co-president and founder of the MIT Israel Alliance, does not spell her last name the way Jewish people usually do — “Kahn.” That’s because her father is Muslim.

A 26-year-old grad student in mechanical engineering, Khan speaks for many Jewish and Israeli students on campus who think MIT has been tolerant of protesters. She testified before a congressional roundtable, appears throughout media, and doesn’t hesitate to lead her followers into the pro-Palestinian Kresge Lawn encampment.

She posted to social media last month about bringing fresh Israeli watermelon to the encampment and singing songs of peace with other pro-Israel students. “We came as a group and stayed together. We were scared for sure, but we will continue spreading Jewish joy even though it’s scary.”

Despite the joy, she accuses MIT of abetting what she calls months of hostility, threats and fear experienced by Jews on campus. She rebukes MIT President Sally Kornbluth for allowing the encampment to persist despite university rules that disallow it.

“We’re really fed up with these people acting with impunity, and emboldened to continue breaking rules, to make our lives more hellish,” said Khan, who has been studying at MIT for more than eight years.

She said she knows Jewish students who decided to take the semester off to avoid the hostility, and that “MIT is watching as Jewish students decide not to come back here next year,” she said. “It doesn’t care about the Jewish brain drain.”

Kornbluth, in her testimony before Congress and in numerous emails to MIT students and faculty, has expressed the school’s commitment to combating antisemitism. She is also Jewish, raised in a Jewish home in Paterson, New Jersey.

Khan was raised in a Jewish home in Phoenix, the daughter of an Afghan father and Jewish mother.

“I was raised Reform, went to a Reform Jewish day school, and a Catholic high school,” she said. “When I got to MIT, I got more involved with Chabad. I think now I would consider myself Modern Orthodox.”

Having a Muslim father, she said, may foster her empathy for Muslims, and it “certainly allows me to clearly fight back from people who say that I am Islamophobic, which is obviously not true.”

She objects when people describe the conflict in the Middle East as a fight between Jews and Muslims. “The vast majority of normal Muslims don’t support Hamas and other terrorist organizations,” she said. “Certainly my father does not want to wage jihad; he married a Jewish woman.”

The personal cost of her activism, she said, is less time to prepare for her qualifying exam for a doctoral program at MIT. She has already postponed the exam once. You get two opportunities to pass.

“This is why I’m furious,” she said. “I’m still talking to reporters when I should be studying, so that we can spread the word on what’s happening here and keep the pressure on MIT.”

Jews at the sit-in

MIT has about 250 Jewish undergrads and 420 Jewish post-grads, comprising about 6% of its 11,920 students.

About 50 Jewish students align with Jews for Ceasefire, a group that professes anti-Zionism, which it likens to white supremacy, and solidarity with Palestinian liberation, which, it says, will bring about the end of “Israeli genocide, apartheid, and occupation.”

Two members of Jews for Ceasefire, part of the encampment at Kresge Lawn, invited me to talk with them.

Both took part in a Coalition Against Apartheid sit-in on Nov. 9 in MIT’s main lobby. Both say their Jewish upbringings led them to join the movement for Palestinian liberation.

“I was raised on the story that Jews in my family were part of the civil rights struggle, that solidarity between Jewish Americans and Black Americans was a natural tie, ” said David Berkinsky, 27, a grad student in chemistry from Mendham, New Jersey.

“It’s a very natural transition from this American-centric view of Jewish-Black solidarity to Jewish solidarity with all oppressed people in the world, which includes Palestinians.”

His companion gave only her first name, Asya, for fear of retribution. She is 35, a grad student in urban planning, and a Russian-born Jew who lived in Israel before her family settled in Silicon Valley.

“As a child in Israel we were afraid of this nebulous circle of enemies surrounding us, so there was this constant fear that at any time someone will take it all away from you,” Asya said. “But when I moved here I walked away from all that. It doesn’t make any sense that you need to deeply oppress a people and that’s the only way you can survive.”

During November’s sit-in, when pro-Israel activists arrived, several targeted Jews, Berkinsky said.

“They really took exception to us being there and let us know that we were not real Jews, that we were fake Jews,” he said. “One person said, ‘God made a mistake having you be born a Jew.'”

After the sit-in Berkinsky, Asya and other like-minded Jews formed Jews for Ceasefire. “We realized there was a void in the Jewish community for folks like us who are Jewish, and are not fake Jews, and wanted to embrace our Judaism while at the same time saying what is happening in Gaza is absolutely horrible, that it’s genocidal, and it sickens us to feel like this genocide is done in our name,” Berkinsky said.

Both he and Asya declined to comment when asked their views on Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack, and other terrorism against Jews. Their immediate focus is on the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement, they said, and referred to Israel’s financial support for research at MIT.

“This is one way MIT is different,” said Asya. “A lot of universities are invested in mutual funds, so it’s difficult to figure out where the money goes. We have a unique position at MIT, this direct relationship with the Israeli Ministry of Defense.”

While protesters at other universities have pitched “Gaza solidarity encampments,” MIT has its “Scientists Against Genocide Encampment,” the aim of which, according to its website, is to “end all research contracts sponsored by the Ministry of Defense of Israel.”

Since 2015, the group claims, MIT has received over $11 million in authorized research funding from Israel’s Ministry of Defense, with $4 million of the total spent. MIT did not immediately respond to a request for comment on those figures.

“There’s no moral ambiguity here,” said Berkinsky. “We know we can push for this and fight for a better MIT.”

Frustrated rabbi

Avi Balsam would have liked to have gone to MIT’s Hillel for Passover, where he is its vice president of programming. The 21-year-old sophomore went home to New Jersey instead. (Note: Balsam is on a Forward advisory board made up of college students from around the nation.)

He told me he felt uncomfortable walking past the encampment, wearing a kippah, to get to the Hillel building. “I didn’t feel it wise, as a visibly Jewish student who cannot hide his Jewishness, to be on campus at this moment,” Balsam said.

He shares the frustration of many Jewish students with MIT’s administration and wrote about it for the student newspaper. It’s mitigated, he says, by the unity and purpose of Jews on campus in the aftermath of Oct. 7, notwithstanding Jews for Ceasefire.

“Many people who would not have affiliated with the Jewish community before have come into the fold and are reconnecting with their Jewish identity, with Israel and Zionism,” he said. “It’s something beautiful I didn’t expect to see.”

Rabbi Menachem Altein isn’t so sure. For the last 10 years Altein has run Chabad at MIT, along with his wife, Mussy, about a half-mile off campus. He estimates that 40-50 Jewish undergrads are regulars at Chabad. Another 100 come infrequently.

“I’ve seen quite a few Jewish and Israeli students who just wanted to show up at class, or at lab, and do some work, and were ostracized for being Jewish and Israeli, like social pariahs,” said Altein. “Then some American Jewish students not involved in Jewish life tell you it hasn’t been that bad,” he continued. “If you put your head down, don’t let your Jewishness show too proud or too loud, bury it away, then everything’s OK.”

Chabad, he said, is where Jews on campus can relax, because Kornbluth and others haven’t stood up for them.

He echoes Balsam’s discouragement with Kornbluth’s handling of post-Oct. 7 tensions, but also recalls a Hanukkah menorah lighting on Kresge Lawn in December, an annual event, as indicative of how the school regards its Jewish students.

The menorah was in a darkened corner of the lawn, he said, so one night Chabad moved it to a better-lit area where the group gathered could sing Hanukkah songs and eat latkes — but the administration came out and ordered them to move it, he said. It was fine with him, he explained, as long as no one else could use the forbidden space.

But then, months later, pro-Palestinian protesters began pitching their tents on the same lawn. “Why not enforce the same rules you enforced on Jewish and Israeli students? Where is the consistency?” he asked.

Altein and I spoke before Kornbluth on Monday gave the protesters a deadline to leave the lawn.

Along with most everybody, the rabbi is bracing for commencement, to be held May 29-31. Several universities, including Columbia and the University of Southern California, have canceled their main graduations for fear of disruptions from protesters.

“They couldn’t shut down an encampment when it was just a few tents,” Altein said. “Am I supposed to think they could prevent something at commencement on a much larger scale?”

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO