Clarence Thomas’ close friend Harlan Crow collects Nazi artifacts. The reason why could be even darker than it seems

The justice’s friendship with the billionaire Republican donor raises ethical questions about Nazi memorabilia

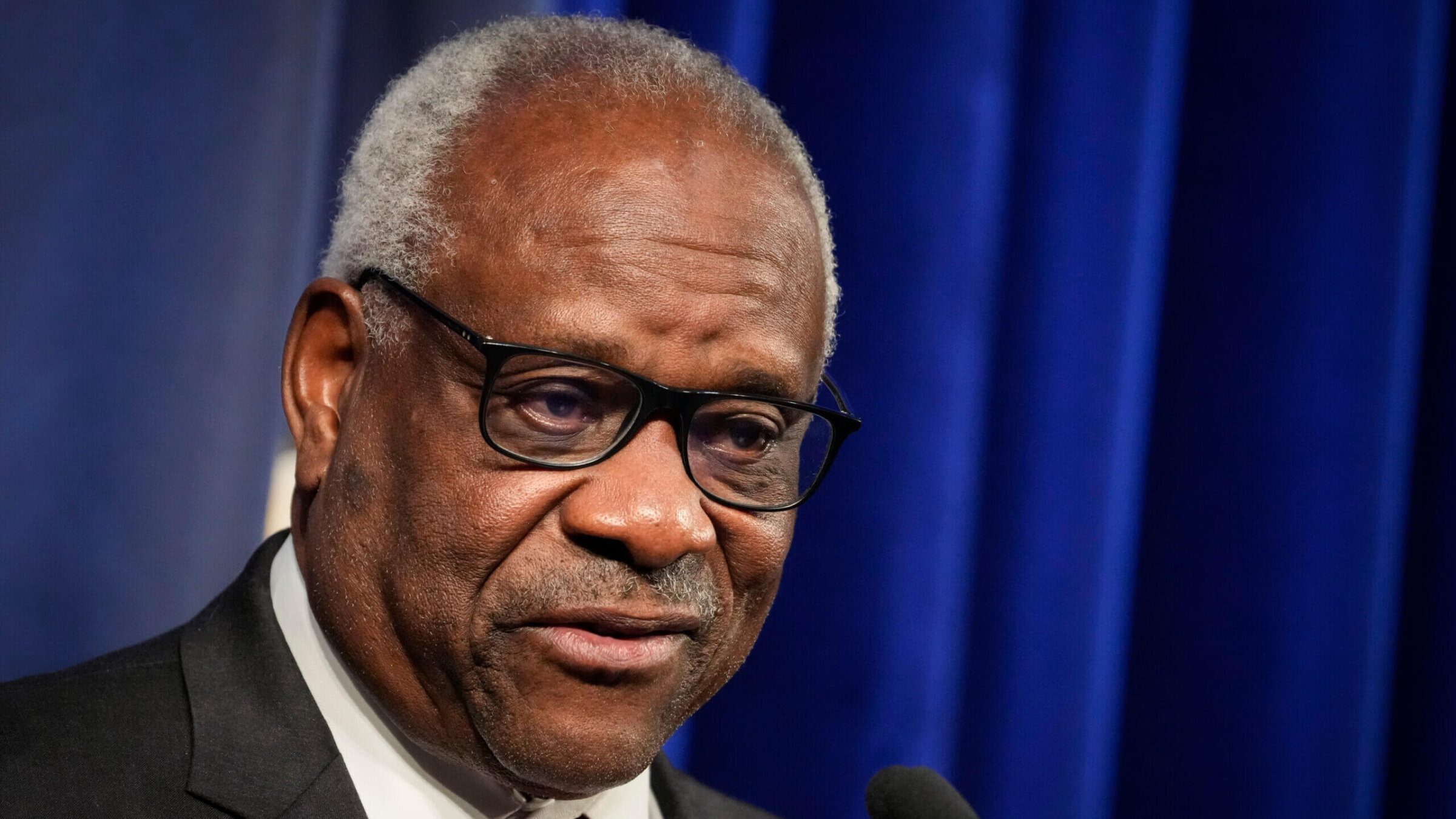

Associate Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas speaks at the Heritage Foundation on October 21, 2021, in Washington, D.C. Justice Thomas’ friendship with billionaire Republican donor Harlan Crow, collector of Nazi artifacts, has recently come under scrutiny. Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images

Billionaire Republican donor Harlan Crow owns a sweeping collection of art and historical artifacts. In his estate in Dallas, Texas, Crow displays rare documents signed by historical figures including Christopher Columbus and George Washington, and original paintings by Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Claude Monet.

He also has a collection of Nazi memorabilia, including two paintings by Adolf Hitler and a signed copy of Mein Kampf, as well as a garden (the “Garden of Evil”) filled with sculptures of dictators, including Joseph Stalin, Vladimir Lenin and Josip Broz Tito.

The consumption of Nazi materials and aesthetics by members of the general public is not new. The term “Nazi chic” has even earned its own Wikipedia page. These disturbing forays into the human psyche may now have resounding political implications, after ProPublica’s reporting that Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas accepted hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of gifts and luxury travel from Crow.

According to Crow, he collects these items because “he hates Communism and fascism.” However, Crow is not displaying these items in the thoughtfully curated setting of a Holocaust museum. Instead, Crow is amplifying the resonance of objects closely associated with evil and antisemitism.

The revelation that a GOP megadonor and friend of one of the most influential jurists in the world collects such unsavory items has caused a dramatic public response. Some conservatives, including some Jews, were quick to defend Crow, claiming that accumulating objects from oppressive regimes can somehow memorialize their victims. Political commentator Ben Shapiro defended Crow by saying his desire to possess these objects is an effort “to remember the things that you hate.” Jonah Goldberg, the editor-in-chief of The Dispatch, tweeted, “It’s not a tribute to evil or something to be mocked. It’s an attempt [to] commemorate the horrors of the 20th century in the spirit of ‘never again.’”

To claim that the purchase and display of paintings by Hitler demonstrates a commitment to genocide prevention and constitutes a memorial to the Shoah takes a great deal of chutzpah. Goldberg’s use of the word “commemorate” is telling. Commemoration can connote celebration, whereas memorialization is more solemn and sincere. If this statement is true and Harlan Crow is actually attempting to honor victims of genocide through his collection of Nazi memorabilia, he is doing a very bad job.

Crow’s 25-year-long relationship with Justice Thomas (noticeably shorter than Thomas’ tenure on the Court) and Thomas’ failure to disclose his receipt of gifts from Crow raises concerns about Crow’s influence on the Supreme Court. In just the past election cycle, Crow donated millions of dollars to Republican candidates and PACs and to several conservative Democrats.

Coupled with the secretive nature of the Supreme Court, Crow’s dark money donations (he once said, “I don’t disclose what I’m not required to disclose”) and Crow and Thomas’ joint visits to an “an all-male club for the rich and powerful” paint a picture almost as ominous as the sculptures of dictators in Crow’s garden — a landscape of secrecy, corruption and a lust for power.

I’m going to say something that will unsettle people, but I’m willing to bet all the money I don’t have that it’s true:

— Leah McElrath (@leahmcelrath) April 9, 2023

Despite how disturbing the materials are Harlan Crow has displayed, there are almost certainly more disturbing items NOT displayed.

The displays are a test.

Whatever one thinks of Crow’s politics, the fact that he actively invites relics of such abhorrence into his home and displays them with pride indicates a bizarrely simultaneous disconnect with the legacy of the Holocaust and also a deep fascination with its horrors, almost to the point of reverence.

If not overtly espousing Nazism, collectors of such artifacts seem to have a perverse fascination with (or ambivalence to) human suffering. Crow’s amassment of statues of brutal dictators may speak to both his fascination with suffering and with cults of personality. His collection also reportedly includes paintings by Winston Churchill and former President George W. Bush. Because Churchill was a moral and tactical enemy of Hitler’s, with Bush falling somewhere between the two on an ethical spectrum, it’s likely that Crow’s attraction to art by all three stems from the paintings’ proximity to political power and global influence, not any aesthetic appreciation.

Regardless of intention, every Hitler-related object, document, and artwork is imbued with his legacy. Every object of such nature is a trophy, a souvenir, an embodiment of the worst of humanity. Crow admits as much of his “historical nod to the facts of man’s inhumanity to man.” Crow also owns items relating to the 1939 sinking of the British ship SS Athenia by a Nazi U-boat, an event his mother survived.

In the final days of World War II, many Allied troops took Nazi flags, knives, handguns, propaganda, and more as trophies — not of the Holocaust, but of fascism’s (ostensible) defeat. It’s not unheard of for people to purchase Nazi artifacts with the intent to destroy them. One ethics columnist suggested burying a Nazi relic and dismissed the idea of donating it to a museum, writing, “Even if you gave it to a responsible museum, it can’t stop people coming in to look at it for the wrong reasons. And again, the museum could always decide to sell the buckle later.”

I believe these items do belong in museums, not in ashes or in the ground. Crow was on to something when he said the purpose of his collection is “to tickle the brain to know more.” Objects, however unpleasant, can be useful tools in education — just not in the setting of a private home.

Crow owns Hitler paintings for the same reason he owns Monets and Renoirs; he owns a signed copy of Mein Kampf for the same reason he owns a book signed by Churchill. These items are status symbols which to Crow, on an unconscious level, grant legitimacy and purpose to his otherwise unconscionable existence of wealth accumulation and political powerbroking. Where the Hitler artifacts stand apart, however, is that Crow, both as a businessman and a collector, is seemingly neither able to distinguish between good and bad, nor has the dignity to exclude the latter from his private collection.

The ancient Greek cynic Diogenes once quipped: “In a rich man’s house there is nowhere to spit but his face.” In Crow’s house, his Nazi artifacts prove to be notable exceptions.

To contact the author, email opinion@forward.com.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO