Pretending to be a gay Haredi man on TikTok does not help queer Orthodox Jews

Changing hearts and minds requires honest portrayals of Orthodox LGBTQ+ realities

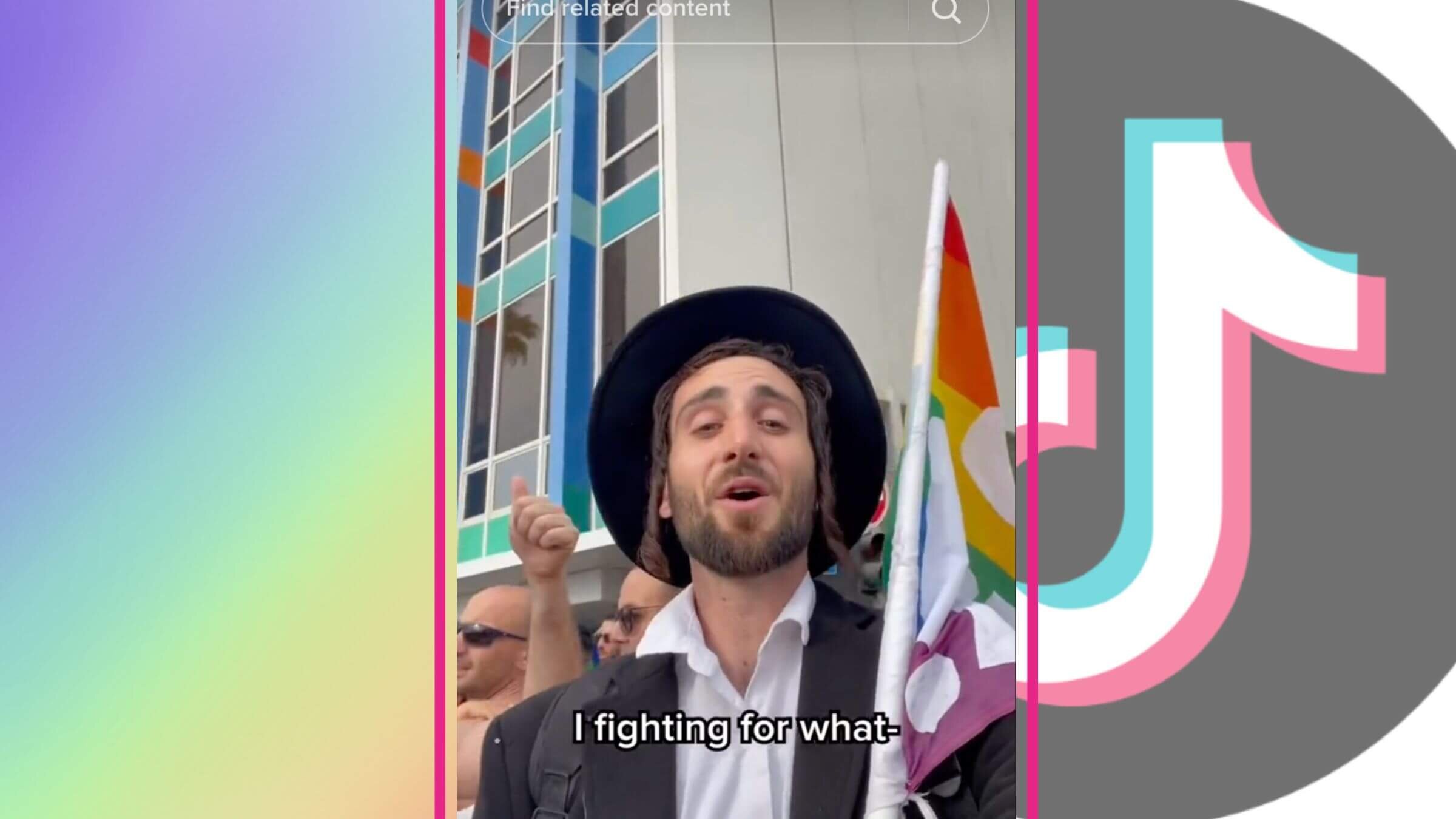

Erez Oved, a secular Israeli, pretended to be a gay Haredi man called Yaacov Levi on TikTok. Photo-illustration by Nora Berman; Screenshot via TikTok/@this.is.kosher

The revelation that popular TikToker Yaakov Levi was not actually a Haredi gay man has rocked the Jewish internet.

Those jarring images of a peot-adorned Orthodox man at the Tel Aviv Pride Parade? The accepting Haredi mother? All fake.

It is not clear whether the secular gay Israeli actor Erez Oved, who ran the account, deliberately led his followers to believe that he was actually a Haredi man. In hindsight, he left enough clues for his followers to be in on the joke. Tasked with taking a deep dive into the account, my 22-year-old daughter who is not even Orthodox returned a verdict within minutes: Yaakov’s Haredi shtick was utterly unconvincing (his sister’s suggestive dancing was one dead giveaway; so is the fact that he never actually talks about his religious identity and experience).

Oved claims that he did not mean to deceive or harm anyone and that he did not pursue the project for fame, glory or financial gain. He wants overly sensitive American Jews now condemning his Haredi drag to just get over it and see his three-year project for what it is: A one-man campaign of joyous Haredi LGBTQ+ visibility.

So what’s wrong with a gay Jew donning Haredi garb and taking an affirmative stance on LGBTQ+ issues?

I take Oved at his word that the goal was to uplift, not mock, Haredi Jews. Indeed, as I learned in my research for a book about the Proud Religious Community, an Orthodox Jewish LGBTQ+ rights movement in Israel, sustained positive public visibility is the best antidote to LGBTQ+ silencing and vilification, still common in Orthodox circles. (As I was writing this piece, Haredi Orthodox Israeli lawmaker Yitzhak Pindrus said that homosexuality presented a bigger threat to Israel than Hamas).

But by turning a fraught public debate and an often painful personal experience into lighthearted TikToks engineered to go viral, Oved minimized, and potentially jeopardized, the very cause he claimed to hold dear: Educating Orthodox Jewish communities about LGBTQ+ experiences.

Acceptance is still a work in progress

While attitudes towards homosexuality are slowly changing in the Orthodox world, the vast majority of Orthodox authorities continue to instruct that homosexuality, including homosexual desire, is forbidden. Even otherwise accepting rabbis discourage outward manifestations of queerness. In the Haredi community, there is little conversation about gender and sexual identities. Religious communities’ silence, invisibility and shame around homosexuality and divergent gender identities is not just stifling, but dangerous. Religious LGBTQ+ persons, including those from Orthodox Jewish backgrounds, are much more vulnerable to suicidal ideation and other mental health challenges.

Changing hearts and minds requires honest portrayals of Orthodox LGBTQ+ realities, in all their complexities. This work, I’ve learned from talking to dozens of Orthodox LGBTQ+ persons in Israel, is difficult, often frustrating, and occasionally dangerous.

Authentic Orthodox LGBTQ+ accounts on social media are now common. The Proud Religious Community organizes entire campaigns around its members’ willingness to share texts and images that proudly feature their faces, names, families and stories. Their yearly Pesach Sheni (second Passover) initiative advocates LGBTQ+ acceptance via a series of community outreach events accompanied by a media blitz of stories about and by Orthodox LGBTQ+ persons.

At other times, private personal moments go public, such as the June 2017 wedding of the Orthodox gay activists Eran and Moshe Argaman. Recognizing that public visibility is both perilous and an opportunity, the public outreach organization Shoval helps Orthodox LGBTQ+ persons narrate their personal stories and provides them with training in public speaking.

Orthodox queer people achieved public recognition through a slow and gradual process of public outreach and education. During their two-decade journey from anonymous chatrooms to being out and proud, Orthodox LGBTQ+ activists have walked a fine line between public visibility and more discreet forms of dialogue.

Throughout the 2010s, it was common for movement organizations to meet discreetly with key rabbinic figures and later post on Facebook a photo featuring activists and their interlocutor, with an accompanying text summarizing the exchange. The posts were sometimes cryptic and divulged few details other than that a meeting had taken place. Activists knew that disclosure of a rabbi’s name or publicity ahead of the event might jeopardize rapport and a still fragile trust.Their patience has helped encourage rabbinic leaders to come out in support for the community.

Public visibility as an Orthodox LGBTQ+ person often comes with a high personal cost. Vilification, name-calling, calls for exclusion and social rejections take a toll of Orthodox LGBTQ+ persons.

Many of my interviewees reported being depressed. Some had experienced suicidal ideation. They frequently spoke of theological angst and mourned the loss of family, friends and communal ties.

Oved’s TikToks make no mention of these personal dramas. His portrayal of carefree and uncomplicated Orthodox LGBTQ+ lives belies the harsh reality that most LGBTQ+ persons from Orthodox backgrounds contend with at one point or another.

But perhaps most disturbing of all is the fact that Levi’s religiosity and sexuality are a shell. Oved’s alter ego may look the part, but does not visibly pray, mention God, engage in Jewish ritual or Torah learning. This makes a mockery not only of Haredi Judaism, but also of the very state of being Orthodox and LGBTQ+. In contrast, authentic portrayals affirm that life is complex by presenting Orthodox LGBTQ+ persons as they are: both observant and queer.

For those interested in learning about this reality, in all its glorious messiness, I recommend Moran Nakar’s docu-series The Holy Closet. It may not be as much fun as watching a dancing, prancing, mocking and playful (purportedly) gay Haredi Jew. But it honestly captures the daily challenges — and joys — of actual Orthodox LGBTQ+ people.

Given the Proud Religious Community’s extensive homegrown activism, queer Orthodox Jews don’t need the help of a performance artist whose work fails to capture, and effectively mocks, the very precarious lives it claims to uplift.

By prioritizing lighthearted fun and sensationalist portrayals over the hard work of winning hearts and minds, the Yaacov Levi account makes a mockery of two decades of activism that have established a durable and authentic Orthodox LGBTQ+ public presence in Jewish life.

To contact the author, email opinion@forward.com.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO