Sigmund Freud understood the uncanny sensation we all felt watching the Trump-Biden debate

In 1919, Freud wrote about how something all too familiar can morph into a shockingly unfamiliar nightmare

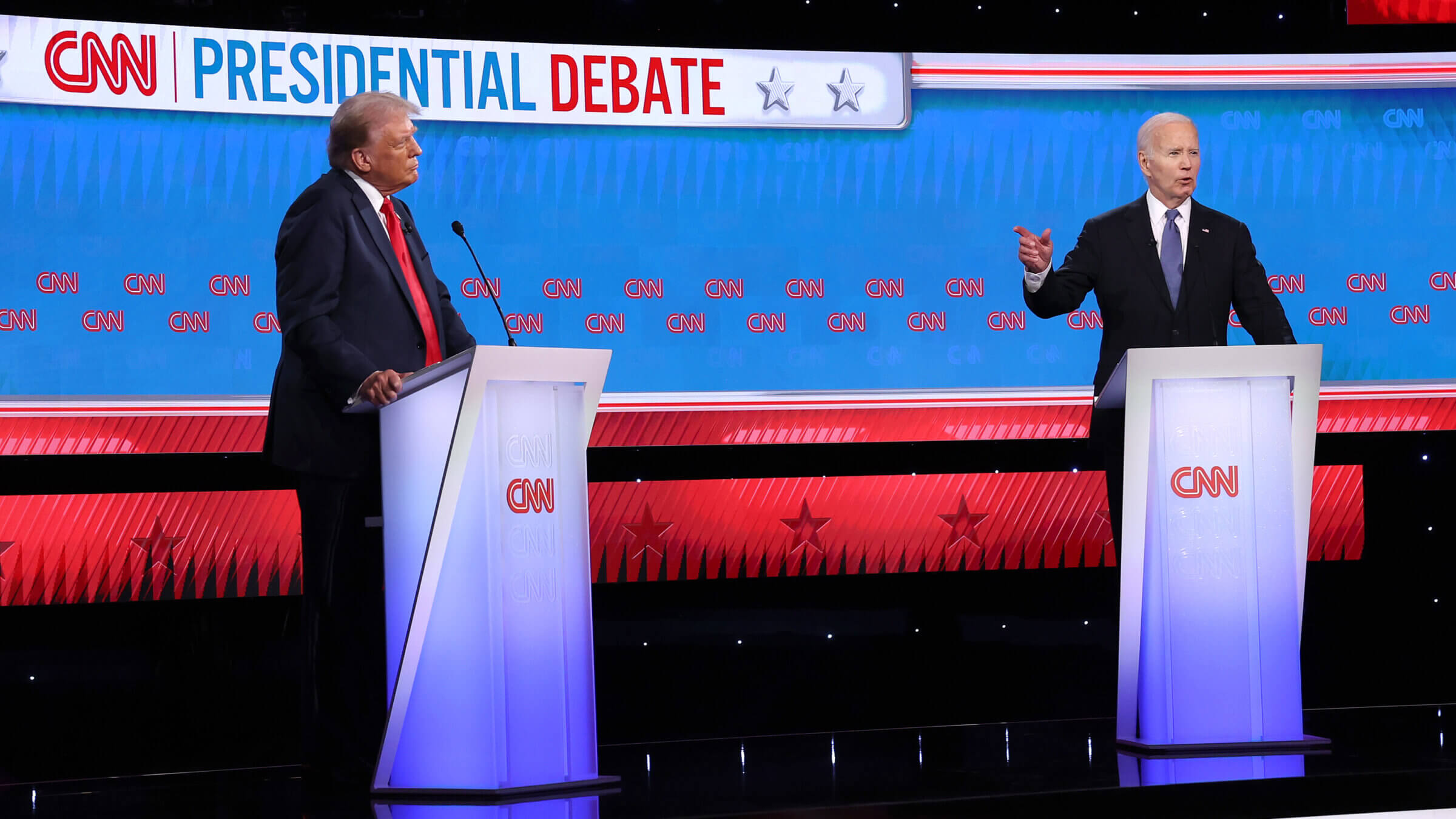

Biden and Trump debaye at the CNN Studios on June 27, 2024. Photo by Getty Images

After last night’s presidential debate, many Americans now feel caught in a nightmare from which they cannot awake. (That many other Americans do not want to wake from this nightmare of course makes all this yet more nightmarish.) It is a nightmare that commentators started to wring their hands over during the debate, twisted more vigorously right after the debate and, as we discovered upon opening our papers and screens this morning, hands they have now mangled into bloody stumps.

We know the reason for this reaction — the future of our imperfect but incomparable democracy was fought over by two elderly men, one ethically impaired and the other cognitively incompetent — just as we know what the commentaries we have yet to read will warn. Just glance at the headlines of the opinion pieces in this morning’s New York Times: “He Must Bow Out of the Race” (Thomas Friedman), “The Best President of My Adult Life Needs to Withdraw” (Paul Krugman), “Biden Can’t Go on Like This” (Frank Bruni), “President Biden, It’s Time to Drop Out” (Nicholas Kristof), and my favorite, “God Help Us” (Michelle Goldberg)

There is no need to add to this chorus, both because these voices carry great weight and because no matter how great their collective weight, it will not weigh enough. How could they when the object of these pleas believes that, despite a “sore throat,” he “did well.” Inevitably, this mix of hubris and blindness in an old man convinced that he alone stands between Donald Trump and the White House, simply compounds our horror.

But there is another and perhaps deeper element to the collective horror now washing over us: the uncanny.

In everyday parlance, the word suggests something or someone beyond the everyday. Instead, it points to a supernatural quality, one beyond what we usually find usual or normal. It is this sense that the word often crops up in accounts of Donald Trump. The once and perhaps future president, according to Fox News, has “an uncanny knack for stealing headlines.” (Fox did not add that he also has an uncanny knack for stealing the money of, say, former students of Trump University.) Or that Trump, as CNN observed, “has an uncanny ability to dodge, or at least delay, accountability.”

But when he coined the term slightly more than a century ago, Sigmund Freud had something slightly different in mind. In 1919, he published an essay titled “The Uncanny,” in which he presents one of the discoveries he made during his journey to the bottom of our psyches. The German word “unheimlich” means something or someone that is unfamiliar or “not from home.” In general, we are scared witless by things so unheimlich or unfamiliar that they are literally alien, like that thing in “The Thing” or that alien — technically, a xenomorph—in Alien.

But, of course, Freud was not thinking of this household variety of the unheimlich. Instead, he turned the word on its head. There are times, he noted, that what is not from home in fact is from home. Hidden or suppressed, it rears up when you least expect it — yes, like the alien bursting through you own chest cavity — and reveals truths you had never considered. The uncanny, Freud asserted, “is in reality nothing new or alien, but something which is familiar and old-established in the mind, and which has become alienated from it only through the process of repression.”

For those who are not Freud-curious, we can tweak his insight to explain last night’s explosion of unheimlich. As my wife Julie and I watched the debate, we felt we were watching a John Carpenter or Ridley Scott flick, desperate to turn it off, but unable to turn away. It was at once both utterly familiar and shockingly unfamiliar, dredging up experiences we have all had but casting them in a new and dark light.

We all have known instances, often within our own families, for example, where a relative, who has spent too much time online, rants and raves at family gatherings. Or at a bar where someone will shout the darndest things before passing out. It is a depressing but not terrifying experience. The familiar remains the familiar, as we mostly just roll our eyes as we look at one another.

It becomes unfamiliar and terrifying, though, when that same relative, or someone like him, sprays verbal sludge across a stage where moderators of the debate refuse to be arbitrators of the truth in front of tens of millions of viewers. More than half of those viewers are thrilled and will vote him into the presidency, while the rest are chilled and paralyzed by horror — including, it seemed, the object of the filth and falsehoods. Rather than roll our eyes, we hide them behind our splayed fingers as we glance at one another. What was once fantastic and the stuff of “reality shows” suddenly becomes real and the stuff of presidential orders and policies.

Yet it is an odd kind of real. In his essay, Freud describes the skill of the horror writer when he “pretends to move in the world of common reality… He takes advantage, as it were, of our supposedly surmounted superstitiousness; he deceives us into thinking that he is giving us the sober truth, and then after all oversteps the bounds of possibility.”

This is where we found ourselves both last night and today. There is no talking cure for this unheimlichian moment — apart, that is, from those he trusts to talk sense to Biden if we are to ever escape.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO