Yiddish film offers authentic recreation of shtetl life before it was destroyed

The title leaves the ‘e’ out of ‘shtetl’ as a symbol of what was lost.

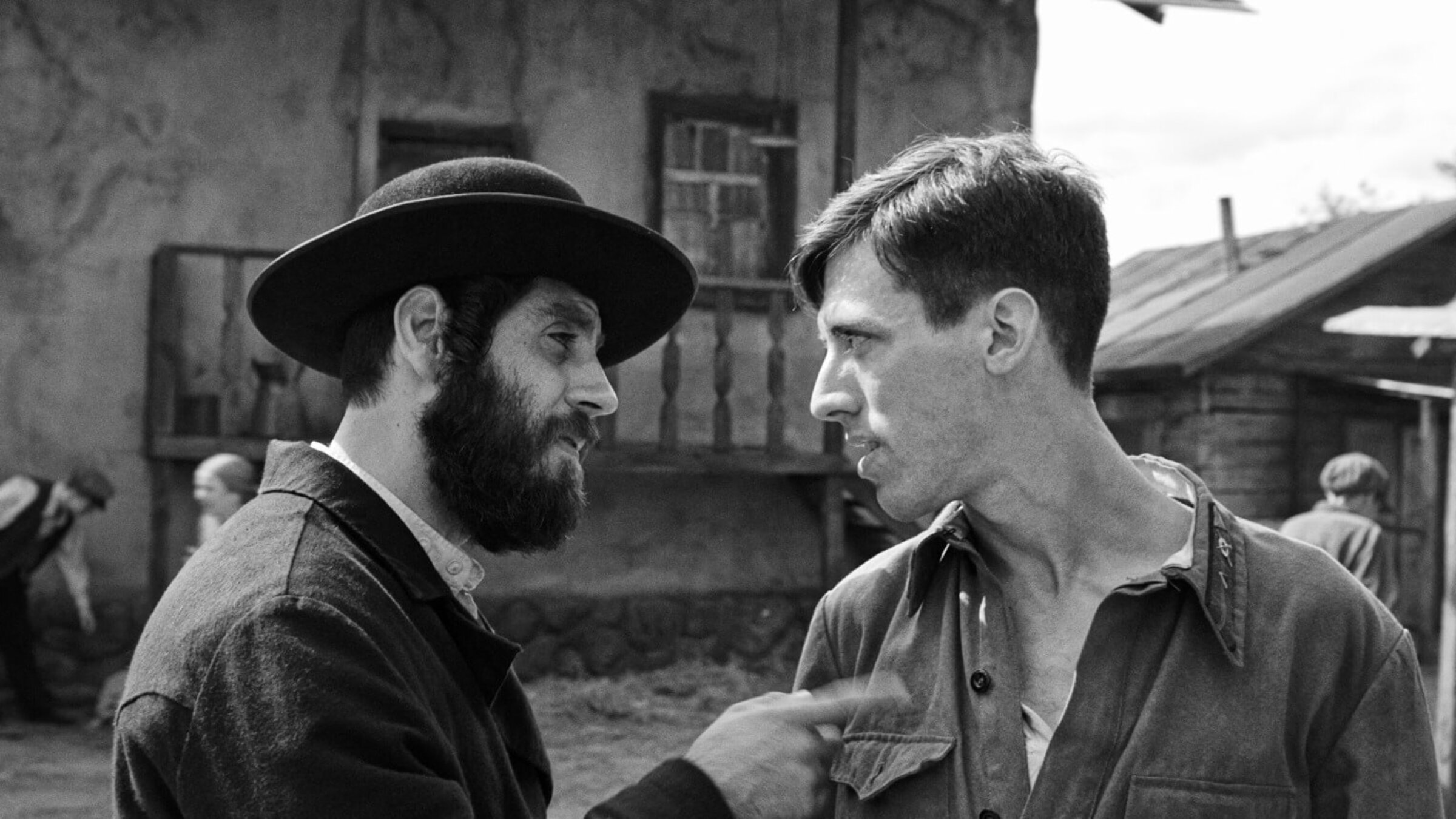

Photo by SHTTL

A new film called SHTTL takes a dramatically different approach to telling the Holocaust story: It depicts the Eastern European Jewish world on the day before it disappeared.

Why did writer-director Ady Walter leave the “e” out of the word “shtetl” in the title? Inspired by an experimental French novel in which that letter never appeared, Walter interpreted this as an absence that left a hollow — an empty space — in much the same way the Nazis did by eradicating the great European Jewish civilization in its midst.

“In order to pay proper respect to the victims, the movie should not only be about death, but more importantly about how they lived,” film producer Jean-Charles Levy said.

The marketplace, shul and houses all seem authentic

Unlike the majority of films about Jewish life of an earlier era, all the dialogue in SHTTL is in the languages that would actually have been used by the characters: Yiddish and Ukrainian. The filmmakers did a stunning job of recreating the shtetl itself. The marketplace, shul and the houses all seem authentic. The actors look like ordinary people, not like actors. And the shtetl community is portrayed not as a cartoonishly monolithic stereotype, but as it really was: riven by factional conflicts between Hasidim, Zionists, socialists, assimilationists and other political movements and trends that were popular at the time.

We’re in an imaginary Galician shtetl. It’s June 22, 1941, two years since the Soviets invaded after signing their pact with the Nazis. Mendele, a young man who left the shtetl two years before to become a film director in Kiev, returns to get his beloved out before she’s married off to an unworthy Hasid. But he remains conflicted: Though his life moved to Kiev, Mendele has left his heart back home.

The larger situation is equally conflicted. While the Soviets in the shtetl work to destroy their Jewish souls, the Nazis wait across the border to implement much darker plans.

Astonishingly, the entire film is done in one single take

Many Yiddish films have been made in the hundred-odd years since the birth of Yiddish cinema, but this is the most ambitious production, utilizing a very broad scope. Instead of filming it as a series of intercut close-ups — the television-influenced style that’s been the norm since the 1960s — Walter wanted something different. Although he had never directed a fiction film before, he decided to use the far more difficult single-shot style in which there’s no cutting at all. It’s all done in a single take. This style, pioneered by Alfred Hitchcock in his psychological crime thriller Rope (1948), has been used often lately, most notably in Sam Mendes’ war film 1917. Its advantage is that the actors always appear much more physically connected to their environment. This serves SHTTL’s purpose perfectly, as the movie is as much about its milieu as it is about its characters.

Walter also uses color conceptually, and to great effect. The movie alternates between black-and-white and color, but instead of the cliched use of color for the present and black-and-white for the past, here it’s the present that’s depicted in black-and-white while Mendele’s memories, with one exception, appear in color. This is Mendele’s story, and the color tells us something about his sympathies, and about how polarized — how black-and-white — his world has become since his childhood.

The performances are, with several minor exceptions, very solid, but the standout is veteran actor Saul Rubinek. Rubinek’s elderly rabbi, though hampered by some anachronistic dialogue, is spot-on. He has just enough authority to serve as the leader of the community, yet also a distinct gentleness that we associate with elderly Hasidic rabbis. Look at how Rubinek uses pauses within his speech when calming an angry crowd. Beautiful.

Despite its authenticity, some moments feel out of place

SHTTL is a remarkable movie. But it’s flawed, too.

The Yiddish, for example, is a mixed bag. Although the dialogue is well written, the actors’ ability to deliver it runs the gamut from authentic Yiddish speech to awkward phonetics. But perhaps that’s nitpicking; had the movie been made in English, it would have felt phony and generic.

A few moments do feel anachronistic, though. There’s an obligatory scene of shtetl feminism that could have been lifted from Barbra Streisand’s Yentl. There’s a discussion of film-as-an-art-form in one scene that feels extremely unlikely for that period. And the idea that the callow Mendele has become a film director in an era when the cheapest movie was still a major commercial undertaking is not at all convincing. Why couldn’t he have gone off to write literature or join the theater, which was much more common for young Jews raised in the shtetl? Also, women are shown attending Friday night services, which is almost unheard of in Hasidic circles both then and now, but was apparently necessary for plot purposes.

Still, what little most Americans know about Jewish life in Eastern Europe comes from Fiddler on the Roof — and even in the moments where it pushes the envelope, SHTTL seems far more authentic than the popular American musical.

The film might also have benefitted from a different opening. There is no real exposition, so we don’t really know who the protagonists are or what they want until later in the film. Instead of getting emotionally drawn into the story, we spend much of the first half-hour trying to figure that out.

The set was supposed to be turned into a museum

That being said, this incredibly impressive production does get so much right. Surprisingly, it was filmed in Ukraine, with a Ukrainian crew, and supported by the Ukrainian State Film Agency, despite Ukraine’s appalling history of antisemitism. But as we know, that’s not the Ukraine of today, which the Pew organization has found to be one of the least antisemitic countries in Europe (and even the least antisemitic in Eastern Europe). After all, a Jewish man won the presidency there in a landslide.

The film was shot 37 miles outside of Kiev. Art director Ivan Levchenko’s superb set — including its beautiful and unique wooden synagogue, which was actually consecrated for use — was to have been converted into a museum commemorating Ukraine’s Jewish past.

Unfortunately, this won’t happen now. The Russian invasion destroyed the shtetl set, the area has seen heavy fighting, and the land has been mined.

But one thing the war can’t destroy is the thousand-year-old Jewish history rooted in the soil of Eastern Europe. By depicting an average day in a Jewish town, SHTTL opens a unique window into that world.

SHTTL will be screened at the New York Jewish Film Festival on Jan. 16 and 17. For more details or to get tickets, go here.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO