‘A Jewish woman, a widow, a damn good painter and a little too independent’ — reclaiming Lee Krasner’s legacy

Freed from the shadow of Krasner’s husband Jackson Pollock, another glorious solo show emerges

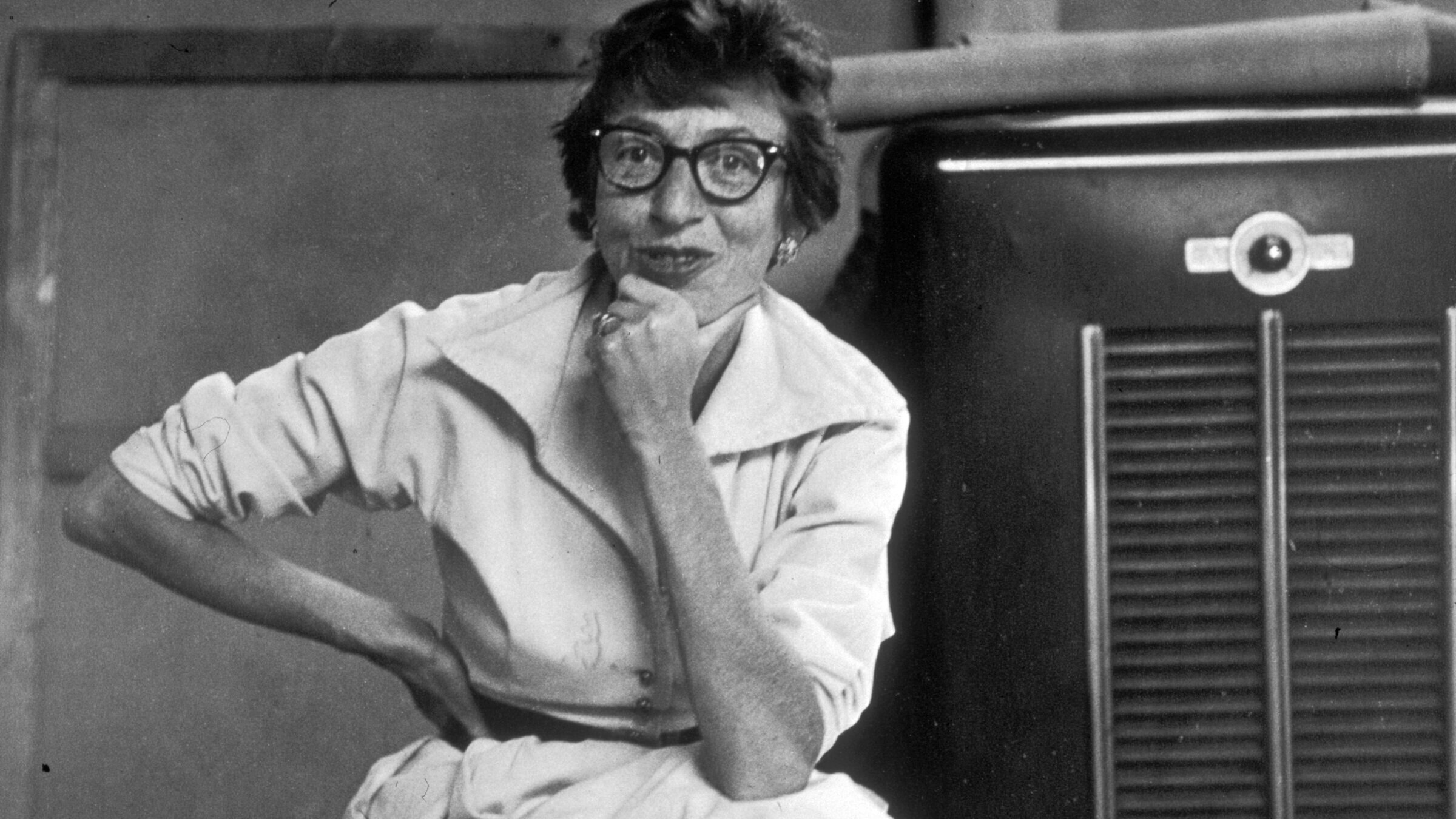

Lee Krasner in East Hampton, 1953. Photo by Getty Images

Before Jackson Pollock became Jackson Pollock, he was Lee Krasner’s husband. Lee Krasner helped Jackson Pollock become Jackson Pollock, until in 1949, Jackson Pollock became God. That made Lee Krasner Mrs. God.

Lee Krasner only ever wanted to be called an artist.

Fast forward to my damp socks, and a quiet, drizzly January afternoon when I was wandering through Chelsea and a sudden downpour led me to seek shelter in Kasmin Gallery where, surrounded by the quiet hum of George Rickey’s kinetic sculptures, I struck up a conversation with the gallery’s front attendant who shared a tip about a forthcoming show. It wasn’t just art but a rediscovered piece of history featuring the reunion of the only two surviving paintings from Lee Krasner’s first solo show.

Krasner, she said, had harbored hopes that her first solo exhibition at the Betty Parsons Gallery in 1951 would echo the fame her husband, Jackson Pollock, had garnered, especially after a 1949 Life article by Robert Coates. Pollock, as anyone who saw the Ed Harris movie knows, was a talented alcoholic and needed someone unflappable to believe in him. It was a lucky match for him. No one then or now would deny that his status was significantly bolstered by his Jewish wife’s networking efforts. Krasner’s solo show in the gallery where he exhibited was one way for Pollock to help pay back some of the artistic debt he owed to his wife.

Krasner, bitterly disappointed by the show’s reception, destroyed or changed most of her artwork during this time, leaving only these two pieces, which marked her shift from figurative to abstract art.

Composing non-compositions

I was that kid who chased extra credit in school, and that evening, at Strand Books, I chanced upon the last available copy of Gail Levin’s 2012 Lee Krasner: A Biography. I emailed Levin, who agreed to meet at her home.

Levin, a very tall and soft-spoken academic, sat down in her living room with me after serving candied ginger and delicate white meringues. Levin told me that she was 21 in 1971 when she first met Krasner; though Levin intended to discuss Jackson Pollock, the conversation with Krasner opened her eyes to women’s challenges in the famously misogynistic world of abstract expressionism. Levin, along with other feminist art scholars, became crucial in redefining Krasner’s legacy, not merely as an artist’s widow but as a trailblazer in her own right. In 1978, as a young co-curator of the Whitney’s “Abstract Expressionism: The Formative Years,” Levin pointed out that Krasner had been doing abstract art even before she met Pollock.

“I happen to be Mrs. Jackson Pollock, and that’s a mouthful,” Krasner told Levin during that first meeting in 1971. “I was a woman, Jewish, a widow, a damn good painter, thank you, and a little too independent.”

“Lee told it like it was and could be pretty grumpy, but who wouldn’t be with rheumatoid arthritis,” Levin told me. “Frankly, she was always in pain. And she got caught up in that 70’s quackery, like those copper bracelets, foolishly thinking they’d help.”

Later that night, I read a short essay by painter Claire Seidl, a current member of American Abstract Artists which Krasner was also a member of. For AAA’s new journal on pioneering artists who inspired members now, Seidl wrote about Krasner’s painting “White Squares,” which was part of the artist’s “Little Image” series from the late 1940s — small, detailed works with abstract patterns that Krasner created by painting on a flat surface for a more careful application.

Seidl explained that this series saw Krasner moving away from traditional composition to a concept she called “non-composition,” spreading the visual interest evenly across the canvas in what’s described as an “allover format.” Pollock, too, famously used an allover approach, by throwing paint. You could say Krasner was “writing” her art, using what the artist called “hieroglyphics” — imagery partly inspired by the Hebrew lettering she had studied in her early years.

She got the bedroom, he got the barn

Lee Krasner was born Lena Krassner in 1908 in Brooklyn’s Brownsville, the daughter of an immigrant fish and produce seller who had escaped the pogroms only to work from dawn to dusk in East New York. Her mother maintained the family’s Jewish traditions and superstitions, and her father captivated her with mystical stories and religious texts, even if she didn’t always agree with the old ways. By age 14, she was studying art at Manhattan’s Washington Irving High School, the only school at the time that offered an art major to women.

Embracing the Jazz Age’s exuberance as a teenager before the 1929 stock market crash, Krasner was a good dancer with a chic bob and attracted many suitors. She felt galvanized by MoMA’s 1929 exhibition that featured modern masters like Cézanne and Van Gogh.

Krasner waitressed and art modeled, until she scored work as a muralist for the Works Progress Administration (WPA) from 1934 until 1945. Around this time, she simplified her surname from “Krassner” to “Krasner” and adopted the more androgynous first name “Lee.” She moved in with handsome Russian émigré painter Igor Pantuhoff, whose wealthy family rejected her because she was a Jew. He was not much kinder, as he was known to have said, “I like being with an ugly woman because it makes me feel more attractive.” (Charmer!)

In 1936, at an Artist Union dance, Krasner encountered Jackson Pollock, who had recently arrived in New York and studied at the Art Students League under Thomas Hart Benton. Their first interaction was marked by a crude pass — “Do you like to f–k?” – a distasteful memory she preferred to leave behind.

Krasner and Pollock’s paths crossed again in 1942, when Krasner, by then a fixture in New York’s art circle, was intrigued to find Pollock’s name in a show she also was appearing in. Discovering they were neighbors, she climbed the stairs to his fifth-floor studio. (Great scene in the movie!) This time, Pollock’s raw talent struck her with undeniable force. Pollock, classified 4-F due to mental health struggles, was a rare sight as a single man not in uniform during the war years. (Available!) From there came a romantic and intellectual partnership. With her deep understanding of modernism, Cubism, and surrealism, Krasner found in Pollock both a muse and a catalyst, one that impacted her work just as her insights influenced his.

In 1943, with art sales slumping, Pollock worked as a janitor and elevator operator at The Museum of Non-Objective Painting, later the Guggenheim, only to be thrown a lifeline by Peggy Guggenheim with a game-changing contract. This deal kick-started a more significant painting career, which led to a breakthrough solo show at her Art of This Century Gallery. By 1945, Pollock and Lee Krasner tied the knot at Marble Collegiate Church (His idea. She still considered herself Jewish.)

To help curb Pollock’s battles with the bottle, they snagged a Hamptons fixer-upper in Springs for $5,000, swapping the hustle of city life for the serenity of Gardiners Bay. This transition into a lifestyle rich with artistic pursuits, the preparation of meals at home, and gardening marked the beginning of a golden age of creativity and intimacy.

Krasner worked in their bedroom to save money because the living space was limited. Eventually Pollock got the barn.

In late 1946, Krasner began work on her “Little Image” paintings.

According to Norman Kleeblatt, the esteemed former chief curator of the Jewish Museum who staged the museum’s 2008 “Action Abstraction,” and co-curated a big 2014 Krasner show, “Krasner applied paint in a grid format, in dabs, or carefully poured during numerous sessions. Within this process, she explored the painterly possibilities between extremes of order and chance, with allusions to both writing and pictographic images.”

Though “Lee Krasner” had become a familiar name in New York’s edgiest art circles, in 1949, Pollock was dubbed “the greatest living painter in the United States” by Life, relegating Krasner, in the eyes of the press, to the role of muse and caregiver.

The 1951 solo show at the Betty Parsons Gallery should have been Krasner’s moment in the spotlight. However, not a single piece sold. Krasner began cutting up or repurposing her paintings; today, only “Number 2, 1951” and “Number 3, 1951,” survive.

In 1952, Pollock leaped to the Sidney Janis Gallery which offered him the exposure and financial stability he craved. But this shift had unforeseen consequences for Krasner who was told by Betty Parsons to follow her husband out the door.

“It took me a year to recover from that shock before I could work again,” she confided to Gail Levin in 1973. “I was kicked out of the gallery because I was Mrs. Jackson Pollock.”

Pollock’s alcohol addiction deepened as did his entanglement with Ruth Kligman, a 25-year-old Jewish artist and art gallery assistant, who had the prowling, glint-in-her-eye quality that made artists wish they could draw her and made non-artists wish they could draw. If Catwoman were Jewish, Ruth Kligman would have played her. “You are so young, your eyes are so warm!” Pollock told her. This affair came to a head when Krasner discovered them together in Pollock’s studio. Seeking a mental break, Krasner took a summer jaunt alone in 1956 to Europe, while Pollock, undeterred by a painting left on her easel with her version of an evil eye, moved Kligman into the home in Springs.

On the evening of Aug. 11, 1956, Krasner’s European escape was cut short by devastating news. After spending the day drinking heavily, Pollock was driving his lover of five months and her visiting friend, Edith Metzger, in a green 1950 Oldsmobile 88 convertible near his Long Island home. A few hundred yards from home, he lost control and struck four trees, causing the car to flip. Kligman survived with a fractured pelvis, but both Metzger and Pollock died.

After Pollock’s death, Krasner transformed his studio into her workspace, now a public historic site. She channeled her energy into painting, and, in 1965, had a solo retrospective at London’s Whitechapel Gallery. She continued her work in Springs for 28 years post-Pollock.

Krasner died at 75 from diverticulitis on June 19, 1984, just six months before her MoMA retrospective, making her the second woman after Georgia O’Keeffe to be honored this way. She is buried next to Jackson Pollock in Green River Cemetery in Springs; keeping with Jewish tradition, many visitors leave small stones atop their graves.

A return to Kasmin

On my next visit to the Kasmin Gallery, I was greeted by 41-year-old Eric Gleason, a senior director of the gallery who developed the show in consultation with the Pollock-Krasner Foundation. He opened a door, and led me into a hidden hive of activity reminiscent of a scene from Willy Wonka’s factory — except, in place of Oompa-Loompas, a team of nearly 40 young professionals were silently at work selling art.

Alone in a chic, glassy conference nook, Gleason dished on the epic year-and-a-half quest to launch this exhibit and how getting museum loans from six big-name institutions was a Herculean task. “That’s when you know it’s major,” he said. With just 13 paintings, Kasmin is spinning an entire saga — it is a well-sized display for a gallery but a tight edit, thanks to the rarity of surviving works from this period.

I asked him if this was his favorite of the four Krasner shows at the gallery he has helped to steer. “Her collage paintings are just some of any artist’s most innovative works of the post-war era, and other shows were just heavy-hitting paintings,” he said. “This is a different beast, a show that will be educational for the art world. We’re shining a light on a barely known or acknowledged series. There’s a thrill that comes with that, too.”

Gleason said he was most shocked by what was found underneath some of the reused canvases, which suggested that, contrary to popular belief, Krasner hadn’t actually stopped painting to support her husband’s career.

“She was reusing some of her own canvases, and the verso’s of the paintings in our exhibition suggest changes to the long-held chronology of the works,” he said. “It’s amazing to think that five formative years in the middle of her career have never been adequately acknowledged, especially 1952 and 1953 when she was thought not to have made any paintings at all. The hope is that this show will more firmly put this period of Krasner’s geometric abstraction on the radar. We have a murderers’ row of Little Image paintings that kick off the show chronologically, and we’ve also reunited the only two surviving paintings from Lee’s first solo exhibition, which was at the Betty Parsons Gallery in 1951. Those two paintings are on our back wall together and represent an historic opportunity for any Krasner lover to be transported back to that formative exhibition. The show ends with two masterpieces entitled ‘Promenade’ and ‘Gothic Frieze’ that suggest where she is going next as a painter.”

An evening in two acts

Rain soaked my third visit to Kasmin, yet Lee Krasner enthusiasts were undeterred. The night unfolded in two acts: an intimate gathering for insiders and scholars, then a public reception.

Claire Seidl, my plus-one, and I were the first in the door. In a still empty room, we marveled at the rarely seen “White Squares” lent by the Whitney Museum. Seidl, who sheepishly admitted that she had written about the piece after only studying it in a photograph, was delighted by its unexpected texture in person. Intrigued by its stretched taffy appearance, I learned from Seidl that Krasner and Pollock blended readily available house paints into their works. It was fun to imagine that the same can of black in “White Squares” may have been used for a Pollock drip.

When the gallery was full with the first lot of guests, I managed to take Gleason aside to congratulate him on the exhibit. I asked when the Lee Krasner exhibition had been ready. “At noon!” he said with a laugh, adding that the last work had arrived by courier only that morning. After everything was installed, he said, he had walked around the exhibit solo.

“It was my first chance to see the show I had envisioned come to life,” he said. “Honestly, the best moment for me was being there alone, immersed in the work. I was born in 1982, and Lee Krasner passed away in 1984. This felt as close as I could get to spending time with her personally.”

When he asked me what my favorite painting was, the answer came easily — “Number 2, 1951.” It was far more imposing in person than on the page, and its unexpected muted but exquisite palette of warm terracotta, soft peach, dusty rose, and hints of ochre and slate blue struck me from just a few feet away.

Kasmin’s researcher, Jason Drill, said it was the largest painting from Krasner’s Betty Parsons show and that it was painted on the second floor of the home in Springs. “She had an unstretched canvas precisely the size of the largest wall,” he said.

I silently wondered whether she would have painted more large-scale works if she hadn’t been confined to the bedroom, unlike Pollock, who had the barn. Might she have aligned more closely with other abstract artists, given that their large scale partly contributed to their recognition?

Soon, the gallery would welcome the public. Before the doors were opened, the people I knew in the room left for other Thursday openings, and for a few minutes, the gallery was almost empty. I was surrounded by Krasner’s paintings, and at that moment, language, always my friend, seemed inadequate to capture the depth of what I was experiencing. The art moved my narrative brain, so I stopped trying to analyze it and felt it deeply.

A message from our CEO & publisher Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO