It was the biggest painting in the world — how could it just disappear?

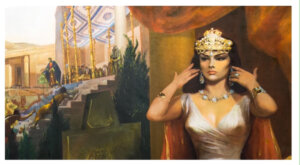

In 1959, millions of Americans saw Symeon Shimin’s mural of Yul Brynner and Gina Lollobrigida as Solomon and Sheba. Then it was gone.

Symeon Shimin faces an empty canvas. Courtesy of Toby Shimin

Big. Big, big, big.

That’s what Gina Lollobrigida was in 1959 when she was the hottest, sexiest, most talked-about actress in the world. That’s what the movie Solomon and Sheba was too: a $6 million biblical spectacle directed by the legendary King Vidor, with grandiose sets, sumptuous costumes, and a star-studded cast. United Artists’ publicity budget alone for this extravaganza was $2 million (more than $20 million today).

But the biggest big was actually an oil painting, 40 feet wide and 11 feet high.

On a bitterly cold day in mid-November 1959 — before it wowed the Hollywood elite, before it toured the world, and before it mysteriously vanished — the largest single canvas oil painting in the world sat snugly behind red velvet curtains in the Grand Ballroom of Chicago’s 757-room Sherman Hotel. Clinks of glasses and murmurs of deal-making were heard in a haze of cigar smoke as models in clingy outfits inspired by the film mingled with married men. Everyone there agreed that UA’s costume designers had worked hard to get the very most out of the very least.

The film had had its 70mm grand premiere at the Astoria Theatre in London on Oct. 27, and now the promotional team had devised an innovative strategy to generate buzz for the American release: a colossal traveling painting that would be revealed at the 11th annual Theater Owners of America convention. Entertainment reporters were awarded solid gold Tiffany medallions with their names engraved for “unbiased” reporting. Prior to the convention, photos had been leaked of The World’s Most Beautiful Woman sitting for the artist in his Greenwich Village studio.

The unveiling came after the last bite of cheesecake. United Artists’ 46-year-old vice president Max Youngstein stepped forward as the lights dimmed. This would be the mightiest motion picture ever made, he declared, the first live-action film to use Super Technirama 70, which would provide a more cinematic experience. Youngstein pulled a cord and revealed the colossal canvas, a rich tableau featuring Yul Brenner as Solomon, the Israelite king, preparing to enter battle, and Gina Lollobrigida as the seductive queen Sheba, in a moment of intimate contemplation. Applause broke out in the room.

The following day, the public was permitted into the hotel, allowing Chicagoans to see the canvas before anyone else in the country. It would travel around the U.S. for about half a year.

Italian bombshell Gina Lollobrigida died this month at 95, and her lusty portrayal of Sheba was forever captured in the movie and the mural. But what about the tortured artist who painted that mural? And what became of the mural itself?

How could the world’s largest oil painting just disappear?

The man behind the mural

Symeon Shimin was a 57-year-old bohemian Jewish man haunted by his past. Six feet tall, lean and mustached, Shimin had spent his early childhood in the Russian city of Astrakhan, a thriving hub of trade and industry at the mouth of the Volga river. Here, east met west, and he later recalled caravans of camels plowing through the streets and streetcars that ran on electricity. The Shimins were wealthy; he lived in a large three-story European-style house with his grandparents, parents, two younger brothers, an infant sister, his two uncles, and his family’s household staff.

The early 1900s in Europe were terrifying times for Jews, even those with money. Symeon’s father, Nachman, a skilled cabinetmaker with a store, used antiques as bribes to protect his family and friends from conscription. His vzyatki (kickbacks) did the trick.

Symeon left his childhood home for good at the end of May 1912. After two weeks of cramped train travel to Latvia, the family boarded their ship with their steerage class tickets at Libau on the Baltic Sea (now Liepāja). A band played marches as the vessel slipped out onto the open sea. It was only weeks after the Titanic crash, and onboard, passengers were still anxious and talking about the disaster. When the sea misbehaved, it didn’t help. But after 14 rough days, the SS Russia arrived in New York at 5 a.m. on Jun. 26, 1912. Symeon and his family were greeted by his uncles — jeweler Paul and the musical Eli, bachelors who had served as the advance party.

The lives the family had led before were privileged, but not anymore. After tickets and bribes, all 32-year-old Nachman had was $150. The family moved into a miserable Lower East Side railroad flat. Nachman Shimin became Nathan Simkin, and Symeon Shimin became Samuel Simkin on his first day of public school.

Although demoralized and determined to return to Russia, Nachman’s relatives urged him to try a new career. He opened a delicatessen in Bushwick, Brooklyn. On the second day of the operation, Symeon’s baby sister Chaye died of the lingering pneumonia she had contracted on the ship.

Symeon’s orthodox education at the cheder had been devoid of math and other essential skills, and when he entered first grade at the age of 10, he towered over his classmates. Bullies in older grades were eager to humiliate him, but one teacher gave up her lunch period to tutor him, and because he was such a quick learner, he skipped five grades in one semester.

Instead of playing a real instrument, Symeon carved a cross between a violin and a guitar out of wood, a Frankenstein of bow and strings. At 12, he finally dared to tell his parents he wanted to study music, but Uncle Eli, whom he idolized, had a fit. What was the point of being poor like him? The family needed a doctor or a lawyer! His parents agreed. The despondent child, who never had an interest in art, began drawing on brown paper bags from the delicatessen, and his sophisticated doodling stunned his family.

Symeon Shimin abandoned high school at 16 and apprenticed with a commercial artist. He received a scholarship to Cooper Union, where he studied for free.

While his family continued to use the anglicized name Simkin, at 21, he changed his name back to Symeon Shimin to reclaim his early Russian-Jewish identity. He used art school connections to get assignments to design Jazz Age magazine covers; one featured a lean-legged lady dancer on the January 1929 cover of Vanity Fair just months before the crash.

Although he dreamed of being a “real artist,” he was by no means the only tortured talent who relied on selling commercial art to make ends meet. Dutch stowaway Willem de Kooning also trained as a commercial artist and worked as a billboard painter and illustrator. Mark Rothko began commercially too.

Shimin befriended the titans of 20th-century American art, frolicking on the beach at Amagansett with the likes of Willem and Elaine de Kooning. At the same time, he forged close relationships with three frequently forgotten Jewish brothers, Raphael, Isaac, and Moses Soyer, whose realistic work better matched Shimin’s own.

During the late 1930s, he painted the stirring mural Contemporary Justice and the Child for the U.S. Department of Justice building in Washington, D.C. This work was commissioned by the Public Works Art Project and can be seen today on the third floor, behind the Great Hall.

Though he was a lifelong pacifist, when he was asked to do recruitment and war bond posters during World War II, he obliged, particularly since Eleanor Roosevelt was involved.

But mural commissions and government work weren’t enough, and he had to continue to rely on his commercial skills, even producing perhaps the most iconic film poster for Gone With the Wind. During one miserable stint in the early 1940s, he worked as Howard Hughes’ personal artist and soon learned that Hughes always wanted more cleavage in his work. As a result, he routinely painted two paintings for his eccentric boss. If Hughes didn’t like the first one, Shimin would whip out a second painting with more boob.

But when Hughes asked him to do some private pornography, Shimin had enough and returned to freelancing film posters. He quickly became one of the country’s highest-paid artists, but the fact that his money came from film posters, while his formerly broke old drinking buddies were commanding top fees at galleries like Betty Parsons, Sidney Janis, and Art of This Century, shamed him.

The artist confronts a dilemma

By 1959, Shimin faced an artistic dilemma that came in the form of two phone calls. In one, the Whitney Museum called asking if they could display a current work in progress, The Pack (1959), for their Annual Exhibition of American Art. The oil painting was based on his experiences of being attacked by a pack of thugs on a New York street after intervening in a helpless boy’s defense. Somewhere between abstract and realist, entangled figures appear to be metamorphosing into hyenas and jackals.

The second call came from United Artists offering an enormous commission for a mural for their upcoming blockbuster Solomon and Sheba and the poster for the movie.

Much of the film had been shot in Spain in 1958, but the original actor playing King Solomon, 44-year-old heartthrob Tyrone Power, had a heart attack after a Nov. 10 dueling scene and died five days later. Now, the studio had decided to reshoot the movie with Yul Brynner at the cost of an additional $2 million, and a sizable portion of that budget would flow directly to Shimin.

This news wowed Shimin’s new bride, Rosa Rosenblatt, a 35-year-old newly divorced copy editor. Yes, she wanted to encourage his art, but he owed alimony to two other wives, didn’t he? He decided to accept the commission and also finish his work for the Whitney.

After buying the largest available piece of blank canvas available in the world, he assembled a team of five assistants to help him with background and fill-in work. He also hired 10 live models. In a manner reminiscent of the Renaissance, Shimin and his team clocked over 4,000 hours. Reportedly, he worked for 145 days, using 472 brushes, as well as 215 pounds of paint. Shimin worked 16-hour days to complete the painting in time for its tour, as he was desperate to return to his “serious” art.

By Oct. 4, 1959, the mural was nearly finished. That’s the day when 32-year-old Gina Lollobrigida and her posse came to Shimin’s West 11th Street studio, wearing a flowing pearly pink day dress tight at the bosom, a glamour girl’s civilian attire. The 57-year-old Shimin posed theatrically over the actress with a palette and easel. “I used some of the script and some still shots for ideas,” he told a reporter.

There was still, however, the question of how to get the mural out of his studio. On Nov. 7, the artist seemed near tears; ten teamsters had arrived at his Greenwich Village studio, but they couldn’t get the mural, rolled up and tucked in an enormous crate, out the door. As was the case with some of the giant abstract paintings of the day, the only way out was through the window. The mural was swung from the second-story window and lowered in a sling of ropes to a truck.

With the mural out of the way, Shimin went back to work on his painting for his upcoming Whitney show, where his work would be shown in December alongside that of Edward Hopper, de Kooning, Joan Mitchell, Georgia O’Keeffe and Jasper Johns.

Meanwhile, the giant mural was on its way to Chicago for the TOA trade show with a quarter-million-dollar insurance policy. With two armored guards by its side, the canvas, along with its case, weighed half a ton. After Chicago, it would embark on a tour of other cities, including Boston’s South Station, Philadelphia’s 30th Street Station, and Pittsburgh’s Alcoa Building lobby, before arriving at New York City’s Penn Station on Dec. 2. It was displayed on the newly renovated Long Island Railroad level, where it was seen by 1 million commuters. Since the mural was too heavy to hang, it was placed on a platform adjacent to the clock.

Viewers stared in amazement. Al Bauer, a construction worker from North Merrick, and Mitch Cotton, a salesman from Syosset, said they wished they could take the mural home. A roving reporter spotted veteran Knicks player Ernie Vandeweghe, who expressed surprise at seeing Yul Brynner’s arms around an eight-foot-tall Lollo. “For that, they blew the whistle in our league,” he said.

“Choice Italian Dish Dominates the Station” was the headline of New York’s Weekend Sun.

Following its Christmas debut in New York, Shimin’s painting toured smaller American markets and Canada up until spring 1960. Though it would later be included in the 1978 book The Fifty Worst Films of All Time, Solomon and Sheba grossed over $12.2 million, thanks in large part to Lollo.

Gina was ecstatic about her payout. And, given his alimony bills, so was Shimin. Like many enmeshed in Hollywood, he hated the work but loved the money.

Soon, though, with the rise of television, big money for film promotion dried up. Shimin soon became desperate for work, and friends connected him to book projects that paid him enough to live on. And illustrating children’s literature did not offend him in the same way as painting va-va-voom.

During this time, Symeon became a father again. Toby Shimin, Symeon’s second daughter from his third marriage, remembers him as an older parent smelling of turpentine. He was always in jeans, black turtlenecks, and corduroy.

Tonia Shimin, his older daughter, a dance professor, recalls much more, including the ugliness of the earlier divorce. Despite being 18 years apart, the half-sisters have always gotten along well. In separate phone interviews on different coasts, they described their father as warm with a magnetic personality — and a ladies’ man. (When he was in his 80s, he had a girlfriend in her 30s.)

Though he never became a household name as a “serious artist in museums,” he illustrated 57 children’s books, and won two prestigious Christopher Awards, for work exemplifying the “highest human spirit.”

Despite plans in his eighth decade for another serious painting themed on liberation, Shimin died of cancer in 1984 at 82. After the funeral, his daughters sorted through his belongings and surviving artwork, which did not include the mural.

And then it vanished

Years ago, Toby Shimin, a film editor I knew from the documentary world, told me about the World’s Largest Oil Painting, but she didn’t tell me the whole story about it until now, after Gina Lollobrigida’s death.

In 1960, the painting was rolled one last time over a steel tube, then encased in a larger, unique three-quarters-inch-thick plywood tube with a collapsible metal framework, all contained within an enormous plywood crate.

Did the artist know the painting’s whereabouts after that? Did he even know where it was stashed? From 1960 until 1983, Shimin’s mural was likely on the property of United Artists, who sold their company to MGM in 1981. But that’s just a guess. Even though his daughters have some of his finest paintings and an archive holds his children’s book artwork, no one in the family knew where the mural was.

In early 2019, Shimin’s grandson Shamus Donlon was internet surfing when he discovered a picture of the mural hanging in the Detour Gallery, a contemporary art gallery in Red Bank, New Jersey. But the photos had been taken a few weeks earlier, the mural had been put back into storage, and the owner was overseas. Tonia Shimin, his mother, wanted to include the mural in a coffee table work, The Art of Symeon Shimin. The gallery assistant provided some excellent photos of the mural, but it was different from seeing it in person.

Was it doomed to remain in storage indefinitely? And where was it now?

How the World Tour stopped in New Jersey

Turns out that Solomon and Sheba are alive and well, and living in a crate in New Jersey.

I got a call back this week from Kenny Schwartz, 71, who owns the Detour Gallery. “When you grow up in pain,” he told me over the phone while he was driving home on the New Jersey Turnpike, “you find relief in acquiring things and opening boxes. I used to own a Jeep dealership and now own several restaurants. I’m a fucking nut, a compulsive entrepreneur. There’s so much stuff I’ve collected over the years. Some of it is on the wall, and the pricey stuff is in the vault. I got a Mary Cassatt, early Basquiat work, and what I think is the biggest collection of letters written by Billie Holiday.”

I laughed when he told me he had Lex Luthor’s dystopian paintings from one of the Batman movies in storage. “When I bought those, I was on a collecting high,” he said in his thick Brooklyn accent. “I’m sure they’re somewhere. Searching through all 6,000 artworks would take a long time. I may even have some Shimin paintings I got on eBay.”

Could he recall the day he bought the mural?

Yes and no.

“It was 40 years ago, probably around 1983,” he said. “Everything before I got clean from drugs and alcohol in 1987 is fuzzy. Man, I was so fucked up on something that day, who knows what, and I was a compulsive buyer at an auction. I peeked at this crazy crate and rolled out a bit of mural, just a few inches. Whatever it was, it was interesting, and I wanted it and didn’t want to draw attention to it and have other buyers interested. I was the only one bidding on it, and then I worried about how the hell I would get the thing home. Even though I was drinking, stoned, or possibly both, I called for a flatbed at the closest gas station. After I got it home, I stored it for decades, never hanging it until 2012 for a few weeks in Neptune, New Jersey.” This was in another one of his “crazy” spaces called American Antiques Company. It was briefly hung again in his gallery in Red Bank in 2017.

Schwartz said he keeps the mural in its crate in his gallery and covers it with marble. “It’s our coffee table!” Last month, when he read about Gina Lollobrigida’s death, the fact that he owned a mural with an eight-foot Gina didn’t even occur to him.

Schwartz also told me he believed this painting deserves to be seen by many people — maybe in an offshoot of Detour Gallery that he plans to open next year in Chelsea.

“I think I need a space with walls tall enough to hang the mural,” he said. “What do you think?”

So yes, God willing, it seems Gina Lollobrigida will take a final bow! And perhaps, though Symeon Shimin might be appalled to be remembered by a crass promotional stunt, it will finally draw more attention to his beloved serious art.

The Forward is free to read, but it isn’t free to produce

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward.

Now more than ever, American Jews need independent news they can trust, with reporting driven by truth, not ideology. We serve you, not any ideological agenda.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

This is a great time to support independent Jewish journalism you rely on. Make a gift today!

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO

Support our mission to tell the Jewish story fully and fairly.

Most Popular

- 1

Fast Forward Ye debuts ‘Heil Hitler’ music video that includes a sample of a Hitler speech

- 2

Opinion It looks like Israel totally underestimated Trump

- 3

Culture Is Pope Leo Jewish? Ask his distant cousins — like me

- 4

Fast Forward Student suspended for ‘F— the Jews’ video defends himself on antisemitic podcast

In Case You Missed It

-

News In Edan Alexander’s hometown in New Jersey, months of fear and anguish give way to joy and relief

-

Fast Forward What’s next for suspended student who posted ‘F— the Jews’ video? An alt-right media tour

-

Opinion Despite Netanyahu, Edan Alexander is finally free

-

Opinion A judge just released another pro-Palestinian activist. Here’s why that’s good for the Jews

-

Shop the Forward Store

100% of profits support our journalism

Republish This Story

Please read before republishing

We’re happy to make this story available to republish for free, unless it originated with JTA, Haaretz or another publication (as indicated on the article) and as long as you follow our guidelines.

You must comply with the following:

- Credit the Forward

- Retain our pixel

- Preserve our canonical link in Google search

- Add a noindex tag in Google search

See our full guidelines for more information, and this guide for detail about canonical URLs.

To republish, copy the HTML by clicking on the yellow button to the right; it includes our tracking pixel, all paragraph styles and hyperlinks, the author byline and credit to the Forward. It does not include images; to avoid copyright violations, you must add them manually, following our guidelines. Please email us at [email protected], subject line “republish,” with any questions or to let us know what stories you’re picking up.