A Blockade That Doesn’t Apply to Lulavim

When Israel recently opened a loophole in its blockade of Hamas-controlled Gaza, it wasn’t heeding international calls to loosen its closure for humanitarian reasons. Instead, Israeli officials were spurred to action by the Jewish holiday of Sukkot.

On September 29, Israeli Defense Minister Ehud Barak approved the immediate importation of palm fronds, or lulavim, from Gaza in advance of the harvest festival. According to the Israeli daily Ma’ariv, Barak was responding to appeals from Israel’s minister of religious services, Yakov Margi of the ultra-Orthodox Shas party.

With a shortage of palm fronds, Margi reportedly feared that Israelis would be forced to pay exorbitant prices for lulavim, one of the four plant species used in Sukkot rituals. Margi thanked Barak for the decision, saying that it “prevents the possibility that the merchants’ cartel will utilize the shortage at the expense of the consumer’s pocket.”

Not every Israeli politician, however, approved of the decision. Michael Ben-Ari, a Knesset member from the far-right National Union, called on Israelis to pay a few shekels more for, as he put it, “Jewish-grown” lulavim. He said that the importation of palm fronds from Gaza is a “crime” because it supports Hamas.

There is a crime here, but not the one Ben-Ari thinks.

Israel’s current blockade of Gaza began after Hamas seized control in June 2007. Since then, Israel has severely restricted Gaza’s imports and exports. Gazan farmers have been mostly unable to get their crops to market in Israel, the West Bank and abroad. Gaza’s carnation producers alone lost millions of dollars last year, Oxfam recently reported. Fields now lie fallow as Palestinians have given up on selling their products overseas; hundreds of families have lost their livelihoods.

But it isn’t only farmers’ crops that are prevented from leaving Gaza. According to Physicians for Human Rights-Israel, approximately 40% of the requests to exit Gaza for medical treatment are denied every month. Palestinians who study overseas sometimes find themselves stranded in Gaza, unable to pursue their educations.

Meanwhile, Israeli authorities continue to erect new hurdles. Only two weeks before the decision to allow in the palm fronds, Israel’s Gaza District Coordinator Office informed several Israeli NGOs that assist Gazans in getting travel permits that it would no longer communicate with them on such matters, effectively shutting off yet another avenue of recourse for trapped Palestinians.

Human rights organizations have denounced the Israeli blockade as collective punishment. “Israel is using one-and-a-half million human beings as political pawns,” said Keren Tamir of the Israeli NGO Gisha, which advocates for Palestinians’ freedom of movement.

Israel, for its part, maintains that the blockade is necessary to weaken Hamas. It defends the closure as a response to ongoing rocket attacks from Gaza and to the 2006 kidnapping of Israeli soldier Gilad Shalit.

Yet palm fronds now have a green light to pass through the border.

At first glance, this development seems like a win-win situation — Israelis get cheaper lulavim, Palestinian farmers get some much-needed money. But there is something deeply troubling about Israel’s willingness to ease the blockade, but only for its own benefit. It suggests that Israelis place a higher value on shaving a few shekels off the price of lulavim than we do upon alleviating the suffering of ordinary Gazans.

During Sukkot, we forsake the comforts of our homes in order to recall the vulnerability of our ancestors as they wandered the desert after escaping captivity in Egypt. It should also be an opportunity for Israelis to look beyond our own legitimate security needs to also consider the vulnerability of our neighbors.

Mya Guarnieri is a freelance journalist based in Tel Aviv.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

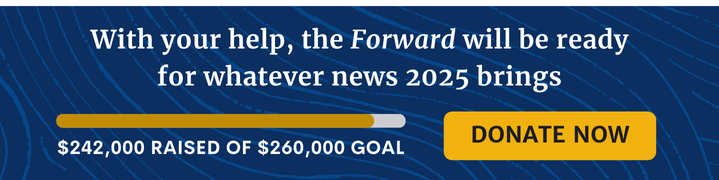

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO