The Doctor Who Had the Chutzpah To Write Music

Retired radiologist Albert Hurwit knows a thing or two about success. The Hartford, Conn., resident — and grandfather of eight — has a pedigree fine enough to make any mother kvell.

Undergraduate education from Harvard University? Check.

Medical school degree from Tufts University? Hurwit’s got that, too.

Founder of a radiology practice that has multiple offices in the Greater Hartford area? Done and done.

But according to Hurwit, a humble man despite his accomplishments, he has never won an award. And that’s why he was taken aback on a Sunday night a few months ago, when he received an unexpected phone call. The man on the other line told Hurwit, who had just settled into an evening with his usual cocktail, that he won the 2009 American Composer Competition, a biennial event. And just like that, Hurwit’s symphony submission, based on his family’s story of Old World persecution, separation and renewal, brought him his first award at age 78.

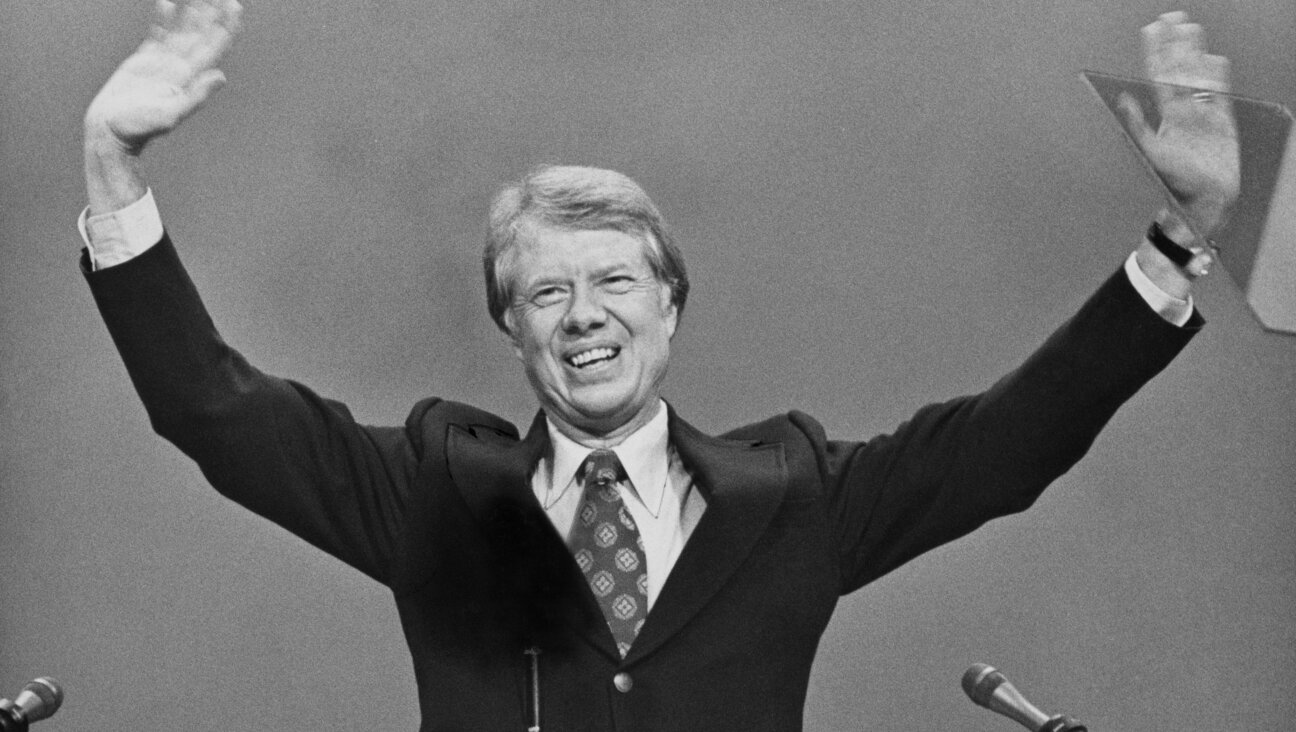

Memories: Hurwit wrote his symphony to reflect the struggles that his mother?s family, the Milkowitzes (above c. 1912), endured.

Out of 124 submissions received last spring, Hurwit clinched the top spot with “Remembrance,” the third movement of his four-movement Symphony No. 1.

What’s remarkable about Hurwit’s win is that the composer can hardly read or write music. In fact, before making the decision to become a doctor, he was denied enrollment in the music school at Harvard because he couldn’t sight-read.

“I read like a second-year piano student,” said Hurwit, who took a few years of piano lessons as a boy, although he was quick to add that he’d rather have spent the time playing baseball. Although he has always been passionate about music, Hurwit recognizes that he may come across as “the guy who never studied music and had the chutzpah to write a symphony.”

But Hurwit’s tale of unexpected musical success is a tribute to the possibility of pursuing a dream despite unlikely odds.

Maryland’s Columbia Orchestra, which oversees the American Composer Competition, will perform Hurwit’s winning movement December 5. The orchestra’s judges reviewed the musical scores without the composers’ names. The judging panel learned the identities of the competion’s winner and seven finalists only after they scored the competition.

The music director of the orchestra, Jason Love, said that typical winners of the competition are younger composers who often hold university positions teaching music.

“It was fascinating to have someone who had taken a different track,” he said.

According to Love, Hurwit’s entry stood out because the slow movement was able to sustain the judges’ interest. More often, composers submit up-tempo performance pieces in hopes of impressing the judges.

But it was Hurwit’s composition, and his story, that impressed the judges.

In 1986, Hurwit retired at age 55 from the radiology practice that he founded, Medical Imaging Center, to pursue music composition full time. While he did not begin writing Symphony No. 1 until 2000, Hurwit said he incorporated into the musical work melodies that he composed as a teenager.

“Part of the symphony to me is a legacy,” Hurwit said.

That legacy draws on the personal history from his mother’s family. “Origins,” the first movement, recalls the 19th-century journey that his mother’s family, the Milkowitzes, made to Russia from Prague. The second movement, “Separation,” focuses on a pogrom attack against his family in the late 1880s that prompted the family elders to send the youngsters to America. “Remembrance,” the third movement, centers on the family’s deep sorrow at the pending separation. In the fourth movement, “Arrival,” the young Milkowitzes set sail for the Promised Land of the Diaspora, America.

While the bulk of Hurwit’s symphony is situated in the Old Country, the composer said he has memories that relate to it from his childhood in the United States.

“I remember my Aunt Grace telling me how she took my mom’s hand and ran into the attic,” Hurwit recalled, referring to the pogrom that prompted some members of his family to immigrate to the United States, leaving others behind.

“In the second movement,” Hurwit said, “you hear three ascending notes, which is the elder saying, ‘You must go.’ Then the younger ones say, ‘No, no, no.’”

In order to write the third movement of the symphony, Hurwit said he put himself in the harrowing position of his ancestors — albeit within a modern context. “The third movement is the searing sadness of the [tear] in the family. Part of that was me sitting back here, saying, what if I walked out to my backyard with my wife and three married children. I said, ‘Your mother and I are staying here, but you must go, and we’ll never see each other again.’ I hope that comes out in the music,” Hurwit said.

Hurwit composes in a home study that is filled with electronic equipment. A keyboard connects to a computer system, which transposes the sounds he plays on the keyboard into notes on a line. If Hurwit is out on the town when he gets a melody in his head, he either hums the tune into a recorder or takes a piece of paper and graphs it with dots that are relative to each other.

It was these musical tendencies that led Hurwit to apply for acceptance to Harvard’s music school in the first place, but after being denied, “I became a doctor instead,” he explained.

Asked if he sees a connection between his work in radiology and composition, Hurwit offered an unequivocal no.

“I find enormous contrasts,” Hurwit said. “It [composition] has to come not from the head — the brain — but the heart.… Composing music to me, the basis of it, is un-intellectual.”

As a diagnostician, Hurwit described himself as the “tyrant of being objective.” After all, if you blink once at an inopportune moment, that could mean trouble for the patient. With music, however, it’s the exact opposite, an experience where the filters are off and emotion is allowed to color the experience.

Emotion is exactly what Love is busy capturing. Rehearsals for “Remembrance” began on October 19. And while Love said the movement is not overwhelmingly technically challenging, it is musically demanding. The trick is coaxing out the musical subtleties from the depths of the composition.

Love noted, “That’s what musicians really love.”

For information and tickets, visit www.Columbiaorchestra.org.

Hinda Mandell is a doctoral student in mass communications at the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications, Syracuse University.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO