What’s in a Name?

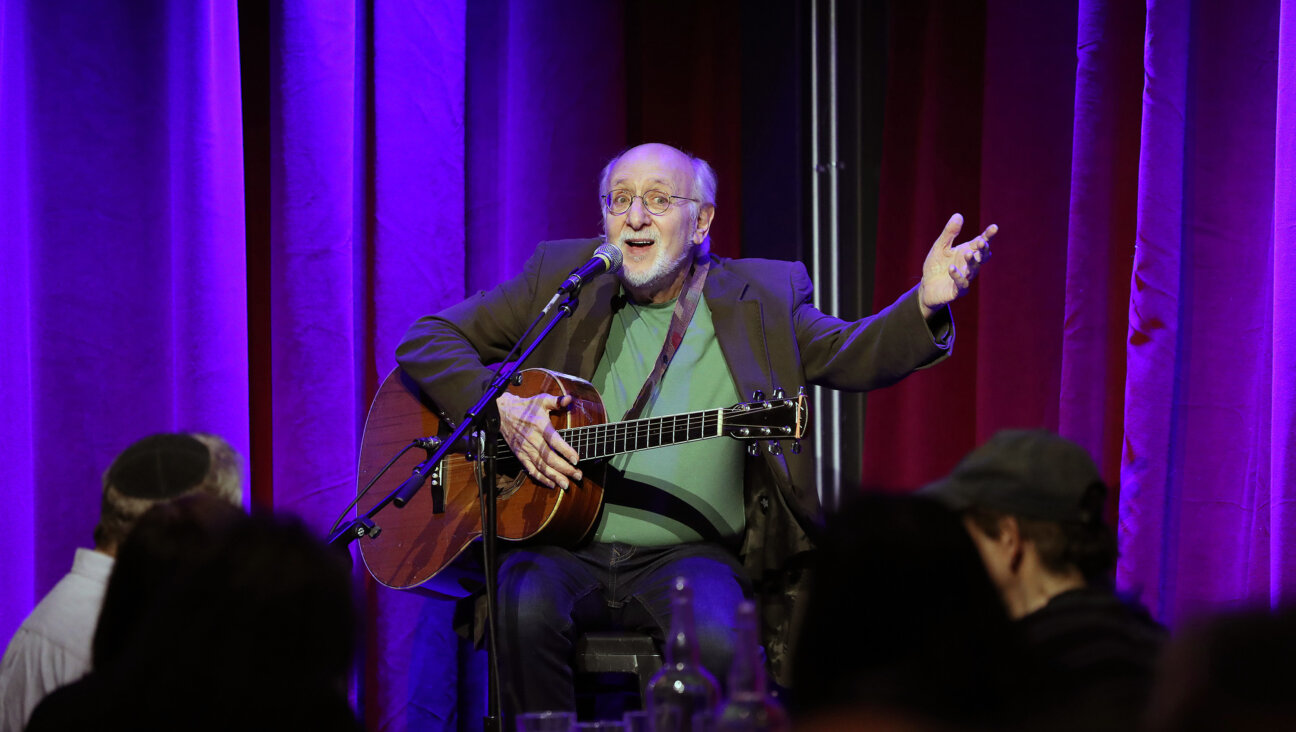

Shayna Punim: Sarah Wildman and her husband, Ian, struggled for months to choose a name for their daughter that reflected their dreams for her future as well as her roots. Image by courtesy sarah wildman

My mother always regretted my middle name — Amy. She rues not giving me Lewis, her maiden name, which, to be honest, would have been cool, a wink at masculinity; meaningful. Sarah was a given, she’d known from childhood she would have a girl named Sarah. Sarah was for her mother who died, too young, when my mother was only 9. But, being a fairly typical Ashkenazi family, we had several Sarahs. My mother’s choice allowed everyone to assume I was named for theirs. It made them happy, even if technically it wasn’t true. How my mother knew with such certainty the sex of her first child I never understood, but there I was, pink and screaming, a week late, Sarah from the moment I first drew a breath.

And I have, true to my mother’s fidelity to the name, always loved Sarah. Sure, there were times I thought I’d like something more modern. I liked Tamar, especially when on a particularly Zionist kick in middle school. In Israel, as a teenager, my friends mockingly told me Sarah, so earnestly biblical, was only for saftas and suggested I swap it for Sarai. But Sarah actually suited me just fine. I liked the h, especially, felt it closed the name. And Sarah travels well. Pretty much everyone can say Sarah. A good chunk of the world has a Sarah in their lives: Muslims, Christians, Jews. I liked that: It was Jewish but incognito, hidden in plain site.

And yet when it came to naming my own daughter I was at a loss. We found out in August 2008, when I was living in Berlin, that I was carrying a girl. “The Little Jew,” we called her, when we wanted to get a response; “Snow Pea,” or “Pea,” when we referred to her among friends — those first sonograms look a bit like pea shoots. But her real names eluded us. And when the labor began, four days past due, we were no closer to knowing. We envisioned nightmare kindergarten scenarios: children gathered ‘round, “Your name is…Pea?”

For months my partner Ian and I weighed whom we wanted to honor with her name. There were six grandparents to consider. In good Ashkenazi tradition, we planned to name for the dead. Though envious of our Sephardi cousins, we were too superstitious to honor the living. We were both particularly interested in remembering our paternal grandparents, though Ian’s mother told us we needn’t consider his grandmother. She already had someone named for her.

But mostly I was held back by the awesomeness of the task. A name Ian and I discussed over countless dinners and late nights, and then, nearly panicked, under hospital fluorescent lights, represented both our dreams for our child as well as the roots that brought her, and us, to where we are today.

If that weren’t heavy enough, we had a long list of needs: We wanted her name to be modern but not trendy, to be pronounceable in every mouth around the world (or at least a good majority of mouths), to be forward thinking, to mean something, to be backward glancing, to stand firmly on the shoulders of her ancestors and yet propel her easily into the future.

I’d always assumed I’d give my child an Israeli name. Facing the actual kid, we were given pause; we were American Jews, after all. What kind of Jew did a name make her? Would a name shape a kid too much? I have a cousin in Israel everyone calls Cami. He’s my father’s age. His real name is Nechamiah*, my revenge*. His father Ruben’s first family was all murdered. Cami was, literally, revenge.

As we pondered, I was deep in a project about my grandfather. Chaim Judah Wildman fled Austria six months after the Anschluss. His sunny world view and cosmopolitan mien were things I was keen for my daughter to inherit. We decided, as much as my middle name had meant very little, our daughter’s middle name would bear weight: We would give her Chaim.

Yet we remained stumped for the first. Orli had made the early lists: my light. We liked the meaning, we liked the O. It also fit my grandfather’s unique ability to see the light in every situation. A story we like to tell found him arriving in Hamburg, on the run from Vienna. “Who knows if I’ll have a chance to see the city again?” he is said to have said, and struck off to tour the town.

But having lived in Europe for some years, we feared that people would assume she was named for Orly Airport, just outside Paris, as though she were conceived there, like David and Victoria Beckham’s son, Brooklyn. Yech.

So we left that name and tried others. We feared Ma’ayan would stumble teachers on the apostrophe; we lingered over Tal and Noa, liking the androgyny.

When she finally came into the world, after 36 hours of labor, my sister turned to me and said, “I love the name Noa, but I think she’s an Orli.”

And still we debated. We made the mistake of floating ideas out to family and friends. “Chaim?” My relatives said, seizing on the one solid ground we had. “Why not Chaya?”

And then, it became clear. We didn’t care that some people thought it was a secondary airport, or that Chaim is for boys. She was sweetness and light and a new life. Orli Chaim Wildman Halpern was named.

From the outset it was a decoder ring. In the new-moms group I joined, an Ecuadorean woman named Karen came up to me and said, “Orli was on our short list of names!” And so I knew we were from the same stock. Non-Jews think it’s pretty, and unusual; Jews nod.

And Orli carries the sunny disposition of her great-grandfather, as well as, so far, his precocious inquisitiveness and his ability to connect with random strangers.

Of course, when we traveled with her in Spain this past summer, most people believed her to be named for the airport, yet everyone embraced the idea of “mi luz.” And in December, when we shopped for Hanukkah gifts in a Dupont Circle dry goods store, the Israeli shop owner asked me her name. “Is she your light?”she asked with a knowing wink. She is, indeed.

Sarah Wildman writes about the intersection of culture, politics and travel for the New York Times and the Guardian.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO