Why Jews Must Never Let Go of Their Liberalism

Image by Nikki Casey

In these dark days of post-election despondency, I have managed to cling to a slender reed: Jewish liberalism. According to a Pew Research Center survey, Donald Trump won a majority of every other religious group: Catholics by 52% to 45% (non-Hispanic white Catholics, naturally, 60% to 37%); Protestants, 58% to 39%; evangelicals and born-agains, 81% to 16%; Mormons, 61% to 25%. Muslims weren’t tallied separately, though a bucket titled “other faiths” favored Hillary Clinton, 62% to 29%. And then there were Jews. They voted for Clinton 71% to 24%. So consider this: If only Christians had voted, Donald Trump would have won the presidency by roughly 60% of the vote — a landslide. There is a frightening thought for you.

I have never been more proud to be a Jew than at election time. While every other religious group is voting its prejudices or venting its malice, the overwhelming majority of my co-religionists are voting their compassion and their better angels. Anti-Semites, who are mostly drawn from conservative ranks, see this as yet another cause for vilification. For them, liberalism is an awful reflex, born of some seditious impulse that Jews have to blast bedrock America. This was, by the way, the justification conservatives used back in the 1910s for trying to wrest the film industry from the Jews who ran it: Jews didn’t understand American values. Whether or not we understand so-called American values, we seem to understand human values.

Modern liberalism arose during the Great Depression primarily as a form of self-interest. People were in distress. They needed the government to help them, and help them it did, creating the modern welfare state. Most Americans embraced it — gentiles and Jews alike. We lived for a time in a liberal country.

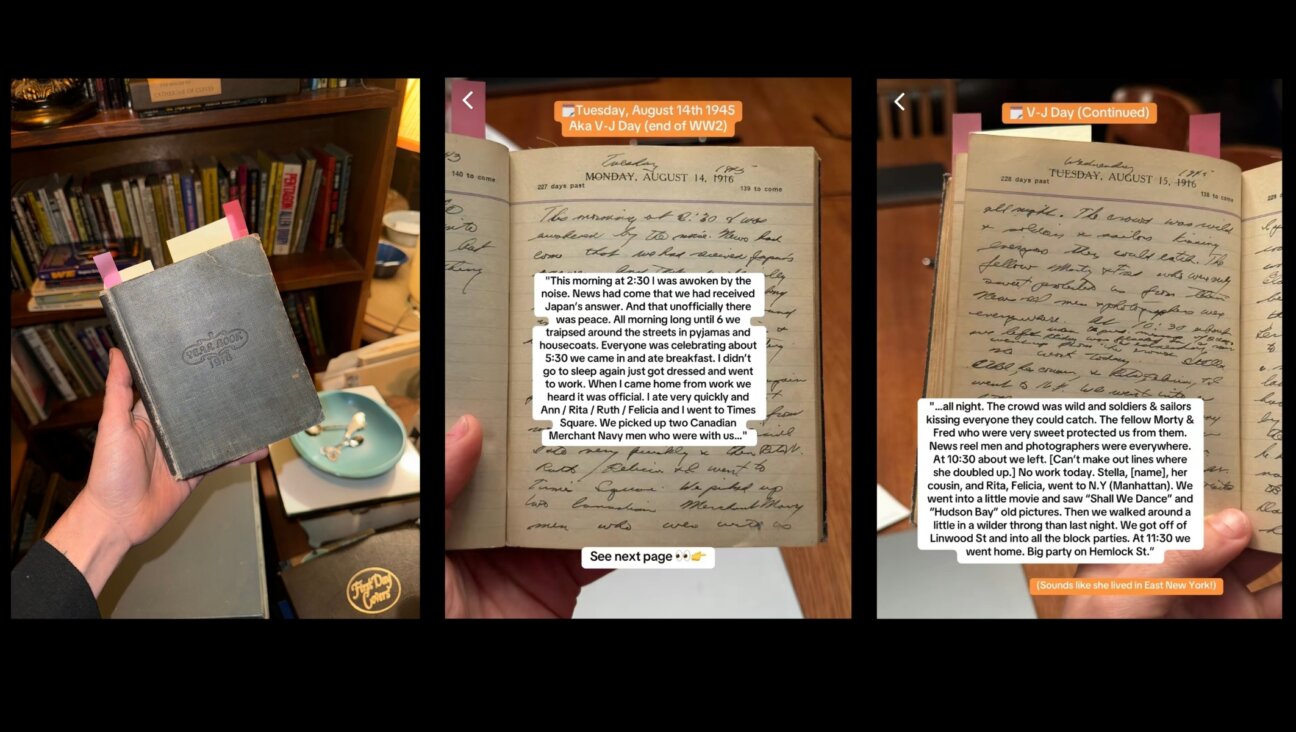

But Jewish liberalism was always a bit different from that of the majority of Americans. While it certainly had an economic component, that seemed to be only a small part of the attraction. Jews, as a hated minority, always knew how tenuous their existence was. History had proven it. The generosity of liberalism, its underlying concern for the vulnerable and the marginalized, of which Jews certainly considered themselves, made for a more powerful pull for Jews and other minorities. In my family as, I suppose, in most Jewish families, Franklin Roosevelt as the father of modern liberalism was a deity, right up there with Yahweh. In “Portnoy’s Complaint,” Philip Roth’s titular hero describes how his parents lit a sabbath candle for Roosevelt every Friday. My parents and grandparents lit that candle too.

When the Depression ended and America luxuriated in postwar prosperity, thus seeming to obviate the urgent need for a welfare state for most Americans, liberalism somehow hung on. Eisenhower could have tried to revoke Social Security, unemployment insurance, the National Labor Relations Board and other New Deal programs, albeit against fierce Democratic opposition, but he didn’t even consider it. He appreciated that Americans had rapidly come to consider them part of the American way. Instead, over the next decade, under John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson, liberalism expanded. To me, this is one of the great mysteries, and glories, of American politics. The Republican drumbeat for lower taxes, nativism, increased hostility to minorities, and an end to most government safety-net programs didn’t knock liberalism from its perch until Reagan arrived in the 1980s.

I suspect that liberalism held on not because white middle-class Americans perceived that they benefited from it, even though nearly all of them did. In fact, Republicans constantly told them that they didn’t, and even today, most Americans seem to have no idea that their beloved Medicare, which the new Republican Congress is threatening to dismantle, is a government program devised by liberals. It held on, I believe, because it possessed the vestiges of what I would call “moral authority,” which is to say that Americans, deep in their consciousness, before evangelicals and others corrupted the national conscience, knew liberalism was the ideology of decency, and conservatism the ideology of selfishness, knew that once upon a time it had helped them and might help others, knew that they didn’t want to live in a country where it was every man for himself. They knew.

But as liberalism outlasted its necessity for the majority of Americans, its moral authority waned. From Nixon through Reagan through Bush, Republicans convinced the majority of white Americans that the dispossessed and underprivileged were just another interest group out for themselves, no different than anyone else. They convinced them that liberalism unjustly rewarded the undeserving. And they convinced them that moralism was the same thing as morality – that stern, puritanical proscriptions were substitutes for the kindness that underlay liberal outreach. It was over then. Liberalism was over. America became once again what it had been – a country more interested in punishing than in assisting. Liberals have managed to keep the flame flickering, that old candle burning, but only barely. Now it is so weak it can’t even illuminate a narcissistic demagogue who is both an ignoramus and a bigot.

But while nearly everyone else was abandoning liberalism under the conservative onslaught, the Jews never did – not then, not now. Like African Americans, they held firm.

Nothing, not AIPAC (the American Israel Public Affairs Committee), nor lower taxes, nor attempts to drive wedges between Jews and African Americans, nor the cynically cunning embrace of evangelicals who talk oh-so-lovingly of Israel (because they believe Jews must return to the homeland before Christians can experience the Rapture, in which all Jews will ultimately perish) has persuaded Jews to surrender their liberalism. And in this, those anti-Semites may actually be right. The Jews hold tight not because they gain any great economic or even social dispensation from liberalism, and not even primarily because of that self-protection it provided, but because it was baked into Jewish DNA long before the New Deal – part of Jewish identity. The stereotype of the bleeding heart liberal Jew is entirely accurate. It is practically inseparable from Jewishness.

I suppose all religious groups see their beliefs not just as faith but as sensibilities – scrims through which to view the world. But I don’t think the sensibility is so stark, so powerful, so self-defining in any group more than it is among Jews. I would go even further – perhaps too far. Though debates have raged for centuries over whether Jews are a religion, a race or an ethnicity, I think Jewishness – as opposed to Judaism, which is a religion – is itself a sensibility. Jews are Jews because of that sensibility, which is only tangentially connected to religion and now largely detached from it. As much of an apostasy as it may be to say it, I know religious Jews who don’t have a Jewish sensibility, and therefore don’t really seem to be Jews to me. (Of course, I am absolutely certain that I, a nonpracticing Jew, don’t really seem like a Jew to them.) A lot of the Orthodox, who, not incidentally, are likely to be political conservatives, just seem to be evangelicals with peyes – people for whom dogma surmounts all and on whom the great joys of Jewish-American culture born of that sensibility are lost, especially the deep feeling for others, traditional tzedakah notwithstanding. That is charity, not sensibility.

I think it is impossible to say whether the sensibility was a product of thousands of years of Jewish history and persecution or Jewish history a product of the sensibility. Here is what I do know: The Jewish sensibility is a complex cosmology. It is dark, pessimistic, entirely fatalistic, tragic, believing the worst in people (with good reason!), but also funny, tolerant, generous, forbearing, and, above all, good, hoping for the best in people. I always imagined that it evolved from those persecutions, but also from the fact that while Christians believed the Messiah had already come and promised deliverance, thus providing a gentile happy ending, Jews have continued to wait, becoming increasingly skeptical that He would ever arrive, which also meant that Jews would never receive salvation. Or put another way, Jews live with the active consciousness that there isn’t likely to be a happy ending for them – only a lifetime waiting room. They are sentenced to limbo, so they had better devise ways to deal with it.

What does any of this have to do with liberalism? Just this: Liberalism is one of those mechanisms, along with comedy and art and philosophy and a whole lot of other things, that enables us Jews to deal with the unsparing world and provide us the gratification that we need to soldier on. Most of us avoid talking about Jewish exceptionalism, and, God knows, there have been plenty of morally compromised Jews. But when it comes to politics, Jews truly are exceptional. Far beyond the notion of self-protection, they are liberals because they know in their blood and their bones that it is the right thing to do, because loving and caring for one another are the only things worth living for, and because, if you really want to get religious about it, it is what the Lord doth require of thee. Put simply, Jews are liberals because it is of a piece with how they see the world and with who they are within it. They were liberals before there was liberalism.

Yes, I know, there are prominent Jews on the other side of the liberal-conservative divide, and, truth be told, I have a hard time thinking of them as Jews too. I recall Lillian Hellman’s wonderful analysis of the Hollywood blacklist and the Jewish moguls who instituted it: “It would not have been possible in Russia or Poland, but it was possible here to offer the Cossacks a bowl of chicken soup.” I think a lot of those intellectual Jews who would become neo-conservatives harbored the same fears as those old Hollywood Jews, and they attempted the same appeasement of the Christians. They were just as repelled by so-called instinctive Jewish liberalism as the gentiles were, just as certain that it was un-American and unthinking. Desperate to prove that they were more American than Jew and more intellectual than reflexive, they found that neo-conservatism was their bowl of soup.

For most of us Jews, though, that didn’t cut it. In my own family, no Gabler has ever — ever — voted Republican. No Gabler ever will, since to do so would be self-denial. Moreover, I was brought up to believe that you not only would never think of voting Republican, even for Republican Jews (my own congressman is a Jew who loves Trump), but also that all tolerant, generous and good people – that is, people with a Jewish sensibility — were Jews under the skin. (Hell, I grew up thinking that Adlai Stevenson was a Jew.) There were a lot of Jews out there, just as there were a lot of proto-Nazis, even a few religious-born Jews among them. Growing up, Jewishness meant liberalism to me, whatever one’s religion.

Every so often you read that rank and file Jews are beginning finally to edge rightward. I don’t believe it since it would mean letting go of the Jewish sensibility, which would be a sacrifice not only for Jews but also for America, which has depended on that sensibility as a moral compass. I am certainly not saying that Jews will save the nation in this period of moral disorientation. They couldn’t even save themselves. But I am saying that there is something inextinguishable in us, something decent, something to hold onto, something that will see us through these dreadful times and others to come. Our liberalism is a raft in this stormy, foreboding sea. To have it is a gift. To lose it would be to lose ourselves and now, also, our country.

Neal Gabler’s latest book is “Barbra Streisand: Redefining Beauty, Femininity and Power.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO