Q&A: Martin Stellman, Screenwriter Of ‘Babylon’ And ‘Quadrophenia’

Brinsley Forde as Blue in Franco Rosso’s “Babylon.” Image by Courtesy of Kino Lorber Repertory/Seventy-Seven

The 1980 film “Babylon” is nearly 40 years old, but to American audiences it’s bound to feel fresh. For one thing, the novelty is guaranteed in that the film is only now receiving its theatrical premiere in the United States March 8, but more troublingly the themes of “Babylon,” though filmed a whole ocean away, resonate with the here and now in a way few would have predicted four decades ago.

The movie, directed by Franco Rosso from a script by Rosso and Martin Stellman, is an unflinching look at the reality of Afro-Jamaican youth in Thatcher-era South London. The core group of the film comprises members of Ital Lion, a sound system — a crew of DJs, engineers and emcees that play reggae music in dance halls — on their journey to a fateful blues dance. Throughout the 95-minute runtime the DJ David, known as “Blue,” (Brinsley Forde, the real-life frontman of the band Aswad which provided the film’s soundtrack) and Ital Lion’s other members encounter brutal racial profiling by police and harassment by neighbors and employers.

At the time of its release, the film’s frank treatment of race relations and its extensive use of patois dialogue spelled financial failure, and its salacious “X rating” didn’t help. Though “Babylon” premiered at Cannes and showed at Toronto’s Festival of Festivals, the New York Film Festival passed on it. Vivien Goldman wrote in Time Out that the film was deemed “too controversial, and likely to incite racial violence.”

When the film premiered in Bristol to a primarily young and black crowd, audience members slashed the theater seats as Blue’s anger over prejudicial treatment began to boil over. In the years to follow, “Babylon” became a cult classic, passed around on bootleg VHS tapes between both reggae fans and the demographic whose experience it presented with such acuity: Black English youth.

It’s strange to think that this document all came from a collaboration between two white men: One an Italian immigrant and the other the Jewish son of an immigrant. While Rosso passed away in 2016, his creative partner Martin Stellman is alive and has gone on to work on many more screenplays. He wrote the story for the UN thriller “The Interpreter” (2005) and most recently penned the script to “Yardie” (2018), actor Idris Elba’s directorial debut. Beyond “Babylon” Stellman has another subculture classic to his name in “Quadrophenia” (1979) the film adaptation of The Who’s rock opera album of the same name.

The Forward spoke with Stellman over Skype from his home in Spain about the history of “Babylon,” his second ever feature film.

PJ GRISAR: How does it feel to have the film getting its US release now?

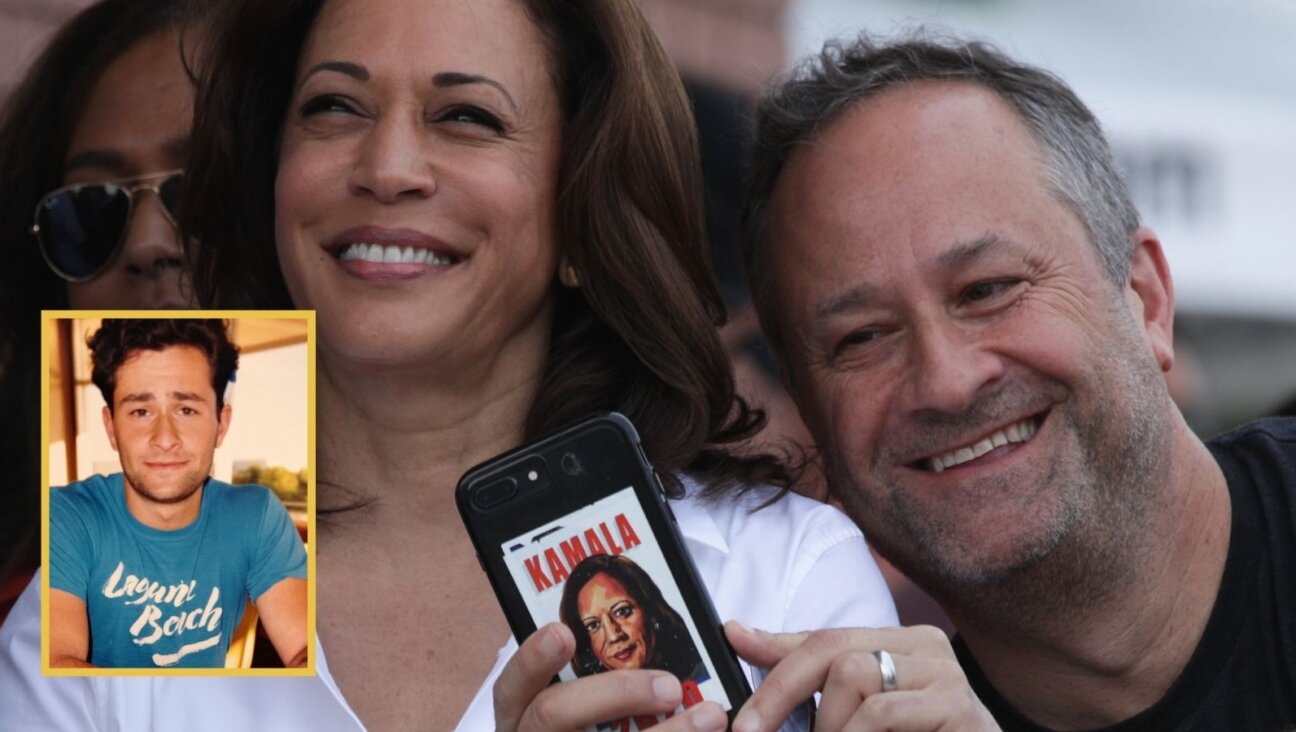

Martin Stellman circa 1975 in his dance hall “Jew-fro” days (L) and now (R). Image by Courtesy of Martin Stellman

MARTIN STELLMAN: It’s weirdly wonderful. 40 years later.

We’re bringing it here at a time when it’s still sadly relevant.

I know. It’s extraordinary.

The film had an interesting journey. I understand it began as a TV play for the BBC that didn’t come together?

That’s not 100% accurate. The late Franco Rosso and I, who had been nurturing it for a number of years in the 1970s, always as a feature film. But we were not succeeding in getting it off the ground. As you can imagine a film with principally a black cast of all unknowns and with this subject matter – all of those things were very much against us getting it made at all really. And then there arose this opportunity for us to do it as a “Play For Today” [a series of televised, often socially aware or plays that ran on the BBC.] That was the slot that controversial or difficult material could pass through the frontier of difficulty. It was going to be directed not by Franco but I think by Franc Roddam who went on to direct “Quadrophenia.” It’s so long ago I can’t remember why it didn’t happen at the BBC. But it didn’t happen there and we just carried on.

But then towards the end of the 1970s you had some bold investors that came through to help make it into a film.

I think very often what happens in movie land is you never get 100% financing and you have to cut corners and make changes to the script. The main savior of the project was the then incarnation of what is now called the UK Film Council. It’s connected with the Ministry of Culture so it’s government money or, if you like, the taxpayers’ money. At the time it was called the National Film Finance Corporation (the NFFC). It was run by a guy named Mamoun Hassan. He was the man in charge at the time and it was sort of happenstance because he was teaching at the National Film School and I had just started there as a student. He had remembered the script that I had submitted in order to get into the film school and grabbed me one day and said, “Whatever happened to that script? I think we could probably finance it.” They provided I think pretty much 80% of the financing.

It was the only thing the N.F.F.C. financed that year.

I wouldn’t know about that. I was too busy working on “Babylon” to be worrying about other people’s problems.

So it all came together and Franco was ultimately tapped to direct. You had both experienced the world of reggae music and the culture of sound systems. How did you both come to it?

We had slightly different experiences. Franco’s was that he lived in South London and his first encounter with sound systems was at the bottom of his garden. Literally. ‘Cause at the bottom of his garden was a church hall frequented over the weekend by sound systems. His first experience was a negative one from what I remember him saying. He had young kids at the time and you can imagine what the bass was like at two in the morning. (Imitates the noise of the bass). Vibrating the windows and his kids’ beds. But because he had primarily up to that point been a documentary filmmaker he had that natural curiosity and I think he got to know a few of the sound system people.

Meanwhile I’m working in the area of Lewisham in southeast London at the northern end as a youth and community worker. I’m 25 and I’m already a huge reggae fanatic. I am running drama workshops and I’m also being introduced to the world of sound systems through them. Back then I was listening to a lot of Roots Reggae and obviously Bob Marley. But this is not that. This is something more. This is cosmic compared to all the music I had been listening to on my very modest stereo system. You go to a blue [a sound system dance] and you’re listening to this stuff not only through these extraordinary sound set ups, but you also have the toasting [often intense talking or chanting by a DJ over an instrumental rhythm] going on. I became a groupie really. Whenever I did my workshops I would say to one of the girls in that group whose brother and friend and other people she knew were involved in sound system “when’s the next blues and can I come?”

I’m guessing you stood out a bit when you went.

I would walk into these extraordinary venues where I would literally be the only white person in a dance hall of maybe 200 people. There was also an element of me just about getting away with being the token white guy because I did have a rather splendid Jew-fro. I could just about in some less skeptical circles get away with being a very light-skinned, mixed race guy.

To that point: The film is very much about being a sort of outsider in a bigoted system. Do you think Franco’s experience as an immigrant and yours as a Jewish kid and the child of deaf parents, one an immigrant, helped you with this material?

Franco was actually much closer to the immigrant experience. I think he came over as a kid whereas my Mom was from a family that had been around the East End of London for at least a couple of generations. My dad, however, arrived in 1934 so he was very much an immigrant. For me, being the hearing child of two deaf parents – more so than the Jewishness I think – made me feel different. I was aware I was in this very strange family where we signed and lip-read to each other. That’s how we spoke and whenever we went out into the street we would communicate like that. And I would feel really defensive about my parents in a public space. In those days, the 1950s and 60s when I was eight, nine, 10 you would get people staring at my parents and I would turn to them and say “what are you looking at?” I was probably a bit intolerant of people’s ignorance of deafness. But to answer your question, I think I felt very much an outsider because of that. I think that gave me a kind of empathy and I think that was certainly true of Franco as well.

Then of course you’re also working with this cast that is enmeshed in the world of sound systems. I wonder if you consulted with them to make sure the patois and everything else was authentic?

Oh God, yeah. (Laughs). Back then the word “appropriation” was not currency, but we were very aware of the issue from day one. There was a great kid named Ali Forbes, who I think is credited for all the help. Ali was first generation. He was born in Jamaica and came over when he was very young and the family had become very good friends of mine and I would grab Ali after we had written a scene and we would check it through with him and he would change it around and correct us and put it in the right patois. And then there was a further process when we were actually filming. Brinsley [Forde] and all the rest of the cast were dealing with the scrip, but Franco and I believed we had to give them as much license as possible to make this story their own. In terms of the material, as much as we had that empathy we were in a sense tourists.

Authenticity was our buzzword and the reason for that is we had a sense tonally and stylistically of the kind of film we wanted to make from day one. The model for us was “Mean Streets” (1973) one of Scorsese’s very early movies. You see a movie like that and you know it was viscerally true to the street and that’s what we kind of wanted to do with “Babylon.”

I read that when you were filming it was a bit tricky because you didn’t want to people to think some of the scenes – particularly those that involve Blue being chased on foot and the cops pursuing him — to be mistaken for the real thing.

There was quite a lot of that. Of course we were shooting in real locations. And we were dealing with real issues. So for example, the scene with the racist family in that — project you would call it over there, we would call it a council estate – you need to be very careful about doing that kind of stuff because there would have been and there were real racists actually living there.

Now that the film’s getting its theatrical release in the states there are added subtitles for some of the British slang. The film of course had subtitles in the UK release for a lot of the patois. Was it always meant to have them?

Yeah. And I think that was a big problem right across the board. Because here’s this British subject matter supposedly in the English language with English actors in it speaking a [kind of] foreign language which is subtitled so it suddenly is turned into what is tantamount to being an Art House European movie and commercially has a very limited market.

Were you surprised by the initial reception of the film? I know it made its way to a cult status later, but it seemed like there was some degree of controversy around the release.

I can remember that there were some sniffy reviews and it seemed to me, though it’s only a vague memory, that there wasn’t very much understanding of it. There was a lot of ignorance of it and I think that this world that we portrayed was so kind of strange and exotic, especially to critics, that some of them found it difficult to relate to. But of course it does actually sit in a much more British tradition of Neo-Social Realism such as movies like Tony Richardson’s “The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner” (1962) and Jack Clayton’s “Room at the Top” (1959) from the previous decade which Franco and I were brought up on. And obviously the work of [director] Ken Loach more recently in relation to the chronology of “Babylon.”

You have had a long career and worked in a number of different worlds. Most recently you worked with Jamaican-British author Victor Headley to adapt his novel “Yardie” for Idris Elba’s directorial debut. There you’re returning a bit to the “Babylon” world actually—

Well that’s a rather sweet story. I actually didn’t work with Victor because at that time there was an existing screenplay that had been written by a guy called Brock Norman Brock and I was brought in at a later stage by Idris. The very reason that I was brought in was because Idris had seen “Babylon” and was a fan and said to his producers “what we really need now is the guy who wrote ‘Babylon.’”

All those years later!

All those years later! I’m actually now going back… there was a screening at the British Film Institute on the south bank of the Thames in 2008 in a new print – the same restoration premiering in New York – and there was this audience that I would say was 75% Afro-Caribbean. And it was celebrated as being this new print, newly remixed music as well and it was extraordinary to see how the film after 30 years held up for me and also the effect that it still had on the audience. And then people came up to me, people who are exactly Idris’ generation and said “this movie was a part of our lives growing up in London and was one of the things that kind of made sense of growing up black in England.” That’s incredibly fulfilling.

“Babylon” opens Friday March 8, at BAM in New York and at the Laemmle Glendale theater in LA on Friday March 15 with more dates across the US scheduled for the spring and summer of 2019.

A message from our editor-in-chief Jodi Rudoren

We're building on 127 years of independent journalism to help you develop deeper connections to what it means to be Jewish today.

With so much at stake for the Jewish people right now — war, rising antisemitism, a high-stakes U.S. presidential election — American Jews depend on the Forward's perspective, integrity and courage.

— Jodi Rudoren, Editor-in-Chief