What all the critics of “Unorthodox” are forgetting

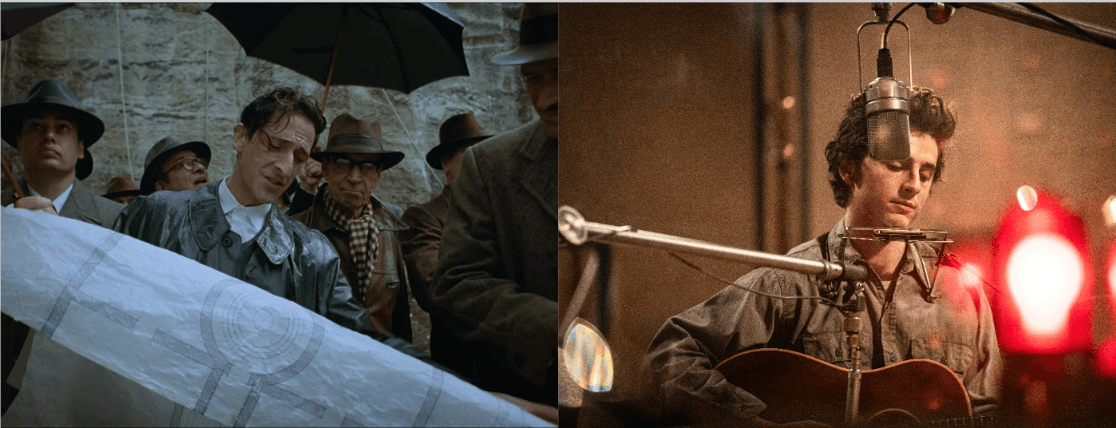

Unorthodox Image by netflix

“Unorthodox” is, if anything, entirely orthodox.

That is to say, the much-viewed and reviewed Netflix offering about a young woman who flees her insular hasidic community follows the typical convention of a number of books and documentaries portraying the ostensibly suffocating lives of hasidim and the quest of some of the braver souls among them to escape into a more wondrous world. There’s a veritable cottage industry of such escapees’ memoirs.

The earliest such narrative, albeit fiction, was probably Chaim Potok’s 1967 novel “The Chosen,” one of whose protagonists is a hasid who breaks from his family and its expectations to pursue a secular profession. Recent years, though, have seen a parade of horribles trotting behind that book (and exhibiting little of its laudable sensitivity).

Hasidic life, as strange, even bizarre in some ways, as it may seem to the average American, is rich and rewarding to the overwhelming majority of the hundreds of thousands who live it. But a straightforward portrayal of a hasidic citizen hardly makes for compelling entertainment. Who, after all, wants to read about a happy family? Such families may not, as Tolstoy asserted at the beginning of Anna Karenina, be all alike. But they are — at least to outsiders — rather boring.

The series has garnered glowing reviews. ABC News commentator Susan Donaldson-James called it “powerful,” and the New York Times’s Marisa Mazria-Katz found it “stirring.” The same paper’s James Poniewozik” described it as “a riveting thriller.” And the Washington Post’s Hank Stuever called the show “gripping and carefully constructed.”

It also has its critical critics. In these pages, Frida Vizel, herself a refugee from an insular Hssidic life, writes that she doesn’t “recognize the Unorthodox world where people are cold, humorless, and obsessed with following the rules.” Though she has been critical of the Hassidic community, she continues, “that doesn’t mean everyone goes about muted, serious, drawn, fulfilling the rules and mentioning the Holocaust.” She found “Unorthodox” to be “dehumanizing.”

Julie Joanes, also here, described the series as “four hours of unabashed bashing of Orthodox Judaism” that “takes practices that have profound spiritual meaning completely out of context, debasing a religion which has stood the test of time for thousands of years.”

To me, though, both those who have celebrated the series and those who lambasted it are missing something. Something important.

Their respective judgments of “Unorthodox,” while useful, perhaps, to the public, ignore something obvious but all the same easily overlooked. Namely, that art and fact are entirely unrelated animals.

Not only is outright fiction not fact, neither are depictions of actual lives and artistic documentaries, whether forged in words, celluloid or electrons. Art can be compelling, beautiful, instructive and enlightening. And when it is any of those things, it deserves praise, at least for its aesthetic qualities. But, at the same time, intelligent assessors of artistic offerings never forget that truth and beauty are not necessarily one and the same. At times they can even diverge profoundly. There is a reason, after all, why the words “artifice” and “artificial” are based on the word “art.”

A brilliant artistic endeavor that has been a mainstay of college film studies courses is a good example. The 1935 film has been described as powerful, even overwhelming, and is cited as a pioneering archetype of the use of striking visuals and compelling narrative. It won a gold medal at the 1935 Venice Biennale and the Grand Prix at the 1937 World Exhibition in Paris. The New York Times’ J. Hoberman not long ago called it “supremely artful.”

And it was. As well as supremely evil, as Mr. Hoberman also explains. The film was Leni Riefenstahl’s “Triumph of the Will” — a fawning but artistically fascinating documentary about the rise of Adolf Hitler. I mean, of course, no real comparison of that film and “Unorthodox.” But recalling the earlier offering is worthwhile, as it reminds us of the truism that art, even impressive art, is one thing, and reality, often, quite another.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism so that we can be prepared for whatever news 2025 brings.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO