Jerry Stiller was so much more than a sitcom star

Jerry Stiller with Anne Meara Image by Getty Images

Gerald Isaac Stiller, adored by millions of sitcom fans as Jerry Stiller, who died on May 11 at age 92, proved that actors are human beings who sometimes must make choices between family and artistry.

Stiller was born in Brooklyn to a family of modest means. His father was a bus driver and his mother a homemaker who had emigrated from Frampol, Poland, a town that appeared in fictionalized form in Isaac Bashevis Singer’s “Gimpel the Fool” and “A Tale of Three Wishes.”

Yet despite Great Depression-era economic woes, when Stiller expressed an early wish to become an actor, he was encouraged with trips to the Henry Street Settlement Playhouse, an arts organization on the Lower East Side that was part of an institution founded by the nurse and humanitarian Lillian Wald, of German Jewish origin.

There as a teenager, Stiller participated in the aftermath of the Federal Theatre Project, a federally funded arts program established under the Works Progress Administration in the 1930s that presented so-called Living Newspapers offering facts about social issues of the day.

As part of the 1943-1944 season, the Settlement offered a show entitled “It’s Up to You,” exhorting audiences to abide by wartime rationing rules. Contemporaneously, Stiller played the title character in a high school farce, “Adolf Hitler Goes to Heaven.”

The combination of earnestness and ludicrousness would pursue Stiller throughout his professional career. Remembered mostly today for shouting imprecations as nightmare elders in TV’s “Seinfeld” and “King of Queens,” which he did with exemplary application for two decades, his talents and experience were far more diverse.

Not that Stiller was ever disdainful about low comedy. As a boy he idolized the vaudevillian Eddie Cantor (born Isidore Itzkowitz; 1892–1964) especially relishing that Cantor was among the few Jewish media stars of the era who made a point of declaring his roots to the public. Stiller and his family kvelled at one of Cantor’s lesser songs, “When I’m the President,” introduced to radio audiences in 1931, mainly because it expressed the notion that a Jewish person might aspire to the presidency, even in jest.

Studying drama at Syracuse University, Stiller was paired in a slapstick comedy duo with Julian Barry (born Barry Mendelsohn) who would later achieve renown as author of the play “Lenny,” about the comedian Lenny Bruce. Yet when he arrived in Manhattan after graduation, Stiller began an series of highly serious theatrical ventures. These small roles gained him little income or fame, but associating in such ambitious repertoire with mighty talents proved an education that kept his spirit vital through years of sitcom fare.

One of his first such experiences was in 1954 at The Phoenix Theatre, a major new off-Broadway establishment, where producer John Houseman staged Shakespeare’s “Coriolanus.” Stiller acted alongside Jack Klugman, Gene Saks, and one of his idols, John Randolph (born Emanuel Hirsch Cohen; 1915–2004).

Soon, on Broadway Stiller was replacing another performer in the role of Crook-Finger Jack as part of a hit production of the Kurt Weill musical “Threepenny Opera.” The cast included Bea Arthur (born Bernice Frankel), Lotte Lenya, Ed Asner, and Jerry Orbach.

Nightly master classes in holding the stage with powerful personalities continued with a 1956 production of Brecht’s “Good Person of Szechwan” starring as various Chinese characters, Uta Hagen, Nancy Marchand, and Zero Mostel. A small role was also filled by Anne Meara, the witty and talented actress whom Stiller would marry and develop a comedy act with, mainly to find a way to work together, since they were almost never cast in the same play or film.

After Brecht, in 1957, Stiller acted two small parts in Shakespeare’s “Measure for Measure” and “Taming of the Shrew” alongside Morris Carnovsky and Norman Lloyd (born Perlmutter)

The following year, he was cast as a character of mixed Spanish and Indian background in an adaptation of Graham Greene’s novel “The Power and the Glory,” as if Stiller were hoping to emulate the career of Eli Wallach, another Jewish actor often expected to play a range of other ethnicities.

Instead, his comedy career with Anne Meara took off, and he would not reappear on Broadway for almost 20 years, until a 1975 comedy by Terrence McNally, “The Ritz.”

Even though his television appearances were heavily weighted to variety and comedy efforts, Stiller remained faithful to his stage origins, appearing in a 1971 TV film of Arthur Miller’s “A Memory of Two Mondays.” The play, evoking the fate of workers in a Brooklyn automobile parts warehouse during the Great Depression, surely struck a chord for Stiller, and his role as a mechanic was akin to the lifelong part played by his father, a frustrated comedian, as bus driver.

Similarly, a working class authenticity imbued one of Stiller’s underrated screen performances, as the transit policeman Lieutenant Rico Patrone in “The Taking of Pelham One Two Three” (1974). This thriller had a screenplay by the American Jewish dramatist Peter Stone, based on a novel by Morton Freedgood, writing under the pen name John Godey.

As Patrone, Stiller’s naturalness and plausibility are such that after two decades of acting, he had clearly arrived at a level of skill whereby he could appear to be a person who had just wandered on camera. His low key drollness played off the always suave theatricality and large-scale comic mugging of his co-star, Walter Matthau.

Stiller could achieve poignancy within comedy, as he did in the role of Artie, an old school screenwriter still chasing development deals in David Rabe’s stage comedy “Hurlyburly,” directed on Broadway in 1984 by Mike Nichols. In a version of Saul Bellow’s “Seize the Day,” (1986) made for television, he was Dr. Tamkin, an apparent con man who claims to be a psychiatrist, poet, and inventor, among other talents.

As this enigmatic and multifaceted character in a cast that included such veteran performers as Joseph Wiseman and Louis Guss, Stiller shone. Even after his run as Frank Costanza in “Seinfeld” began in 1993, he continued to demonstrate that he was first and foremost a stage actor of accomplishment.

As Stewart Lane’s “Jews on Broadway” observes, by the time Stiller was cast as Ivan Chebutykin, a 60-year-old army doctor with comic and tragic facets in Chekhov’s “Three Sisters,” he had acted in 16 Broadway productions over a span of four decades. No matter that a February 1997 issue of New York Magazine, sneered at him as “seemingly a reject from the Yiddish theater.”

Stiller had already proven that for all his accomplishments in sitcoms, his talent far exceeded those boundaries. When given the opportunity on stage or film, he could create lastingly powerful drama that still resonates today. His mishpocheh from Frampol must have been proud indeed, and had Stiller been given the opportunity, he surely would have triumphed in the Yiddish theater as well.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

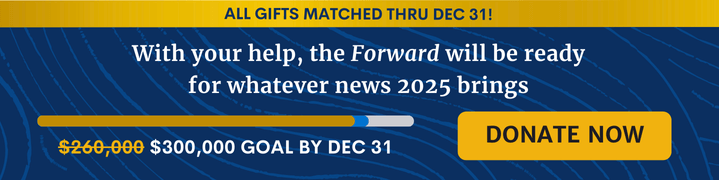

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO