Photo EssayPreparing Jewish bodies for burial, an artist finds inspiration

‘I could have painted landscapes,’ says Karen Benioff Friedman. Instead, she’s portraying the rituals around death.

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Photo EssayPreparing Jewish bodies for burial, an artist finds inspiration

‘I could have painted landscapes,’ says Karen Benioff Friedman. Instead, she’s portraying the rituals around death.

When a Berkeley rabbi in 2004 announced that he wanted to form a chevra kadisha, Hebrew for a group that cares for the dead before burial, an artist in his congregation signed herself up.

Karen Benioff Friedman had a mostly secular upbringing, and hadn’t known much about Jewish burial societies, but she knew she wanted to be a part of one.

“What I found compelling is the idea that we never leave the dead alone,” she said.

1 / 9

Thresholds: Jewish Rituals of Death and Mourning - Placing the Metah into the Casket, 2019, oil on canvas. © 2023 Karen Benioff Friedman. All rights reserved. Photo by Karen Benioff Friedman

Ten years later, while Friedman was studying human anatomy and classical realism at an Oakland art school, she learned of 18th century paintings of Prague’s chevra kadisha. They depicted tahara, the rituals of the burial society.

2 / 9

Thresholds - Jewish Rituals of Death and Mourning - Tying the Avnet, 2023, oil on canvas. © 2023 Karen Benioff Friedman. All rights reserved. Photo by Karen Benioff Friedman

As part of these rituals, bodies are placed in a white shroud before they are lowered into a casket. Coincidentally, Friedman had been painting images of shrouded figures. Seeing the Prague paintings made her think that tahara could be her subject too.

3 / 9

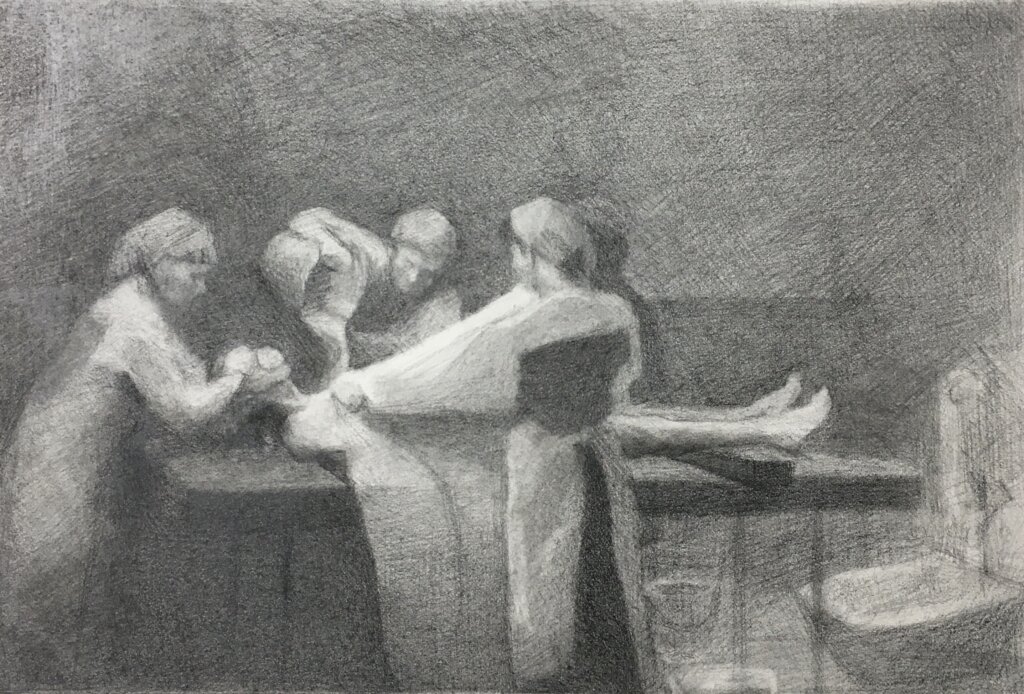

Tahara, 2021, graphite on paper. © 2023 Karen Benioff Friedman. All rights reserved. Photo by Karen Benioff Friedman

“I could have painted landscapes or pets, but this is what really moved me,” said Friedman.

4 / 9

Taharah: Pouring the Second Bucket, 2017, oil on canvas. © 2023 Karen Benioff Friedman. All rights reserved. Photo by Karen Benioff Friedman

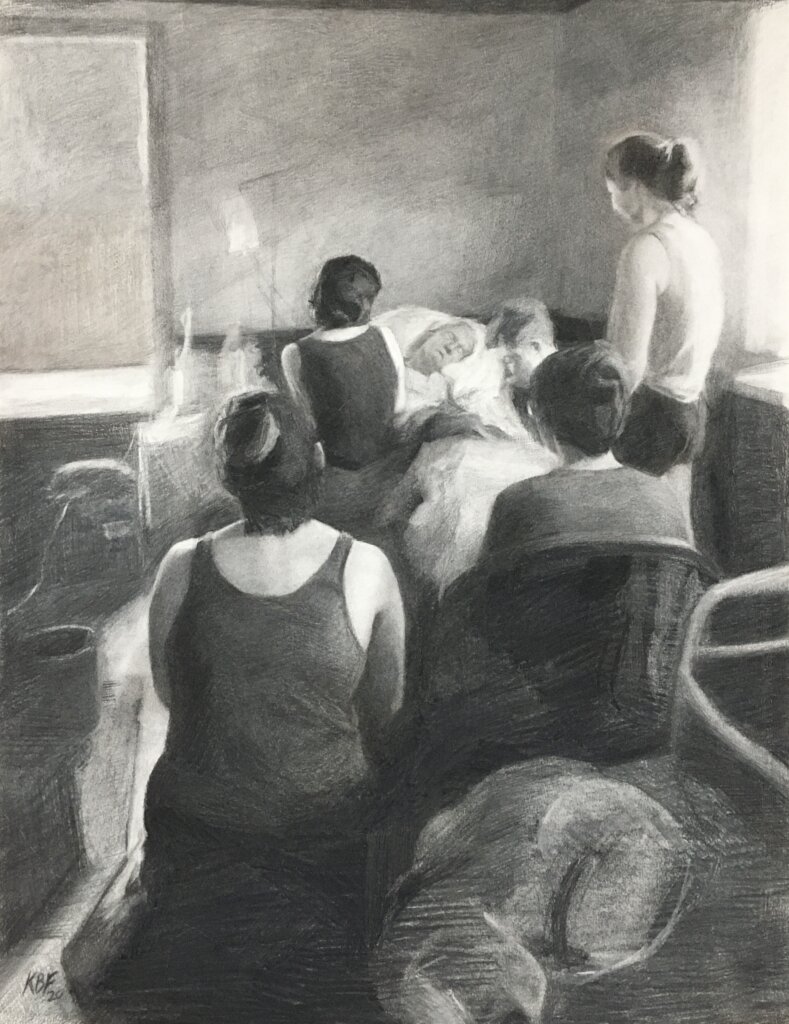

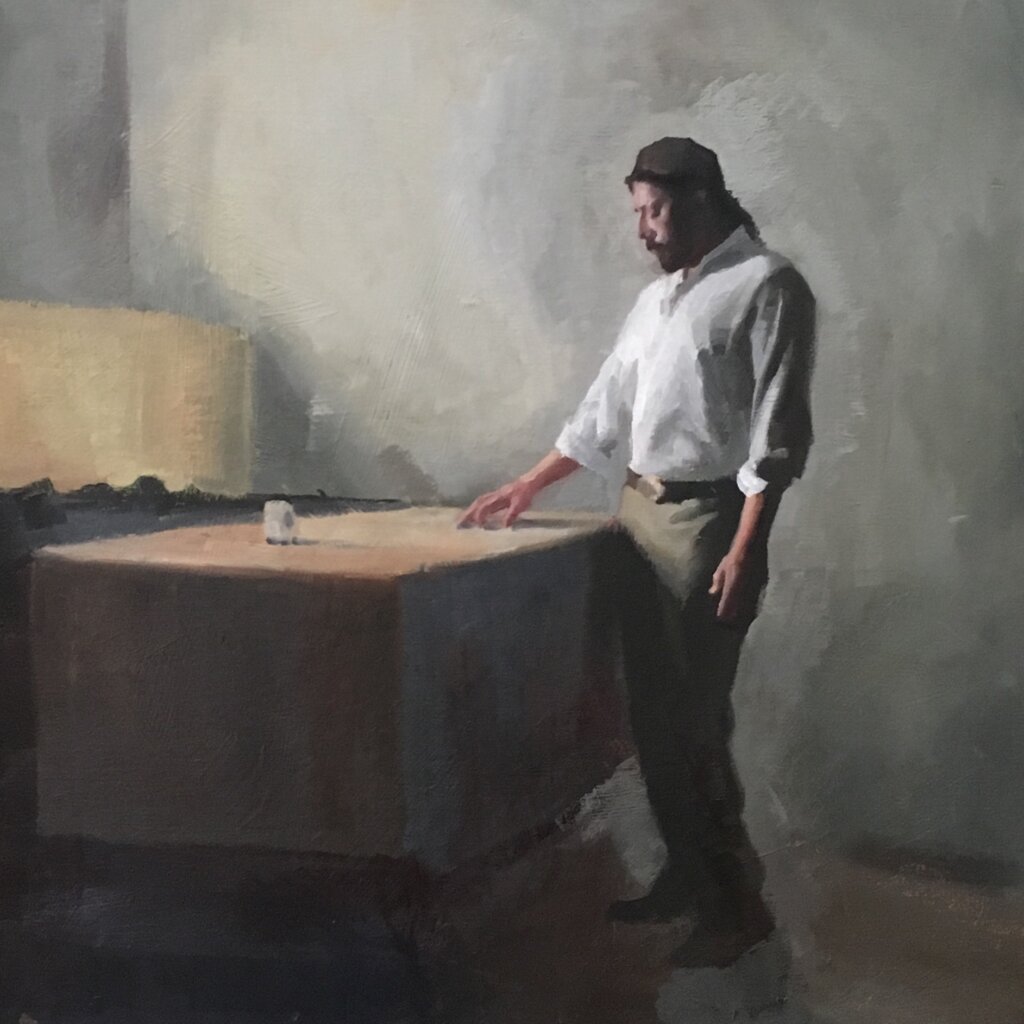

Since then, Friedman, now 59, has drawn, painted and etched more than 150 images of tahara, each a window into a ritual so private that many Jews have little idea what it looks like. Those who perform tahara wash the body, and sit by it through the night, reciting prayers and psalms.

In her paintings, gauzy figures, some enveloped in light, attend lovingly to the dead, cradling their heads and pouring water over their bodies. The mood is somber, despite the daubs of bright blue she often uses for the aprons of the women of the chevra kadisha.

5 / 9

Thresholds, Attending Grandmother's Passing, 2020, charcoal on paper. © 2023 Karen Benioff Friedman. All rights reserved. Photo by Karen Benioff Friedman

Tahara calls for men to care for men and women for women, so Friedman’s subjects are mostly female, because, she said, that is what she knows from her own participation.

Respecting tahara, which means “purification,” Friedman would never try to draw or take photographs of the deceased. But she didn’t work solely from memory either. She hired models to impersonate both the living and the dead. One model did a “pretend tahara while another pretended to be a body that was dressed in a shroud,” she said. She worked from the photographs she took of them.

6 / 9

Angels of Mercy Embrace The Dead, 2019, charcoal on paper. © 2023 Karen Benioff Friedman. All rights reserved. Photo by Karen Benioff Friedman

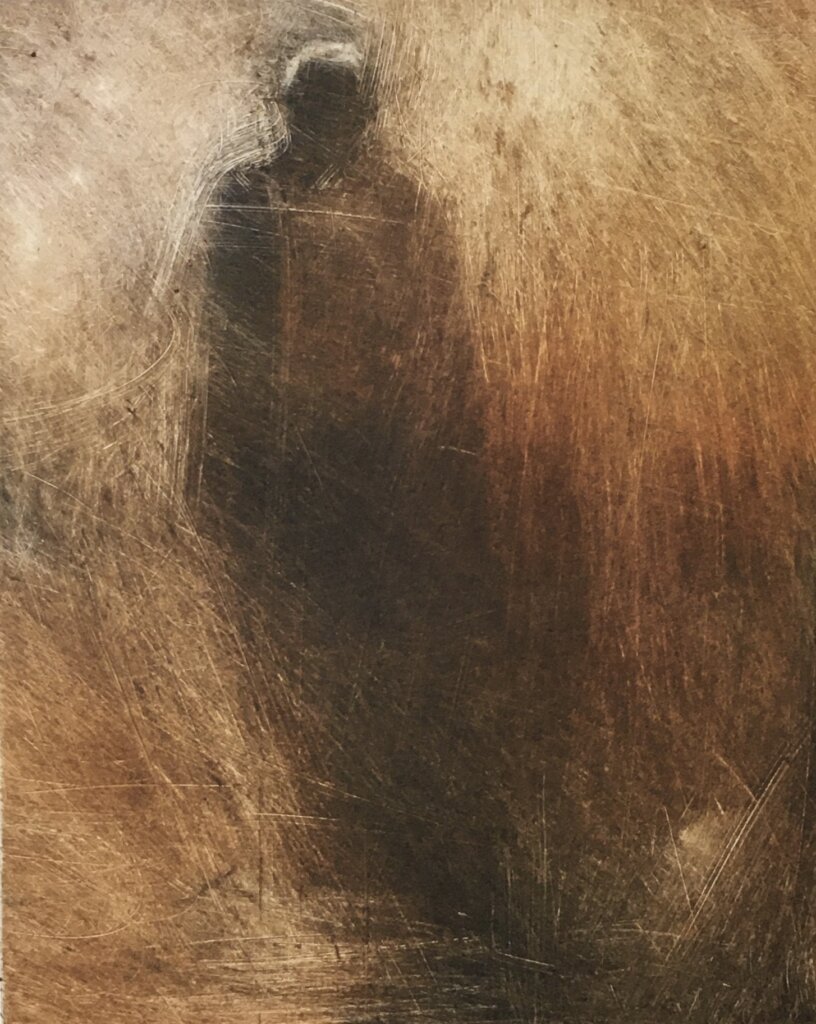

Friedman paints in oils and makes monotypes, a form of printmaking. All her drawings are in charcoal.

Many of her works depict angels. “One of the main pieces of liturgy we talk about is the one about the angels of mercy who embrace the metah — the female body,” Friedman said. “Angels come up a lot, including standing outside the gates of heaven. I love the concept of the angels.”

7 / 9

Angel of Death Holding an Infant, 2022, monotype on silk. © 2023 Karen Benioff Friedman. All rights reserved. Photo by Karen Benioff Friedman

Ultimately, she said, she wants her works to teach about the mostly hidden work of the chevra kadisha, and its commitment to respect the dead, no matter who has died.

8 / 9

Shmira (Guarding the Dead), 2019, oil on canvas. © 2023 Karen Benioff Friedman. All rights reserved. Photo by Karen Benioff Friedman

“We are all equal in death,” she said. “We all wear the same thing and are buried the same.”

9 / 9

A Soul, 2023, monotype. © 2023 Karen Benioff Friedman. All rights reserved. Photo by Karen Benioff Friedman

An exhibit of Friedman’s work will open on Feb. 5 at San Francisco’s Sinai Memorial Chapel and run through March 19.