Photo EssayThrough the eyes of a 102-year-old photographer, memories of a past full of adventure

Al Leff came from a poor, immigrant family in Brooklyn. The U.S. Army and a camera opened up a whole new world for him.

Graphic by Angelie Zaslavsky

Photo EssayThrough the eyes of a 102-year-old photographer, memories of a past full of adventure

Al Leff came from a poor, immigrant family in Brooklyn. The U.S. Army and a camera opened up a whole new world for him.

This isn’t the World War II story you might be expecting. My dad didn’t see combat. Al Leff was a U.S. Army photographer assigned to China, where there were no big battles, at least none that he saw. Just the occasional skirmish. What he did see was a different world from the one he’d known.

He’d come from a desperately poor Jewish immigrant family in Brooklyn, beset at times by violent antisemitism, held down by institutional antisemitism, and the Army and the war were his only way out.

His war stories are never about combat. His experience, he has said, was “part Army, part adventure.” He talks about exotic travel, local curiosities, goofy anecdotes, Chinese warlords and bandits, food (always food), the occasional assault, mortar attack or intel assignment. Occasionally someone gets killed or a bridge gets bombed out. Overall, they are stories of experiences. They’re the stories of a poor Jewish boy, attacked in school by antisemites, a high school dropout with no prospects. And then, thanks to the war, the whole world opened up and he had the adventure of a lifetime.

My dad was able to talk his way into a photographic unit when it arrived in the Army camp in Tennessee where his division was practicing maneuvers. Eventually, the Army shipped his Signal Corps unit overseas to the China-Burma-India Theater.

As his family had struggled in the Depression, a distant relative in the Bronx, Manny Kefig, taught him photography. Manny had turned a walk-in closet into a darkroom and they used his kitchen sink to rinse the photos.

Today, I am sitting beside him at his dining table in his spacious, sunny apartment in Peter Cooper Village. He’s lived alone in the apartment since my mother died in 2016 and it’s just the same as she left it, decorated with her paintings, midcentury wooden furniture and a million interesting tchotchkes.

My dad turned 102 on June 19. He is a man who keeps everything and as a former photographer, he has a large stack of black photo-safe storage boxes. All too aware that he will not be with us forever, I’ve been making audio recordings of his memories before they’re lost to us.

“What’s in the photo boxes?” I ask him.

His voice was once a resonant baritone, but now it’s almost a whisper.

“Pull one over and let’s take a look,” he says.

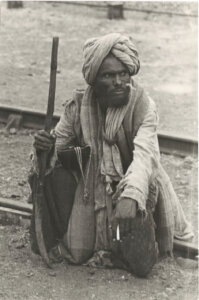

A photo from Mumbai

“I remember taking this one. I thought the man was a beggar but now I notice his clothing isn’t ragged so he must not have been. There were many, many beggars in India,” he tells me. “We shipped out from Newport News, Virginia, to India. We were aboard a former cruise ship that had been taken over by the Army to move troops around the world. The boat was part of the ‘Empress class’ of ships. They were all named the Empress of this place or that Empress of that place.

“Out in the Indian Ocean, the ship made an abrupt and speedy U-turn. Turned out they had been alerted to the possibility of Japanese submarines in the area. The great thing about this ship was she was so fast she could outrun a sub. But after a short while, we got the all-clear and resumed the voyage to Bombay, which was our destination. Now it’s called Mumbai.

“What was very interesting to me in India, the people were very sullen. They were very resentful of the English. Something was starting though. When I was there, there was a movement that Gandhi started of withholding small change so when people bought things they couldn’t get change back. It was a big inconvenience. I saw it later on when we were up in far north India and we could only use rupees to buy things from street vendors — no change. That’s all I saw of Gandhi’s movement but later he would lead the whole nation to free themselves of British rule. It’s incredible, they were able to overthrow the mighty British Empire! Back then, no one could have imagined such a thing.

“I was only a private without even a high school diploma, but I was introduced to what their society was like. I was invited to a British officers’ club, where we ate and played billiards. Billiards was their game. They played billiards and you had to drink. They had a servant dressed in a white turban, white outfit, barefooted, as that was the custom. He would cue up your pool stick for you and hold your cigarette for you.

“There was extreme poverty. At one U.S. Army camp where we GIs were housed, 20 miles outside of Calcutta, the local people would walk to the camp to go through the mess hall trash cans looking for food. There were swarms of people. It became a big problem, to the point where the Army eventually had to put up a fence around the trash cans. There was one woman I saw and she was lying dead on the road to the camp. She must have just laid down to die.

“In the city of Bombay, we had a kind of a ‘tour’ — we weren’t supposed to be in that area. It was the red-light district. The prostitutes were in little rooms with an iron grillwork for a door. They would be standing in the doorway, waiting for customers to come.

“It was a real slum. A very unhappy place. I grew up in slums in New York, during the Depression no less, but I saw something in India I had never seen before — people living in the streets. They didn’t have any possessions. They might have a cup or a plate they’d carry around and they would sleep on the street or in the railway stations. The railway stations were full of people sleeping.”

Dad on the Buzzard

My father is ensconced in his warm red blanket that makes him look like a rosy-cheeked Father Christmas.

“This is me on the Buzzard,” he tells me. “Can you believe that name?”

“What was the Buzzard?” I ask.

“It was a riverboat with a side wheel paddle. You know, like riverboat gamblers? There were so many men who had to be moved around, they had to use whatever kind of boat or train or anything they could get.”

“Where were you?” I ask.

“In India. We went up the Brahmaputra River which is not much known but which is one of the great rivers of India and the world. My buddies and I took pictures of ourselves behind the steering wheel in the little wheelhouse back there. You can see it back there behind me.”

“What do you remember about the trip?”

“We were traveling on the top deck, we GIs, not too many of us. And on the lower deck were Indian families traveling. The lower deck was just barely above the water. And they made little fires and heated up food. Along the shore was jungle most of the way with crocodiles all over the banks sunning themselves. I was plunking at them with my carbine rifle. They would jump. I don’t know if the shot would be fatal but they were certainly wounded.

“So anyway, we went up the river. It was just a day’s journey or so and we landed in a kind of desert where we stayed. It was called the British Rest Camp and it was all sand. The British fed you. And what they fed you was corned beef with sand in it and bread with sand in it and tea, kind of oily on top, with sand in it. There’d be a chow line, you’d walk along with a mess kit and they’d slop food in. And then you’d sit down to eat at a kind of picnic table outside. And when it was mealtime, hawks would arrive. They’d fly in. So many of them, it got dark, and they’d divebomb you to snatch the meat out of your mess kit. There was this poor sucker sitting across from me one time and he was divebombed by a bird that slashed his nose with its claw. It was a very eager bird.”

Over the Himalayas

Now we are looking at several stunning pictures taken out an airplane window.

“The U.S. was in China to support and advise the Chinese on their war against Japan. We weren’t there to fight,“ my father tells me.

The Japanese had occupied large parts of China over the previous six years. The Japanese had bombed out the Burma Road and blocked Chinese ports. The only way to China was in a two-engine propeller plane over the highest mountains in the world.

“We were up in a C-47 transport plane flying over the Himalayas, sitting on our parachutes and we were flying at night. It was my first time in a plane,” he says. “And the Himalayas were all lit up by moonlight. It was a full moon. That was spectacular. We were all awed by that. The pilot deliberately came down lower so we could have a good look at the snowcapped mountains. At one point you could see snow blowing.

“I took some pictures through the plane window. We didn’t have lenses or anything with us. All I had was a camera with one lens, a 50 mm lens. That was it. Seeing the Himalayas by moonlight like that, that was really impressive.

“There was a constant train of planes carrying men and supplies into China. They called it going ‘over the Hump.’

“We were supposed to fly out during the day but there was engine trouble. The planes had two propeller engines and one of ours was not working so they were repairing it all day, which was not encouraging. We were stuck on this sweltering Indian afternoon wearing double uniforms and our parachutes. Double uniforms, because the cabin would be freezing cold up over the Himalayas. By the time we got up in the air it was nighttime.

“The seats were parachute seats along the sides of the plane, like a bench and aluminum frames and a parachute that you were sitting on fitted into the frame. You had to be ready to use your parachute. I read that 500 planes went down in the Himalayas.

“The biggest worry was about landing there alive. I’d heard that the Japanese had put out the information to the local tribes that if they brought in an American or an American head they could have their choice of gold or a watch. I think it must have been true.

“Inside the plane, for oxygen, there was a rubber line along the top frame of the plane like where you would have the overhead bins nowadays and there was a tube that dropped down for each seat and it had a mask that you could hold over your face.

“And the funny thing was there were these two guys on the plane who had brought along animals that they picked up in India. One had a little dog so he was sharing his mask with his dog on and off. He had the dog in his lap. The other one had a monkey and he shared the oxygen with the monkey. Nobody looked when you were getting on the plane to notice the animals. The only thing they knew was everybody had a seat. It was like, ‘As long as the right number of men get on the plane, that’s all that counts. So what if one has a dog and one has a monkey? Not my department.’”

The one about the rat

“This one reminds me of the encounter with the rat,” my dad says. “Do you know that one?”

I do know that one. I’ll let him tell it.

“In Kunming, we GIs stayed in Hostel 11 but we ate at Hostel One across from the airport. Kunming was Army headquarters in southwest China. One of my roommates was Kenneth Ng from Boston. That’s him in the picture and that’s me pretending to buy something from the PX. Ng was a supply sergeant and he worked in the PX. So he had secured a large cardboard cigarette box, you know, that they shipped cigarette cartons in, and we were using it as a trash can for the room. We slept in bunk beds, either two or four to a room, I can’t remember anymore.

“Anyway, I had the bottom bunk. Kenneth had the top bunk. And one night in the darkness, we heard, JUMP-CRASH-SCURRY-SCURRY-SCURRY-SCURRY over and over again. So I got out my flashlight and I shined it in the direction of the noise and we saw a massive rat sitting on the rim of the box. It had been jumping in and out getting little bits of food that we’d thrown out I guess. Click! I switched the light off right away and I said, ‘Ng, when I say ‘go,’ shine your flashlight and spotlight the rat and I’ll try to hit him with my boot.`

“So I found my boot in the darkness and got ready. It was a big heavy Army boot. ‘OK, go!’ and Kenneth flipped on his flashlight, and there was the culprit right in its beam. I shot my boot at the rat and click! Kenneth switched the light off right away. And I guess my aim was good because for the next half-hour in the dark we heard thrashing on the floor. Then it stopped.

“By the light of day, we saw the results, blood, fur and teeth all over the floor. Disgusting, perhaps, but the plan worked.”

Hundred Victories Wei

This photo shows a Chinese army commander surrounded by staff. On the back of the photo, my father’s scrawl says “Marshal Wei.”

“Wei Lihuang. He was a party guy,” my father says with a gleam in his eye. “I met him down near Paoshan in the Yunnan Mountains.”

My dad always said Wei was a warlord but it turns out he was a general and a very successful one at that, nicknamed “Hundred Victories Wei.”

“Do you know who’s in the picture with him?” I ask.

“I wouldn’t know who they were,” he says. “No. My point of view was like an earthworm’s view of the war. The bigger picture was not visible to me. What I knew is while we were stationed there, Wei Lihuang wined and dined us. If you were an American GI, it didn’t matter what rank, you were big.”

Wei threw elaborate Chinese banquets for the GIs, my dad tells me, they went on for hours and featured many, many courses.

“They always finished with a bowl of fish and chicken heads for dessert,” he says. “Really, that was a delicacy. You would nibble on the cockscomb. Well, not me. I wouldn’t touch it.

“There was a lot of heavy drinking from these small china cups called ‘gam-bei’ cups. ‘Gam-bei’ means ‘dry bottom’ so you can imagine the custom. There was a gam-bei between every course. A serving boy would fill the men’s cups and we would take a gam-bei. Bottoms up! — and then hold the cups upside down to prove the cup had a dry bottom. Men were blind drunk. I was paralyzed.

“There was a mud wall that surrounded the compound and you’d go out and pee against the wall. At one point I went outside to pee and I was standing next to a Russian colonel who was engaged in the same activity. Suddenly, the Russian said,”— my father makes his voice deep and gravely and puts on an accent — “‘You are peeing on mine overcoat.’ He might have been the only Russian I ever saw, even though we were allies. It was mostly Americans and Chinese.”

Lady Mountbatten, Part I

My father’s memories of Lady Mounbatten have always featured heavily in his story rotation. He was assigned to photograph her as she toured the Burma Road construction in southwest China, It was one of his prize assignments. She was a famous figure at the time. He takes the first of these photos.

”There she is with the Burma Road construction,” he says. “You can see the pile of gravel and the switchbacks behind her. This part of the Burma Road in China, the Allies were building from scratch. The Japanese had bombed the section in Burma to pieces and the Allies were rebuilding that section separately.”

Lady Mountbatten, Part II

“The other photo is with Chinese officers presenting Lady Mountbatten with a samurai sword that must have been taken off a dead Japanese soldier,” he says. “I have a few scattered memories from my time with her. She was traveling in a motorcade with Jeeps down near Burma. She was seated in a Jeep and I was seated with her at one time and we chatted some. She was an impressive person — wise, really well-informed, educated, intelligent, good-looking. When I was riding in the Jeep with her she was pointing out the hills, saying ‘I think there’s magnesium in that hill’ or some kind of ore. I was very impressed. I hadn’t even finished high school. I didn’t know anything like that.”

When I looked up Lady Mountbatten, I was surprised to see that her grandfather was a Jew. Apparently she was badly bullied in her exclusive boarding schools for it. It made me wonder if she felt more comfortable with my father because of the shared background.

Epilogue

“When I came back home after the war,” my father told me. “I opened a small photography studio back in New York and I had a sign in the window that said ‘Personal Photographer to Lady Mountbatten.’ I made the most of it.”

And he did.

Back in New York after the war, he opened his photography studio, got his GED, then his bachelor’s and master’s degrees on the GI Bill. He met my mom in an NYU class and wooed her with tales of his adventures. They lived a long, happy, free-spirited life together. My dad became a school librarian and a man of knowledge who delighted his students with many stories. The war opened up a new and unexpected world to him.