Remembering Gella Schweid-Fishman — a Yiddish teacher we teen girls could relate to

The other teachers, all male, had fled Europe, and their accents and bearing bespoke ‘old country’

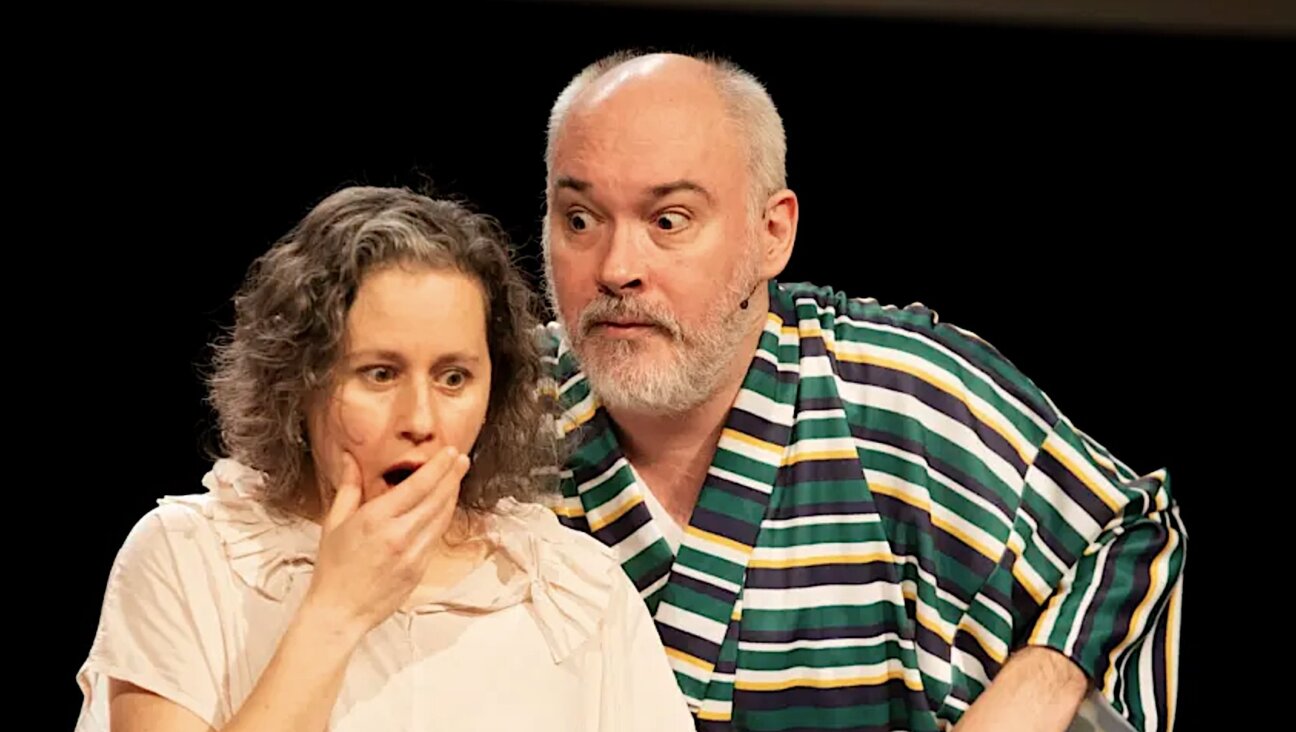

Courtesy of Courtesy of The Sociology of Language and Religion

This month marks the yortsayt of Gella Schweid Fishman. She was a Yiddish teacher, archivist, poet and, together with her late husband (the sociolinguist Dr. Joshua Fishman), a fierce advocate for the language they loved. As my teacher, she tried hard to pass some of that love and reverence over to me.

I first became her student in the fall of 1964. I had just graduated from the Sholem Aleichem Folkshule #14, a Yiddish elementary school in the Kingsbridge section of the Bronx which met three afternoons a week after public school. I had signed on to go to mitlshule (Yiddish high school) which met on Sundays and was a long subway ride from my home in the Bronx. But I didn’t care because I’d had such a rich experience in elementar shule that I wanted to continue. To me, the Yiddish songs and stories were more vivid and dramatic than the American ones we learned at P.S. 95.

So starting that September, my friend Barbara and I met Manny and Ira, two boys from another part of the Bronx, and we all traveled together on the subway ride to mitlshule. It was thrilling for me, who had no brothers or guy friends, to cavort with two real live boys all the way to 14th Street. I was particularly taken with Manny, a gregarious and confident guy. And Gella was Manny’s mother.

She was one of my literature teachers at mitlshule. The other teachers – Khaver Vladkofsky, Khaver Olitzky and Khaver Borovic (Khaver is a Yiddish word for Mr.) – had all fled Europe, and their accents and bearing bespoke ‘old country’. By contrast, Gella not only had a perfect American accent, she was also slim, blonde, and wore stylish skirts and blouses. Decades later, she expressed to me her feelings of being an outsider because she was American-born. But at the time, what we saw was a thin, pretty woman enamored of Yiddish poetry.

She was so devoted to us that one year she picked Barbara and me up and drove us door to door to mitlshule. I gave that up after a while because I wanted to take the train with Manny. But I remember that during the time Gella drove us to mitlshule she often wore fishnet stockings, which were in style then. Even my mother, who was fairly Bohemian, didn’t wear fishnet tights.

Once, I got to see their house. Gella invited my family and me for a Shabbes meal at their house on Bainbridge Avenue. Naturally I was thrilled to spend an evening with my adolescent heartthrob, but I don’t remember the socializing as much as the evening’s length: there were what seemed like endless poems recited, rituals enacted and unfamiliar Shabbes songs, all in Yiddish. My parents were proud cultural Jews but wary of religion. I have a memory of them chafing under all that enforced yidishkeyt.

After four years of mitlshule, I went on to college in the midwest; then – graduate school in London. I eventually settled in Providence, RI with my husband and two children, having long ago lost touch with the Fishmans. I did end up running a basic Yiddish class at the local JCC where I was always one step ahead of the other students as we worked our way through Sheva Zucker’s “An Introduction to Yiddish, Volumes 1 and 2”. I could muster a fairly decent accent. But my vocabulary and reading skills were adolescent at best.

When our younger daughter graduated college, my husband surprised me by announcing that he wanted his turn to live in New York City. The fact that we were in our late fifties with no job prospects did not deter him.

So in the summer of 2011 we moved to Manhattan. My husband, luckily, found a job that would support us. As we settled in, I realized that this was the city where I could learn more Yiddish than I knew how to teach. And my first step in that direction was to contact Gella.

By this time I had heard that she and her ailing husband had moved from the house where my family spent that long Shabbes dinner to an apartment in Riverdale. Their phone number was still the same, and my hand shook slightly as I dialed the 718 exchange. It had been more than 30 years since we last spoke. But the voice at the other end of the receiver sounded strong, curious and delighted to hear from a former student.

Several days later, I stood facing a colorful Armenian tile that seemed perfectly appropriate for the entrance to the Fishman home. When Gella answered the door, it took me just seconds to reconcile the memory of her with the older woman standing before me, because she was so much the same. She was still blonde, on the slim side, wearing a pretty blouse and garnet beads. Her gait was a little slower but her will seemed strong and her mind sharp.

“Kumt arayn, Marele/Come in, Mara dear,” she motioned, ushering me into a spacious living room, lined with books and pretty objects. “Zets zikh avek./Have a seat.”

She addressed me only in Yiddish, and I struggled to keep up for the next four hours. I don’t remember what we talked about, but I do recall leaving that first visit with a headache from trying to maintain a conversation (and such a long one!) in a semi-forgotten tongue.

Soon after, I enrolled in a weekly Yiddish class at the Workmen’s Circle. As my listening and speaking skills improved, it was less tiring to spend hours in her living room with minimal English, and I appreciated the depth of our conversations.

When I’d first encountered Gella, I was an adolescent with youthful yearnings. Now we were on a more level playing field. She’d had a long-term marriage and so had I. She had raised three sons and I – two daughters. She was curious to know how I’d met my husband and she told me in detail (and in Yiddish) about sitting on a park bench years ago with this highly intelligent young man and realizing, though the words were not yet spoken, that they were heading toward a long-standing union. By contrast, I told her about my hesitation at the start of my marriage and how good therapy helped me settle into the deep connection that had been there all along.

It was fun doing ‘girl talk’ with someone my mother’s age. She asked me sharp questions about my husband, my girls and our continuing Jewish journey. She wanted to know about my work – the Alexander Technique – which was hard enough to explain in English.

I listened to childhood stories of Manny. I listened to all her sons’ struggles for love and happiness as they navigated adulthood.

My late father, like Gella’s husband, was an intellectual who enjoyed an audience and I saw similarities in how both wives protected and bolstered their husbands’ well-being. Gella had moved to several far-away cities for her husband’s career and over tea she expressed both the strain and the excitement of moving. I knew she’d always been an ardent admirer and helpmate to her husband, but I guessed that time and the Women’s Movement had some sway, because when she showed me a book of her poetry, her maiden name was now added to her married name.

From time to time she picked up the book and read me some of her poems. One was based on a photograph of her and her youngest granddaughter holding hands as they twirled on the living room floor.

“I have to dance with you now,” the poem said in English translation, “Because I won’t be here to dance at your wedding.”

She’d told me, more than once, about some serious health issues that were being kept at bay. Ever the dedicated archivist, she showed me a large folder with details about her prospective funeral; who she wanted to speak and in what order. I was both inspired and taken aback by her matter-of-fact manner.

Every two or three months after that, I took the bus to Riverdale, savoring the trees and quiet of her neighborhood. Several years into our visits, Gella fell over some construction in her hallway, broke a hip, and needed a walker. Now when I knocked on the door it was often a five-minute wait until she answered the door.

But her mind was still an ayzernem kop/an iron mind. It felt like she was often looking back over her life and trying to get at some truth that was dangling just out of reach. It seemed she was questioning something about her role as helpmate and her own unspoken needs and how the world had changed regarding a woman’s place in it. She wondered about all that she’d done willingly as well as all she’d done because she had no choice. Coming from a different era and a more equitable marriage, I was fascinated by her inner struggle.

On what turned out to be our second to last visit, she brought out her funeral folder and told me that the one speaker she still needed was a former student. Would I be that student? I said I’d be honored. And, of course, she reminded me, I‘d need to give that talk in Yiddish.

I hesitated, panicked for an instant, and then nodded yes.

Several months later, when I heard a soft-spoken voice on the phone saying he was Gella Fishman’s rabbi, I knew what it meant.

Mustering all my language skills and warm feelings for Gella, I wrote out my first eulogy. I was sure there would be many Yiddishists in the sanctuary who would be horrified at my grammatical errors. Gella’s sons, who had heard and spoken a flawless Yiddish from childhood, would be speaking before me. But I was there as Gella’s student and my job would be to give a picture of her as I saw her.

I was shaking on my way up to the lecturn. With limited vocabulary, I tried to give a sense of Gella’s graciousness, her intellectual curiosity and her devotion to Yiddish. When I mentioned my surprise at her fishnet stockings, several people in the sanctuary laughed or nodded in agreement.

Gella was a superb role model on how to age with dignity and passion. If I’m lucky, I’ll wear garnet beads too and be curious about the world just as she was. I hope she’ll forgive me for doing most of this in English.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO