A time when Tbilisi, Georgia, had a rich Yiddish cultural life

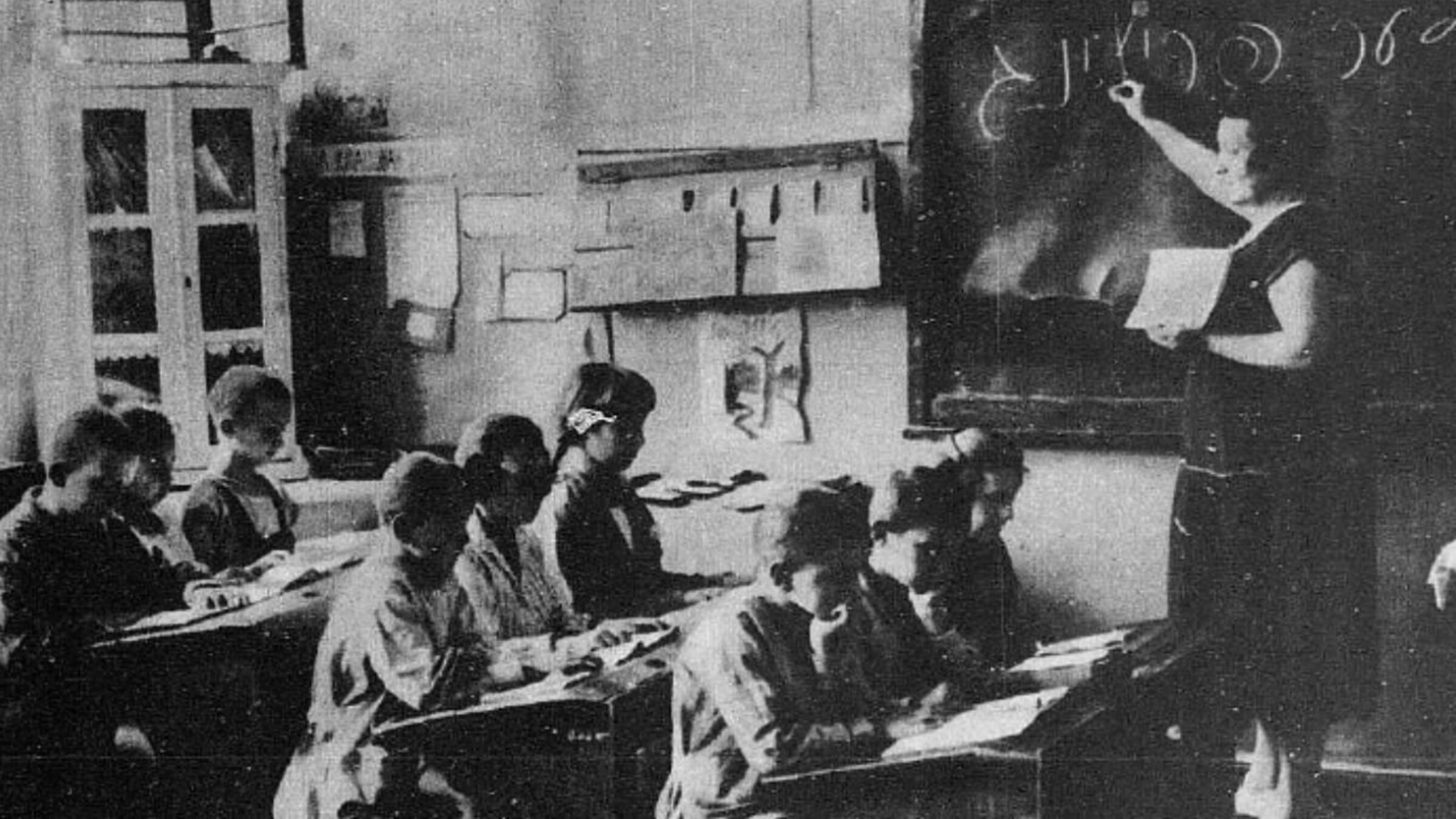

A Yiddish school in Tbilisi, published in 1928. The city is referred to here by its Russian name, Tiflis Photo by the Forward

“Yiddish is a language of our memory and migration trails.”

So said 72-year old Elena Schechter, a lifelong resident of the city of Tbilisi, Georgia, during a recent interview with the Forverts.

Schechter’s father had fled Moldova in the early 1930s and found Georgia to be a place where he could be openly proud of his Jewish heritage. During the era of the USSR, Jews in Georgia were allowed to study Hebrew and Yiddish, while many others across the Soviet Union were prohibited from doing so. Georgia had its own Ashkenazi synagogue, along with a theater staging performances in the Yiddish language.

These days, Georgia’s Ashkenazi Jewish community is almost gone. The vast majority of Schechter’s relatives and friends of Jewish origin migrated to Israel in the 1970s and 1990s, while she and her immediate family remained. What’s left is only a small group of elderly people as well as some teenagers living with their grandparents, waiting to graduate from high school and join their parents who already reside in Israel or elsewhere.

“Sometimes, I like to joke that if Georgians treated us badly, I would have had more courage and reasons to make aliyah, but I actually feel accepted and welcome in our country,” Elena said.

Many of the Jewish families in Georgia today, including my own neighbors – the Feldmanns, the Silvermans, the Rozenbaums and the Shapiros – have been there for generations, starting from the early 19th century, having migrated there from Eastern Europe, often as a result of pogroms. One could visualize this tiny European city with a Jewish quarter located near the market square, and homes where Jewish families secretly kept their belongings wrapped in a carpet, ready to escape in case another pogrom hit.

Today the Ashkenazi Synagogue is a Sephardi house of worship and is located in the city’s center. Nearby, in the Museum of History of Jews in Georgia and Jewish-Georgian Relations, the ceiling now has stainless glass skylights depicting a star of David, designed to resemble a synagogue. Both religious and secular artifacts on display have been carefully selected or received as donations from people eager to promote a Jewish museum in a country that has demonstrated tolerance and acceptance towards the Georgia’s Jewish community throughout its history.

The museum contains a number of Yiddish books and other artifacts dated between 1896 and 1921, many of which were sent from East European cities like Zhytomyr, Ukraine. In Tbilisi those books, which include Sholem Aleichem’s stories, were once used in the Yiddish public schools.

Many descendants of Georgia’s Jews, now living in Israel, the United States, Canada and Russia, regularly send the Georgian Jewish community money to ensure that the local Ashkenazi Jewish cemetery is well-preserved, organized and monitored. As a result, the cemetery is in very good condition. Tombstones are made of expensive stone materials and their engravings in old Russian, Russian, Hebrew and Yiddish are easily readable.

Among the people buried in the Ashkenazi cemetery of Tbilisi are the late Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon’s maternal grandmother, Slava Schneerova, and Sharon’s cousin. In fact, Sharon’s parents both lived in Tbilisi and made aliyah together in 1922, leaving their immediate family in Georgia.

Today Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University offers courses in Jewish studies. The Jewish community has several courses in the Hebrew language, sponsored by organizations like the Jewish Agency, but there are no Yiddish classes, making it difficult to imagine that in the early 20th century the city had a vibrant Yiddish-speaking community.

In 1897, the Yiddish-speaking community of Tbilisi had 3,668 members. Most families sent their children to Yiddish-speaking schools, raising concern among the Communist-run state schools. The situation was reported in the Chicago-based newspaper “The Sentinel” on July 28, 1922, referring to Tbilisi by its Russian name, Tiflis: “To prevent the Yiddishizing of the public schools of Tiflis, the commissary of education of that place ruled that Yiddish shall not be the language of instruction in schools having a majority of pupils.” The article went on to explain, however, that Georgian officials did agree that “the majority of Jewish children acquire a knowledge of Yiddish before they learn Russian.”

Hana Fidelman, a native of Binyamina, Israel, which was once inhabited by a sizable community of Jews from Tbilisi, said that her mother, Phina Khananashvili, was born into a family of religious Georgian Jews and was herself educated at a Yiddish school in Tbilisi, because those were the only Jewish schools that admitted girls. The more traditional Jewish schools taught only boys.

In an article published by the Jewish Post on Nov. 9, 1961, author Barbara Schwartz describes her discovery of Yiddish-speaking Georgian Jewish men at a Sephardi synagogue in Jerusalem. “There we were greeted by two spry old men who spoke enough Yiddish to show us around and answer our questions. This was the Sephardic shul, they apologized, and so their Yiddish was not as good as it might be. What they lacked in linguistic proficiency, however, they more than made up in charm.”

Jan Peerce (1904-1984), the first American singer to visit the Soviet Union on a concert tour in 1956, had his own Yiddish moment during his stay in Tbilisi. At a press conference he gave in Tel Aviv after returning from his trip, he said that he had entered a synagogue there in order to join the service and asked the gabbai running the minyan if he could lead the praying. The Sephardi gabbai looked him in the eye and asked in Yiddish: “Do you know what you have to do?”