A story about a Sukkah on the Argentine grasslands

A farmer describes what Sukkos was like for his family when they immigrated from Russia and didn’t even have a house yet.

Screenshot Courtesy of Miriam Udel

[This story, translated from the Yiddish by Miriam Udel, is the third in a series of Yiddish holiday tales for children that will run throughout the Jewish year 5785. Udel prefaces each story with an introduction to provide useful context for the reader.]

Depending on where you live, the sukkah is almost always too cold, too hot, too rainy or too windy. We love it, though, despite and perhaps also because of these discomforts. Dwelling in it reminds us of how the Israelites lived in tents throughout 40 years of wandering in the desert. When a sharp gust of wind blows and we feel the sukkah’s vulnerability, we also confront our own. The holiday evokes this delicate balance, which has lasted throughout Jewish history, between feeling safe and protected on the one hand and feeling precarious and uncertain on the other.

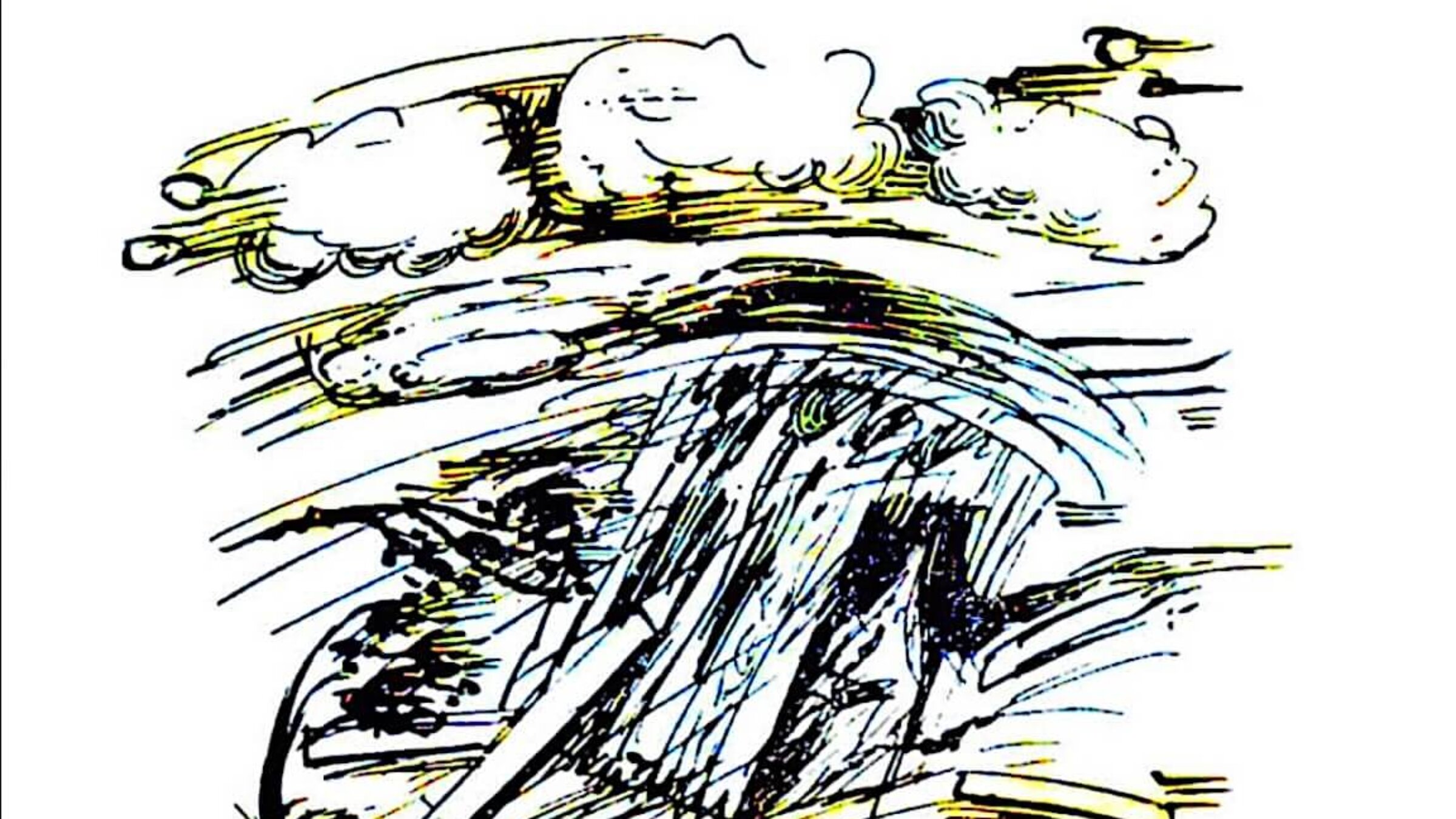

The breeze on Sukkos is delightful. It can rustle fabric “walls” and make sparkly decorations twinkle in the sunlight. But what happens to our holiday rejoicing when the wind blows at gale force, and our symbolic home can’t withstand the assault? During the Grace After Meals on Sukkos, we implore God to restore “the fallen sukkah of David,” a phrase that refers not only to the restoration of King David’s line but more broadly, to the healing of Jewish suffering. A fallen sukkah is an image of sorrow and loss.

This year we find ourselves in particular need of steadying and mending. Americans throughout Florida and Georgia have had their permanent homes ravaged by wind and water damage with the recent, severe back-to-back hurricanes that are letting us know that climate change is already here.

And the Jewish “Big Tent” has been devastated by a year of misery and bloodshed, exacerbated by our own political disagreements about how to move forward as Jews and human beings. This most joyful of holidays — about which the Torah says, “You shall surely rejoice!” — bears the shadow of “just before,” as this week marks what now feels like the horrors of last year’s Simchat Torah in Israel. The windblown sukkah helps us to picture danger and resilience.

“A Sukkah on the Pampa,” one of the holiday tales collected in Zina Rabinowitz’s 1958 collection Der liber yontef (“The Precious Holidays”), dramatizes the challenges confronting a family of Jewish agricultural colonists in the pampas, or grasslands, of central Argentina and the storm that destroys their first sukkah. They learn to build differently to suit their environment — partnering with God, as it were, to solve the problem.

Starting in the late 1880s, Argentina’s vast plains became the destination for tens of thousands of Russian and Polish Jews fleeing antisemitic violence and seeking stability for their families. Baron Maurice de Hirsch, a German Jewish industrialist who made a fortune building railroads, purchased immense tracts of land in the Americas with the purpose of safely resettling Jews and incentivizing them to become farmers. His Jewish Colonization Association helped fund the costs of travel, farm equipment, and training for Jewish immigrants to Argentina until the mid-20th century.

Today we might raise questions about the story’s imagery of “conquering” the land, especially given that the Jewish colonization experiment played out against the backdrop of the Argentine government’s recent land seizure from indigenous peoples and a subsequent campaign to populate the pampas and Patagonia with settlers of European descent. But the real triumph for the first-person narrator is not conquest but endurance. Having devised a defense against the ambient winds, he delights in telling his grandchildren about the perilous first Sukkot during which their parents were nearly blown away. In doing so, he equips them to persevere.

‘A Sukkah on the Argentine grasslands’

By Zina Rabinowitz

We were sitting and chatting with the old Argentine farmer in his dining room. Suddenly, our host extended his hand and pulled a string we hadn’t even noticed before. The thick ceiling suddenly opened right up, and we found ourselves gazing up into a clear blue sky.

“There’s no other sukkah like it!” smiled the old man, seeing my amazement, “And not only in all of Argentina. I’m sure that you won’t find such a wonder as my sukkah anywhere else. Whenever you choose, it becomes a large, sturdy dining room! Or if you prefer, it becomes a sukkah with an open roof, which I can cover with green cuttings! Surely you’d like to know why I’ve built such a strong sukkah? Well, I’m about to tell you!

“We came to Argentina from what used to be Russia. I wanted to live in a free country. I wanted to become a colonist, making a living from farming. So I bought some land right here on the pampa, where there was nothing to see at all, other than a field overrun with thorns and grazing for cattle.

“When we arrived on the Argentine pampa, it was high summer according to the Russian calendar. But here on the pampa, it was winter. The winds howled like wild animals day and night. We were strangers in this country, greenies on the pampa. We were novice farmers. Our cattle ran wild: they wouldn’t allow themselves to be milked, and they had to be restrained and held firmly in place at milking time. They would attack us by kicking, and not infrequently, they’d knock over both the people and the pails in which we were trying to collect a little of their milk. We suffered plenty on their account. Don’t even ask.

“But even worse than the wild cattle was the winter. We didn’t have a house, so we dug out a pit and used it for cooking, sleeping, and praying to God that the winter departs as quickly as possible and spring arrives. But the winter wasn’t in any hurry to leave.

“By the eve of Sukkos, it was just the slightest bit warmer. So I said to my wife, ‘Since God has helped us to survive this hard winter, I want to put up a sukkah and celebrate the first Sukkes here as it says in our Torah.’

“So I pounded four rods into the ground and erected four walls that were also made of rods that I had glued together all along their length and breadth, and on top, I laid down more rods this way and that. We don’t lack for green cuttings for the roof on the pampa. My wife dragged out the best of our rugs and blankets from the dugout, ones we’d brought with us. We hung these on the inside walls so that it looked like a cozy sukkah. That day leading into Sukkos was warm and quiet, and the plant cuttings lay peacefully on the roof.

“As we sat down to the meal with our two boys, there wasn’t the slightest bit of wind in the air. I picked up a glass of wine to recite kiddush, and I said to my sons: ‘Just as the Jews lived in booths when they left Egypt, so too do we sit now in the sukkah. Let’s hope that a year from now, when the precious holiday of Sukkos comes again, we’ll be living in a proper house. But in any event, we’re celebrating this year’s holiday in a sukkah.’

“Before I could even get through the kiddush, we heard some kind of whistle pierce the greenery atop sukkah. First one whistle, then a second, and suddenly, the cuttings disappeared from the roof. And then we heard another whistle, a much stronger one, and the pampa wind tore down all the rugs and blankets from the walls.And it seemed as if any moment, the wind would blow the covered table far, far away to where it looks like there’s no end to the thorny fields.

“It wasn’t easy, but we just managed to grab both boys by the hand and run back down into the dugout before the pampa wind could tear them away from us and carry them off. We were so afraid that we couldn’t catch our breath even when we were back down in the dugout. We were scared half to death.

“From that evening on, my wife took such an intense dislike to Argentina that she wanted us to return right back to Russia. But I’m a stubborn Jew, and I said, ‘I’m not going back. We left that country for good.’

“We suffered plenty on the pampa. But God helped me, and finally, I was able to build a large, new house for the whole family. Then I said to myself, ‘Now it’s time for me to get even with the pampa, which ruined my first Sukkos here in this country.’

“I put up a sukkah that no wind, no storm could budge. Now, every Sukkos when all of my children and grandchildren come together, we celebrate the holiday here with the nicest food and drink, we recite the blessing over the esrog here every day, and when it’s time to make kiddush, I tell them about that first kiddush in the sukkah that the pampa wind tore apart.

“And before I even finish telling the story about that Sukkos night when we just barely managed to save ourselves in the dugout from the pampa storm, they all cry out: ‘Zeyde, you’re a hero! A true hero! You conquered the pampa!’”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

At a time when other newsrooms are closing or cutting back, the Forward has removed its paywall and invested additional resources to report on the ground from Israel and around the U.S. on the impact of the war, rising antisemitism and polarized discourse.

Readers like you make it all possible. Support our work by becoming a Forward Member and connect with our journalism and your community.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO