Honoring The Arts

Esteemed Guest: Rocco Landesman. Image by KAREN LEON

BRAVOS TO ‘BIG APPLE’ HONOREES AT NEW YORKER FOR NEW YORK AWARDS GALA!

“This is going to be the most art-supportive administration since [Franklin] Roosevelt,” declared special guest Rocco Landesman, chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts, at the February 22 Citizens Committee for New York City black-tie New Yorker for New York Awards Gala, held at Gotham Hall. Matthew Broderick described Landesman as “a producer [who] produced ‘Angels in America,’” and with a twinkle in his eye, added, “and another show I was especially fond of, ‘The Producers.’”

Esteemed Guest: Rocco Landesman. Image by KAREN LEON

Landesman, a presidential appointee, make a proclamation about Michelle Obama’s appreciation of the importance of the arts: “The first lady gets it!…. It’s not just lip service…. For the first time, the arts have a seat at the table with the administration.” Former New York State governor Mario Cuomo presented the Schuyler and Elizabeth Chapin Award for Lifetime Contributions to the Arts to Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel, whose 40-years-long list of positions, awards and achievements include “longest-term commissioner of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission [1972–1987]” and “appointment by President Clinton to the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts. ” Her reaction to the recitation of her accomplishments to date elicited the remark, “ I still consider myself a work-in-progress.” Diamonstein-Spielvogel declared, “Ours is a life of privilege, not only of material things, but [the] privilege to serve society, to preserve the past… as the cultural connection to the future.”

Peter Peterson, president of the Peter G. Peterson Foundation, was presented with the New Yorker for New York Award by Robert Rubin, vice chairman of the Council on Foreign Relations and former U.S. Treasury secretary. Describing himself as “a son of Greek immigrants… a genuine country boy from the middle of Nebraska,” Peterson, who founded the private equity firm the Blackstone Group and is chairman emeritus of the Council on Foreign Relations, touted the virtues of “humility, courage, grace and service.” Recalling how he once imagined New York City “as [a] remote, arrogant and noninclusive elite city,” he admitted, “My experience has been the opposite of that.” Henry Cornell, board chairman of New York City’s Citizens Committee, introduced New York City Police Commissioner Raymond Kelly, “whom we owe a debt for the continuing drop in crime.” Kelly announced the presentation of a portrait by artist Cornelia Foss of Citizens Committee founding chairman (and former editor-in-chief of Newsweek Magazine) Osborn “Oz” Elliott (1924–2008), to be hung at the Citizens Committee’s. (Foss’s late husband, composer Lukas Foss, occasionally tutored Osborn, his friend, in his piano playing.)

Founded in 1975 “to encourage New Yorkers to help their city through its [then] fiscal crisis,” as the gala journal informs, “the organization now sustains… hundreds of block and neighborhood groups throughout the five boroughs, helping to make New York City’s 400 neighborhoods more beautiful and safe.” Kelly presented the Osborn Elliott Award for Community Service to Elbin Mena, a community leader in the Bronx’s Harding Park neighborhood. The evening concluded with a heart-pounding performance by the group ‘The Jersey Boys.”

“HOW DO YOU HIDE A JEWISH CHILD?” A TRIBUTE TO IRENA SENDLER AT THE POLISH CONSULATE AND A PASSING OF THE CONSULAR BATON

On February 27, the Polish Consulate in New York hosted a doubleheader. First was a special screening of Mary Skinner’s documentary “In the Name of Their Mothers,” commemorating Irena Sendler for her heroism in creating “an underground conspiracy” to spirit 2,500 children out of the Warsaw Ghetto in 1942 and 1943. The evening also marked the passing of the consular baton: It went from departing consul general Krzysztof Kasprzyk — who lamented, “It’s hard to leave America after 17 years, hard to leave New York” — to his successor, Ewa Junczyk-Ziomecka, who had met Sendler. Junczyk-Ziomecka informed that there is a proposal to designate February 15, which this year would have marked Sendler’s 100th birthday as “a day commemorating the Righteous Among Nations: Christians who saved Jews — Sendler, Jan Karski and their fellow rescuers.”

In the film, Sendler (who died May 12, 2008, at age 98), a social welfare worker who wore a Star of David upon entering the Warsaw Ghetto so as not to call attention to herself, states, “The most dangerous thing was to hide a Jewish child.” She recalled her father — a doctor who contracted typhus after treating mostly poor Jewish patients during the 1917 typhus epidemic — on his deathbed, telling her, a 7-year-old: “If you see someone drowning, you must try to rescue them, even if you cannot swim.” She added, as a personal aside, “You can leave behind a black hole or a bright light.”

Describing herself as a “superb organizer,” Sendler was able to enlist an “army” of helpers, including Zegota (Polish acronym for the Council for Aid to the Jews), that smuggled Jewish children out of the ghetto. Sometimes these children were hidden at the bottom of garbage wagons, other times they were smuggled out through Warsaw’s sewers.

Teary-eyed, she recalled one of her cellmates who had been tortured — “Her skin was no longer attached to her bones” — who refused to divulge the names of other rescuers, “even when they shot her 15-year-old daughter and 17-year-old son in front of her.” When the Polish Episcopate issued the directive to all convents and monasteries to hide Jewish children, the challenge was what to do when a child looks so Jewish that bandaging her up with only her “Jewish eyes” visible still betrays her, one heroic nun recalled. Children — some of only spoke only Yiddish — had to be drilled to say the catechism. They’d be awakened from their sleep and startled, told to recite the Pater Noster in anticipation of a surprise visit by the Germans. The film notes that all the children hidden by nuns survived!

One of Sendler’s helpers, a gutsy woman in her 90s, described her role in the rescue operation — to kill “schmalzowniks,” — blackmailers who “sniffed out” those who hid Jews and, if not paid off, betrayed them to the Nazis. “They each carried a little black book with names,” the woman said. Those names were a death sentence for both the Jews and those who hid them. “The order was to kill these rats and get the little black books,” she said. With a gleam in her eye, the woman laughed and said, “The men could not do it.” Then, aiming an imaginary pistol at eye level, she said: “I had no problem. I shot them… and got the little black books.” In the film, she is reunited with one of the now adult children she helped rescue. Although most children never found their families, a few lucky ones were reunited with one or — rarely — both parents.

“JUMP!”: A FILM ABOUT PHOTOGRAPHER PHILIPPE HALSMAN’S UNKNOWN PAST

Had I not known famed Life magazine photographer Philippe Halsman — who had been my boss at the American Society of Magazine Photographers (now known as the American Society of Media Photographers), I might not have gone to the February 16 screening of “Jump!” at the JCC in Manhattan. Directed and co-written by Joshua Sinclair, it is based on the true story of Halsman, who in 1928 stood trial for allegedly killing his father, Morduch, during a trip to the Austrian Alps. I could not believe that the gentle, sweet man I knew — Latvian-born French-speaking Halsman, a friend of Salvador Dali, had been accused of murder! Impossible! Late film star Patrick Swayze plays Halsman’s defense lawyer and, according to Sinclair, the guilty verdict no doubt was the result of “Halsman being Jewish.” Post-screening, Sinclair [ne John Luis Loffredo] told me he was born to an Italian-Jewish family and that when he was a teen, he appeared in Vittorio De Sica’s 1971 Oscar-winning film, “The Garden of the Finzi-Continis,” which portrayed a world “very much like that of my mother’s, whose father died at Auschwitz.” The film’s name is based on Halsman’s 1959 book, “Jump!” published by Life. For this book, Halsman had celebrities such as Marilyn Monroe jump in front of a blank screen. Sinclair based the film on the actual court records, to which he was given unique access.

Shot in Austria in the Tyrol, the local extras give the 1928 setting of the murder and trial a creepy texture. During the post-screening question-and-answer session, Sinclair commented, “Shooting a scene with cast members marching en masse in the town’s street in Nazi uniforms, people hung out of the windows astonished, in disbelief, at what they were seeing!” The film’s action begins in the early 1950s with a re-creation of Halsman, played by British actor Ben Silverstone, asking a Marilyn Monroe lookalike to jump again and again and again. Halsman’s philosophy, which he called “jumpology,” was that when you ask someone to jump, his or her attention is directed toward the act of jumping and the mask falls away, revealing the real person within. In flashbacks to 1928, the Halsman father-son tension is showcased and the alleged murder is murkily presented with a nod to the Japanese film “Rashomon.” Sentenced to four years of imprisonment for patricide, he was released in 1931, thanks to international publicity and to support from Albert Einstein and Thomas Mann.

During Halsman’s preliminary shoots for “Jump,” he invited me to have lunch with him on a Central Park bench not far from his 67th Street studio. He had spent the early part of the day shooting the Roland Petit Ballet Company’s prima ballerina, ** Zizi Jeanmaire**, who he said was indefatigable during repeated jumps. “She is a ballerina,” he said. Then, looking off across the lake, he mused: “You know, she was wearing a full-body leotard. When the lights hit her, she might as well have been nude.” A few weeks later, he gave me a copy of his 1953 children’s book, “Piccoli,” which he had written for his daughters. When my daughter Laura was born, Halsman and his wife, Yvonne (who did all the photographic touch-up work in their studio), sent a handmade silk and lace dress from Paris.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

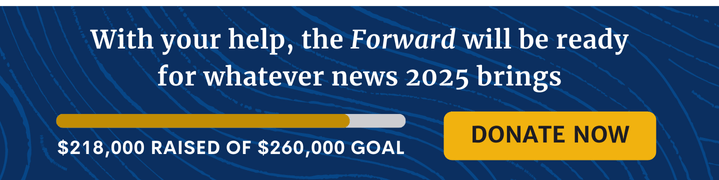

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO