Jewish Power Struggle Stirs Passion in Prague

PRAGUE — An ugly struggle for control of the Prague Jewish community ended officially late last month when the Czech Federation of Jewish Communities recognized a loose-knit opposition group as the legitimate steward of one of Europe’s oldest Jewish communities.

In fact, however, the fight goes on despite the January 20 decision. The ousted community president, Tomas Jelinek, is vowing to continue the bruising power struggle that has divided the tiny, 1,500-member community since last spring.

A district court issued an injunction in early January, giving the 250-member Open Platform the right to occupy community headquarters, but Jelinek has vowed to appeal and refuses to vacate.

The dispute is a combustible mix of religion, prestige and money. The president oversees the religious and communal affairs of a tiny community of mostly elderly Shoa survivors and 20- and 30-something post-communist converts. The community is best known for its museum and the medieval Old-New Synagogue, Europe’s oldest functioning synagogue and home of revered 16th-century sage Rabbi Judah Loew and his mythical golem. Perhaps most significant, however, the president controls the community’s extensive real estate holdings, including millions of dollars in restituted prewar properties in downtown Prague.

The fracas began last spring when Jelinek, a onetime economic adviser to former Czech president Vaclav Havel, won election with the backing of a group of mostly secular Jews. His platform called for construction of a modern senior-care facility, greater financial transparency and an easing of the strictly Orthodox religious policies of Prague’s chief rabbi, Karol Sidon.

In June, Jelinek moved to dismiss Sidon as rabbi of the Old-New Synagogue and replace him with a New York-born Lubavitch rabbi, Manis Barash, head of Prague’s Chabad center. Jelinek accused Sidon, a former dissident and playwright, of incompetence and mismanagement. Previously, Jelinek had fired the principal of the main educational facility, Lauder Javne School.

Sidon’s allies struck back at a November 7 community meeting, winning Jelinek’s ouster in a raucous scene of shouting and threats — including cries of, “You should have stayed in Terezin” — at the height of which Jelinek and his followers stalked out. Since then, the two sides have faced off in a series of legal and media battles.

Sidon still holds the position of chief rabbi of the Czech lands, and as such he had considerable influence over the January 20 ouster of Jelinek by the national federation. His support is such that in a community barely able to sustain one morning minyan outside the tourist season, Sidon’s followers — including prominent journalist Jiri Danicek and Jewish Museum head Leo Pavlat — have broken away and formed their own synagogue in protest.

Over the months the sides have aired a series of wild and mostly unsubstantiated charges in the media. Jelinek’s camp charged Sidon with misplacing Torah scrolls that never were misplaced, and accused the Lauder principal of having pornography on a computer, which turned out to be someone else’s. Jelinek’s foes accused him of passing personal information on community members to international consulting firm Ernst & Young, and of filtering his often outrageous allegations through the public relations firm Donat, whose local branch is headed by a former member of the communist-era secret police.

Jelinek said that Ernst & Young had been hired to conduct an audit of community finances, which he said had been mismanaged. His opponents accuse him of wildly overspending on the audit and on other expenses.

The accusations have been accompanied by endless legal and procedural maneuvers, including a mail-in ballot, organized by Jelinek but later ruled in violation of bylaws.

“Almost everyone who works there is either a communist or a criminal — they need to be on someone’s side” former rabbinate official Ivo Hribek said.

A new election is planned for April, and Jelinek has vowed to run again, all but guaranteeing continued acrimony.

“I won the elections last April and the old guard just can’t stand it and is trying anything possible to ruin me, which in turn is disgracing the community,” Jelinek told reporters recently. “It’s very unfortunate.”

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

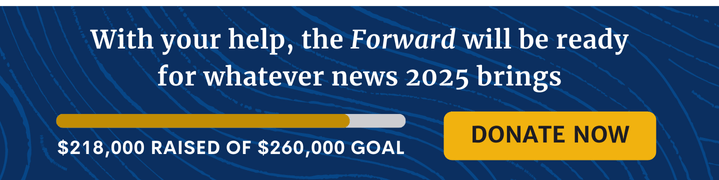

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO