Art for Art’s Sake, and More: Engaging the Collective, As Well As the Individual

Bliss

By Ronit Matalon

Metropolitan Books/Henry Holt & Co., 260 pages, $23.

* * *|

One of the challenges facing fiction writers in countries rife with political violence and conflict, such as Israel, is how to mediate tensions between the needs of the collective and those of the individual. While this tension between “engaged literature” and writing for the purposes of self-expression, or art for art’s sake, has existed since long before the emergence of modern Hebrew literature, it has been exacerbated in Israel following the second intifada and several failed peace negotiations. Yet given the embroiled nature of Israeli reality, there is surprisingly little recent fiction that directly engages the political difficulties that are most on people’s minds. Whether novels resort to descriptions of childhood or journeys elsewhere, the task of representing the complexity of Israeli present-day “reality” has become an onerous one that few have dared to confront. In a courageous departure from this trend, Ronit Matalon tackles these issues head-on in her provocative new novel, “Bliss.”

Matalon, a frequent contributor to the Israeli daily Ha’aretz and instructor of literature and creative writing at Haifa University, combines her academic knowledge and journalistic skills to write an exquisitely compelling novel. She captures the immediacy of contemporary Israeli reality by offering her readers a clear-sighted vision of the moral complexity of everyday experience confronting individuals living in such a turbulent and conflicted place. The story unfolds along two main chronological and geographic trajectories. In one, the narrator, Ofra, reflects on her personal relationships in Tel Aviv, specifically her long-term and frequently volatile friendship with her former lover, Sarah. Ofra, who is infatuated with Sarah (in fact the title of the original Hebrew version of the novel is “Sarah, Sarah”), tells the story of Sarah’s troubled family life, her marriage and ultimate separation from her husband Udi, and her affair with Marwan, a young Palestinian. Sarah ’s affair with Marwan, which disrupts both her marriage and her friendship with Ofra, becomes a way for the novel to raise a set of political questions on an interpersonal level, and their transgressive relationship turns into a catalyst for ongoing discussions between characters regarding personal and political boundaries.

The second storyline occurs outside Paris, where the narrator attends the funeral of her cousin, Michel, who has died of AIDS. The funeral, which brings together geographically distant relatives, forces the family to come to terms not only with their own grief, but also with Michel’s gay lifestyle as well as the socially taboo nature of his death.

The novel shifts between these two storylines and is ultimately held together through the larger social and political time frame that spans the outbreak of the first intifada in 1987 to the assassination of Rabin in 1995. The way in which these historical events affect the lives and thoughts of characters both inside and outside Israel becomes the subtext for Ofra’s attempt to construct a personal, moral and soul-searching reckoning of her interactions with those around her. And through Ofra’s painstaking attempts to revisit her own personal past, the narrative as a whole emerges into a larger collective account of contemporary attitudes toward a range of issues, including homophobia and tensions between different ethnic groups in Israel, as well as many of the assumptions, stereotypes and fears shaping and perpetuating the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Yet while “Bliss” may be characterized as “politically engaged,” it does not sacrifice its own beauty as a work of art. In fact, the subject of art and its relationship to politics is thematized throughout the novel: Ofra is an art historian working on her dissertation on Abstract Expressionism, and the novel’s “heroine,” Sarah, a political activist, travels several times to the occupied territories as a photographer. These characters’ artistic occupations (and preoccupations) are recurring motifs in Matalon’s earlier works. For instance, her short story entitled “Photograph” (1990) also involves a Jewish-Israeli photographer visiting the occupied territories. And her first novel, “The One Facing Us” (1995), which adopts the memoir genre to tell the story of an Egyptian-Jewish family, features a series of actual photographs that appear throughout the text. While these creative and experimental earlier works explicitly discuss the visual image and how it may be manipulated for both aesthetic and political purposes, “Bliss” incorporates such ideas in more subtle and complex ways, and on a larger, purely fictional scale. Instead of sharing actual photographs with the reader, the narrator provides highly visual descriptions of memories that are woven into mellifluous prose passages. Several of these passages contain vignettes that arrest the flow of the narrative and actually suggest a kind of “verbal painting” or photograph, adding to the novel’s graphic depiction of events.

What is perhaps most striking about this novel is that while it addresses a wide scope of social and political conflicts, it does not read as a “politically correct” manifesto, nor does it single out any one group or subculture as the sole perpetrator of intolerant acts. And, by the same token, despite the rather misleading title of the otherwise closely followed English translation — which may signal a Joseph Campbell-esque quest for self-fulfillment — the novel does not venture into the world of mythical detachment or the fantastic. Rather, the text offers a nuanced political statement about the moral challenges of living in Israel and how these challenges invade the most intimate and minute details of life, from the very language one uses to the life choices that one makes. “Bliss” successfully merges the realms of the individual and the collective, as it offers its readers an engaging political drama that is as literary as it is realistically gritty.

Beverly Bailis is a doctoral student in modern Hebrew literature at the Jewish Theological Seminary.

A message from our Publisher & CEO Rachel Fishman Feddersen

I hope you appreciated this article. Before you go, I’d like to ask you to please support the Forward’s award-winning, nonprofit journalism during this critical time.

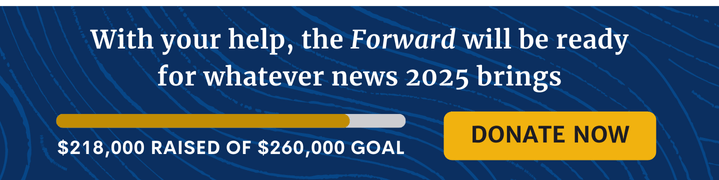

We’ve set a goal to raise $260,000 by December 31. That’s an ambitious goal, but one that will give us the resources we need to invest in the high quality news, opinion, analysis and cultural coverage that isn’t available anywhere else.

If you feel inspired to make an impact, now is the time to give something back. Join us as a member at your most generous level.

— Rachel Fishman Feddersen, Publisher and CEO